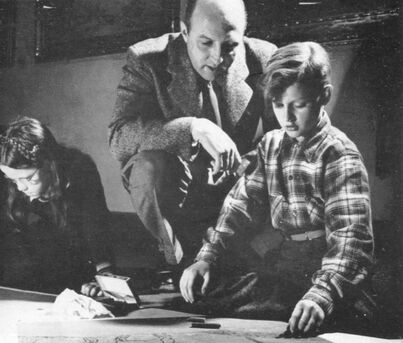

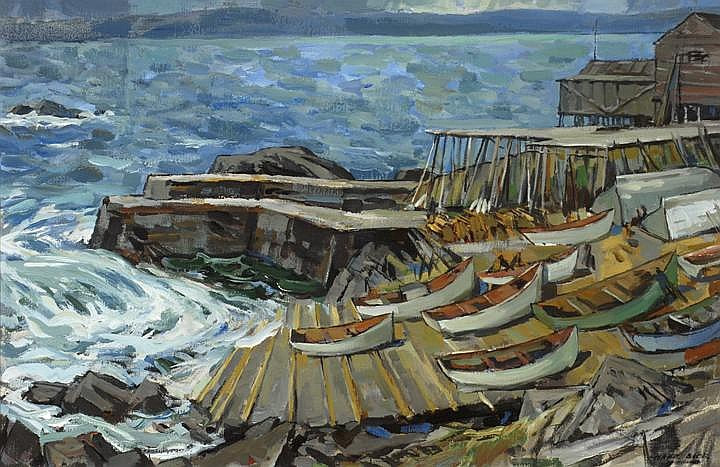

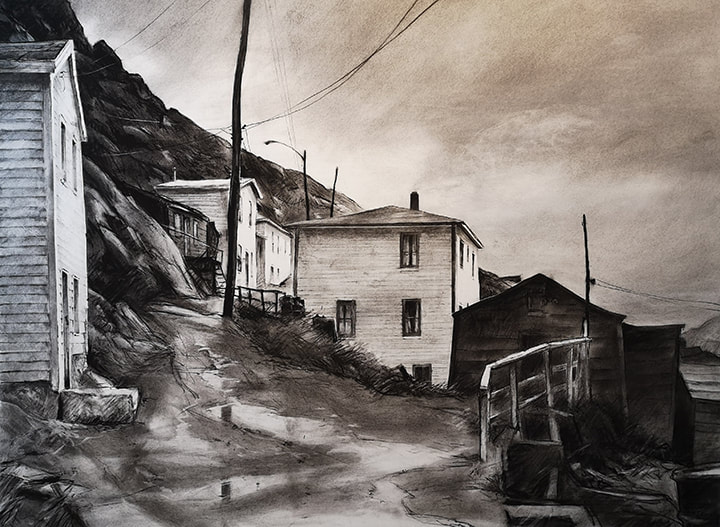

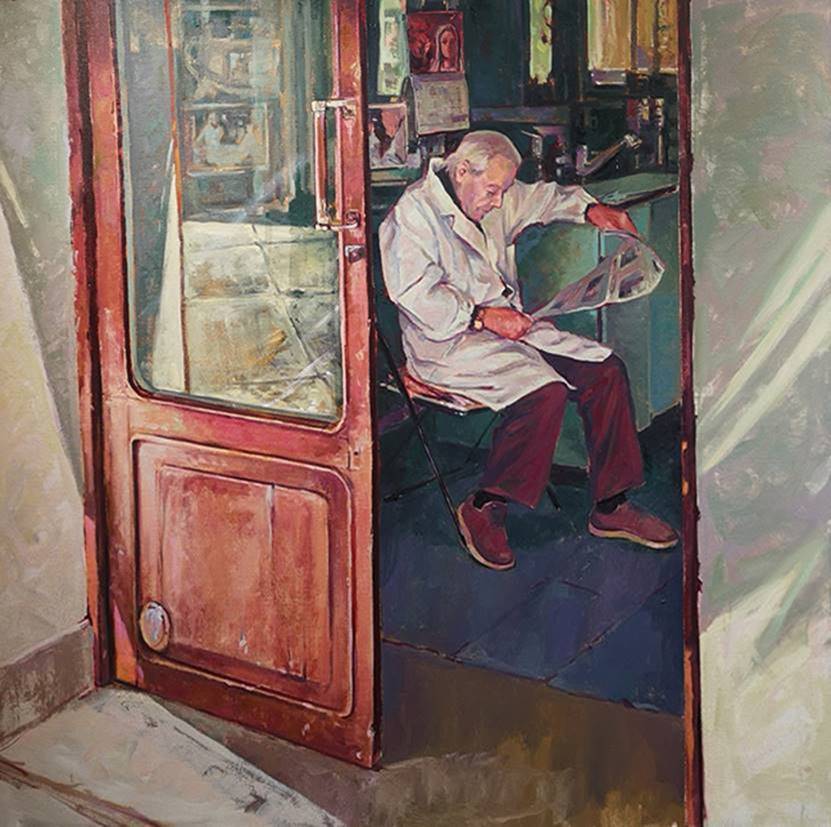

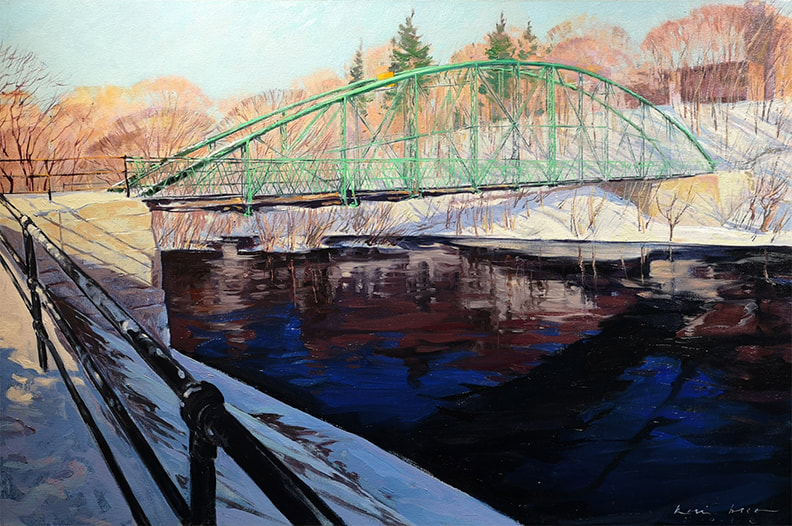

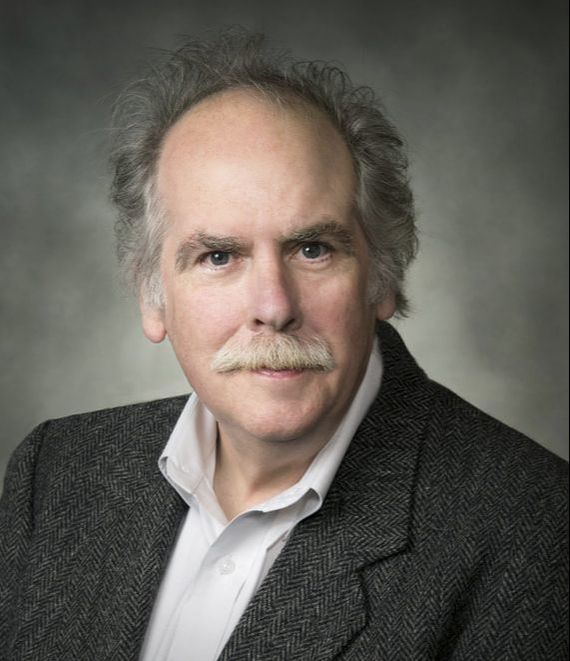

Clare and Kevin Bice at a Saturday morning art class Clare and Kevin Bice at a Saturday morning art class This week we bring you a new essay which was commissioned by the London-based online journal of visual art, Centred. You can visit them here: Like Father, Like Son | Featured Artist | Art Reviews for London and Southwestern Ontario, Canada (centred.ca) LONDON, ONTARIO – Shortly before Christmas of 2016, the Westland Gallery in Wortley Village set up a table at the opening night of a group exhibition where I could discreetly flog copies of my just published book, Three Artists: Kurelek, Chambers & Curnoe. In the milling crowd of patrons and viewers that night, I would see artist Kevin Bice and his wife Daphne from time to time but they never came near my table. The Bices are close neighbours of mine in London West and Kevin is a great mixer and natural born leader with a real gift for activating all kinds of communal enterprise. He’d drawn me into 2008’s The River Project where I wrote up the nineteen artists’ profiles for that travelling exhibition’s catalogue and he also got me to join him in a successful campaign to persuade City Hall to impose certain measures to help conserve the architectural integrity of our neighbourhood. Ideally, of course, I wanted the Bices to step on up and purchase a dozen copies of my utterly brilliant book. But if that wasn’t to be, would it have killed them to at least wave or say hello? As the end of the evening approached, I packed up my table and then went around for my own quick tour of the exhibition and that was when Daphne discreetly drew me aside to explain their standoffishness. What she lightly sketched out for me was a riveting, multi-generational story about art-making and torn loyalties in the Forest City. Two thirds of my book is devoted to the two London artists – Greg Curnoe and Jack Chambers – who are the renowned figureheads of what still is commonly regarded as the first great blossoming and never-to-be equaled heyday of London art in the 1960s. And for pretty understandable reasons, Kevin finds that too simplistic conception quietly infuriating. Not only does it overlook or shortchange the contributions of hundreds of worthwhile artists who’ve worked here in the decades preceding and following that hallowed epoch. The pivotal battle which everyone latches onto as that sublime decade’s genesis – a skirmish over a rude painted chair - took down Kevin’s father. Clare Bice (1909-76), an artist and writer and illustrator of children’s books, served from 1940-72 as the head curator of Museum London’s forerunner, The Williams Memorial Art Gallery & Museum, which was situated on the second floor of the old Central Library on Queens Ave. His association with that gallery actually preceded its 1940 opening when he curated shows in temporary spaces that were used before that grand library and museum were built with money bequeathed to the City by Elsie Perrin Williams. He did however step down from his curating post from 1942-45 for military service in World War II. “Dad was a lance corporal with a medical unit that was near but not on the front lines,” Kevin recalls. “His job was keeping accounts and shuffling papers. He had said when he volunteered that he would prefer to be in a noncombatant position because of his feelings about killing and war but he still felt it was important to go. After the war when he was still in Europe one of his publishers wrote a letter to the commander of his unit asking if he could be repatriated early because they had a big project for him illustrating children’s school books. So he was well known as an artist and an author – pretty much nationally – as far back as the ‘30s.” Kevin was born in 1946 and his only sibling, Megan, was born in 1949. Both the Bice children were powerfully influenced by their father. In addition to being a crackerjack artist in her own right, Megan served as the chief curator at the prestigious McMichael Gallery from 1987 to 2002. She died in 2019. Kevin remembers growing up in a household where there were artists coming and going all the time. “I had always lived in a household with people who made things,” he told me. “It was simply what people did. I accepted from an early age that artists didn’t all look like the stereotype you got in a bad Woody Allen movie. So my dad was the artist who went to the art gallery wearing a suit and a nice ironed shirt and a tie. He was a little overweight and he was bald so he looked kind of like a bank manager. But then I’ve got pictures of him in later years out painting with people like A.Y. Jackson and A.J. Casson and Thoreau MacDonald and here’s all these guys, all similarly shaped, all artists, but they’ve got plaid hunting jackets on and caps and big hiking boots. So it was a funny balance. I think it was one of the most valuable lessons I learned growing up - that you could move seamlessly between things. There wasn’t any particular stereotype that represented any particular job.” The artistic impulse was so naturally and deeply ingrained in them that neither Clare nor Kevin felt much need to formally study art. “Dad never really took an art degree. After he got his general B.A. at Western, Dad went to the Art Students League in New York. You’d spend a period of time there working with various artists but you didn’t have to do a four year degree or anything like that. When he was in New York, he fell in love with the ocean and went up to places like Gloucester and Boston and did a lot of paintings and drawings of ships. He fell in love with that imagery. After the war in about 1950, he started these annual trips. One year in the late spring he’d go to Newfoundland and spend a couple of weeks and the next year he’d go to Peggy’s Cove in Nova Scotia - this was before it became a tourist mecca. That was to keep up that connection with the ocean. And then in the fall he’d go up for a couple of weeks of painting in late September/early October to Algonquin Park.” And this was very much Kevin’s approach to art education as well. “To say there was a moment when I decided I was going to be in the arts . . . I don’t think I ever thought about it much. I didn’t take art in high school because there was no program. I took my degree in English because that’s what I was interested in and I didn’t take art at Western until my last year when they started up the fine art faculty. With twelve other students I took two classes a week from Tony Urquhart and Bill Dale. Bill Dale taught the whole history of art in one class – I mean over the year; I don't mean he taught it in one two-hour session. I still have the notebook from that class and it’s still something I refer to. And Tony taught one two-hour studio session per week. So when I graduated, that was it. That was my whole formal introduction to art. And at the College of Education in Toronto, I only took art as a secondary option once a week from a guy who looked like Colonel Sanders.” Another marked quality Kevin shares with his father is his community outreach. The River Project never would have happened without his leadership and this October will see the 28th installment of the Artists’ Studio Tour; an ingenious annual exhibition which he devised with Lorraine Roy in which dozens of artists all across the city sell truckloads of their work by opening up the doors of their creative sanctums to the public. The man also has an extensive history of working with local theatre companies in designing evocative and sometimes stunningly ingenious sets. Kevin and Daphne were married in the summer of 1969 after Kevin finished his stint at teachers’ college and Daphne had completed her first year as a teacher of French at Laurier. They’d known of each other all through elementary and high school. Kevin told me that he sat next to Daphne's brother in grade eight at Ryerson Public School and watched, engrossed and appalled as the boy “spent most of his year pulling wings and legs off flies and putting them in the inkwell”. “So that’s when you knew she came from good people,” I joked. He first became friends with Daphne midway through high school at Central Collegiate when they got involved with school shows and then started dating in grade twelve. “Daphne’s first three years were spent in the Sudbury area where her Dad had an insurance agency. They moved down to London when she was very young and we thought, we’ve got to go somewhere away. Somewhere new. We can’t just stay in London. We thought it would be fun to go north but it’s got to be a place of reasonable size. That gave us three options. There was Thunder Bay, Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie. Sudbury, her family had some connections up there and we thought, let’s stay away from that. Just because we wanted to be on our own. Thunder Bay was a bit far away. So we picked the Sault by default and it was the best stupid decision we ever made in our lives. “I was hired to teach English at the academic collegiate in the Sault. In those days if you had a pulse you could get a job teaching because they were desperate. The schools were exploding in population. The principal who hired Daphne to teach French at a different school in the Sault found out I had a secondary option in art and told her that he was thinking of starting an art program and wondered if I would be interested. So now all of a sudden I was going to that school and got to start an art program – there were two classes the first year – and I taught English the rest of the time. The school had never had an art program and it was a big advantage that I had no idea what you’re supposed to do in a high school art program. The Ministry guidelines at that point were completely useless. Literally from grade nine to thirteen was covered in a sixteen page booklet, half of which was pictures of smiling teachers and smiling students making art. There was no guidance at all.” I told Kevin that for a teacher with halfway decent instincts, you probably couldn’t ask for a better setup. “Absolutely,” he replied. “It was the world’s best way to start teaching and they were happy to have an art program there and the kids were itching to get taking art. It was just a lot of fun.” A few decades later, Kevin worked the same magic in London when he developed the art program at his old alma mater, Central Collegiate. (And that was a job opportunity that Kevin the four-star mixer only found out about, thanks to a casual conversation during a rehearsal of his church's choir.) It also seems to have been up at the Sault that this man who never intended to be an art teacher first realized how central art making was going to be in his life. “I remember walking home in my first year of teaching up there. It was winter and getting dark early, about five o’clock, and everybody’s curtains were still open and I was thinking, there’s something odd about these houses. And I got close to our place and I suddenly realized there were no pictures on those walls. And I thought, I guess that’s the way it is for a lot of people.” In his third year in Sault Ste. Marie Kevin had his first art exhibition in a basement room he rented at the library for five dollars a day. That might not have happened if it hadn’t been for an invitation from his father. “That spring Dad asked me if I wanted to go with him to Newfoundland on one of his annual trips. I had doodled around and pretended that I painted outdoors but I really hadn’t a lot of that experience. So I went out with him for two weeks and did a lot of painting. I soon learned that you painted quickly and you focused with him.” Kevin’s tale of their first outing, painting a scene overlooking a gorge, is punctuated with laughter as he recalls his arrogance and confidence that day, getting out of their car and heading off to find his vantage point, scouting out a level spot where he could set up his chair, and then pulling out his sketchbook and working up an elaborate series of preliminary tonal sketches and framing out his scene. “When I finally think I’ve got a pretty good start here, I decide that I’ll just go back and see how the old man is doing. So when Dad got out of the car, he just walked around to the front, plunked his seat down, pulled out his canvas and got to work. He is finished. An hour and a half and he’s done. Not only is he finished, he’s been finished for some time and he’s clearly annoyed. He never said it but the message was very clear: You learn how to paint faster or this is going to be a very long two weeks.” To his credit, Kevin did adapt his methods smartly and came back from that Newfoundland trip with a lot of on the spot sketches and worked up some larger paintings from those so that he had 74 pieces in his first exhibition and sold a third of them just like that. “From the beginning I’ve always sold pretty well,” Kevin admits. “And this last year and a half with the pandemic has been an extraordinary year for selling art. Other artists report this too. People have money from the trip they didn’t take and have been staring at that blank space on their wall and wondering what they can do with it.” It’s not hard to understand why Kevin’s work is taken up so readily. He is a superb draughtsman with a shrewd eye for framing a scene and directing the flow of our attention. He is modest about his skills as a colourist but feels that he’s been improving on that front in recent years. “I think I might be getting the hang of it,” he says. One of the qualities I respond to most strongly in Kevin’s work is the sheer sense of visual delight it conveys. At a time when so many exhibitions come with hectoring agendas or leaden subtexts that pummel one about the brow with a litany of grievances, it is such a joy to gaze upon work whose only message seems to be “Look what I saw the other day”. Kevin and Daphne returned to London in 1975 and Clare Bice died the following spring on what turned out to be his final excursion to Newfoundland. Seeing London with new eyes after six years away and then burying his father, Kevin came to a deeper understanding of what exactly had gone down ten years before with that incident about the rude painted chair. Called Seated Nude, the work by John Boyle was an actual wooden chair on which the imprint of a naked man was painted, clearly depicting his lower back on the chair’s back, and on the seat itself, his buttocks, scrotum and tip of his penis. Nancy Poole writes of the kerfuffle which Seated Nude ignited in The Art of London (1985). “It began in January, 1966 when Clare Bice gave John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Jack Chambers a three-man exhibition. On this occasion Bice refused to hang one of the [works] by Boyle, Seated Nude, because he considered it ‘unsuitable for a public gallery’ . . . ‘I did not participate in this incident,’ [Tony] Urquhart reminisced. ‘This was a ‘set up’ because when I asked John Boyle when he was sitting in my living room why he had put that ‘chair’ in the show, he replied, ‘to screw Clare Bice’. ‘I was not going to be part of that,’ Urquhart explained. ‘Clare was an honourable person. He was honest . . . old establishment . . . and I didn’t think that was cricket’.” Fifty-five years after that showdown, Clare Bice’s son makes his case for a little broadened perspective on it all. “At the time and for a few years after that, there was a bit of a thing in the paper and on the news. I didn’t think it was a terribly big deal. At that point my Dad was a well-established artist, was running a very good program at the art gallery, was well known across Canada. It only became a bigger deal for me as the legend solidified. When we came back to London, I became aware of how conservative London is. I didn’t live in a conservative atmosphere so it hadn’t occurred to me before but coming back it kind of hit you in the face how stiff and formal the city was. So with my Dad and the incident of tossing the John Boyle chair out of the exhibition, it had different stages. “First of all, the whole thing was a deliberate setup because they knew it was going to be thrown out and when they came up in all their high dudgeon, they had Lenore Crawford with them and a photographer from the Free Press. They knew this was going to create an incident. It wasn’t just a simple protest. What always bugged me about that was that any written histories of the city always seem to zero in on that incident as a way of coming up with the myth that art life in London began with that moment. And that’s absolutely wrong. “It never bothered me that Greg and the guys came in and took the work out. That’s what young artists do. It’s your job to challenge the establishment. What really pissed me off was that along the way my Dad had started a lending library of Canadian art and stocked work by a lot of London artists, all of which could be borrowed for a couple of bucks by anybody for their house or office. He’d started the Young Contemporaries Show which was specifically a showcase for artists under thirty. The Western Ontario Art Show gave a platform for anybody from an amateur to a professional.” It was also under Clare Bice's watch in 1955 that the much-missed Art Mart came into being; a wildly egalitarian exhibition that absolutely anybody could submit work to – from professionals to high school students. Community-based and almost corny, for close to thirty years the Art Mart had a vitality that no other exhibition in the London calendar could match. “To me, the energy that defined London as an art centre was best symbolized by the Art Mart,” Kevin says. “If you look at the artists who showed there, it was incredible. The idea was each artist was given eight feet of wall space and they could go floor to ceiling and they all did. They put in as many things as they could. A lot of them had bins of prints and drawing frame things in front and it had a nice church bazaar kind of atmosphere. On the Friday night when it opened, it was packed. You couldn’t move in the place. Later on the Beal students were invited; they were given a room and they could do whatever they wanted with it and sell their work. One year Jack Chambers was there and he set up a makeshift tent with sheets and he was showing 16 millimeter films. There was somebody there one year – I thought it was Greg Curnoe but I mentioned it to him years later and he said it wasn’t him – who took an 8 by 4 sheet of plywood and had done a sort of Jackson Pollickish thing on it, had a couple of sawhorses with a sabre saw and you could buy it by the square inch. You’d say, I want that bit there, and – eeehhhhhhhhhhh! - they’d zip out a chunk for you. It was that kind of thing. It was fabulous. “It goes on and on – my Dad was instrumental in developing all these different opportunities. He created a nationally known art gallery and art collection in a town that was pretty small and conservative. All those things got ignored and forgotten and that’s what drove me crazy. And it continues to drive me crazy because it’s a symbol of how London looks at all of its creative life. We tend to deliberately overlook huge aspects of it – not just visual art but everything.” I asked Kevin how his Dad coped with the trouncing. “I think it had a big effect on him. He wasn’t somebody who would rant and rave about it. He just carried on. That was his job. He had taken the work out of the exhibition, not because he thought it was a bad work. But as the person who was responsible for selecting the work to be shown in a public gallery - and there were regular visits by children all the time – he felt he had a responsibility to censor the work. And, of course, that was the point. They were putting the work in deliberately to challenge the idea of censorship. I think he was pretty conflicted about making the decision but felt nevertheless that regardless of his own feelings about it, he had to do that. “The flak really bothered him because all the things he’d done to enrich and grow the cultural scene in London were put aside by this silly incident. That and the fact that he worked for a boss who really made sure he knew that the gallery Dad managed was a department within the library rather than an equal and separate thing. That really bugged him. And I think that contributed to his heart attack which caused him to retire and probably, ultimately, four years later killed him.” There have been a couple of sweet codas to the Seated Nude debacle. Kevin treasures a letter that Free Press critic Lenore Crawford wrote to her old paper several years after her retirement rebutting a discussion then going on in its pages about how London never had an art scene before the arrival of Jack Chambers and Greg Curnoe. “History is badly served,” Crawford wrote, “when those two are listed as the beginners, or the all-important influences in making London an art centre. They received their stimulant when children in the Saturday morning art classes at the London Public Art Gallery, instituted by the late Clare Bice, who not only gave of his administrative capacity as curator but also of his knowledge and experience and above all his sympathy as a practising artist.” And in 1993 when Museum London included Seated Nude in The Heart of London Revisited exhibition, Kevin’s then-teaching colleague at Montcalm Secondary School, Cynthia Venables, went down to check out the show. “She was the only person in the gallery,” Kevin told me. “And she’s wandering around looking at it and she knows the whole story of this thing and how much it meant to us. And so she thought, “There’s nobody here. I’m going to sit in the chair.” And take a picture of it, right? So she gets up into the chair and she’s about to take the picture and she hears a voice saying, ‘You know, you really shouldn’t do that.’ She turns around and the guy says, ‘Look, don’t worry. I’m not going to tell anybody. Hi, I’m John Boyle.’ “He was living in Toronto and he’d come down to see the show. So it was just the two of them and they had a long talk and she explained why she was doing it. And he said, ‘You know, I have felt sorry about that whole incident and what it did to Clare Bice ever since then.’ Because John had just arrived in London at that time and got caught up with all the young guys and got excited about challenging the establishment and yeh, let’s do that. It was only many years later, particularly when he got involved with the McMichael Gallery and things like that, that he really became aware of the stuff that my Dad had done to develop young artists and support young artists in London and he felt terrible about the fact that this whole thing – despite the fact that that’s kind of what young artists do – took on the wrong direction.” Kevin continues to wage his campaign to wake people up to the idea that the London art scene didn’t start and then peak in the 1960s. His conversation is riddled with the names of worthy art practitioners of yore like Herb Ariss, Mackie Cryderman, Albert Templar and Eva Bradshaw. And he also keeps an eye on a bogglingly wide range of contemporary artists: “There’s some great work being produced by so-called amateur artists who are in all the art societies like the Lambeth Art Association, the Gallery Painting Group, the Brush and Palette Club. There’s hundreds of people there. I envy the passion that some of the people in say the Gallery Painting Group have; just completely dedicated to producing work. And somehow there’s no celebration of that.” A visit about five years ago to Museum London showed him there was still much work to be done in broadening Londoners’ sense of their art history: “I think it was the seventy-fifth anniversary of the gallery when they had a big exhibition supposedly looking at art in London from beginning to end. And I would say seventy five per cent of the show was the ‘60s. The first room was full of dark brown pictures and a couple of my Dad’s early ones were in there. And then there was another ten or fifteen percent for everything since the ‘60s. I remember walking around and just getting angrier and angrier at this thing which madly misrepresented our art history. I went home in a rage and I said, ‘No, no, you’re too angry, go back and have another look.’ So I went back and walked around getting even angrier and thought I’m going to do something about this. So I came home and got pencil and paper and went back for a third time and made a lot of notes and then wrote this long, long email to Brian Meehan and copied it to the head of the board of the gallery. I got a ‘thanks for your input’ letter from the head of the board and Brian invited me in for coffee and asked me if I wanted to sit on the acquisitions board. No. I hate meetings. That wasn’t the point. “I don’t know why we always seem to do this to ourselves. Sometimes I think maybe London isn’t big enough or maybe it’s become too big. I grew up in a vibrant community around the gallery and around my parents’ friends because the city at that time was a welcoming community and because I belonged to a church which was a vibrant community too. The idea of being one cog in a community I think is the most important thing for me. And I happen to think it’s an important thing for most people. We live in a time right now when there’s all these really egregious examples of people deliberately splitting communities. It wastes so much, so much energy and so many possibilities. We’re wasting so much time not creating or preventing things from being made. “I’ve been painting seriously for fifty years. Back when I was teaching people would say, ‘Oh, you’re an artist,’ and I’d say, ‘No, I’m a teacher. I’ll paint things when I get time.’ Even though I was always painting, I felt the word 'artist' had this kind of . . . like I should be wearing different clothes or something. Because I didn’t go through art school there used to be this feeling in the back of my mind that when people praised me, it really wasn’t justified. So there was that insecurity. But I’ve found, certainly in this last year, that I really don’t care anymore. I do stuff because I like doing stuff. And that’s all the justification I need.” I ask Kevin if he ever finds when he’s working away in his studio that his Dad gives him a little punch in the shoulder.

“There are a few of his brushes that I still use. I still have his easel. It’s become pretty rickety so it’s a secondary one for me. It’s never really a punch but he’s always there. He’s always part of it. It’s like, 'I’m here all the time.' Yeh. I’m always aware of him being there.”

15 Comments

Ninian Mellamphy

31/5/2021 07:34:37 am

This is Goodden on local art. I think that you will enjoy it.

Reply

Ninian Mellamphy

31/5/2021 01:57:10 pm

Dear Herman :

Reply

Daphne Bice

31/5/2021 07:35:59 am

I really enjoyed meeting this couple! Thank you for the insights!

Reply

Susan Cassan

31/5/2021 01:14:26 pm

Thank you for this insight into the London art scene. One of the great pleasures of this community is the way art, music, drama, and any form of expression flourish. Thank you for informing us on what we owe to those who may have been put into the shadows by larger personalities and a public that lacked education and discrimination. I hope this article goes into the London Room at the Central Library as it is another important piece of the story.

Reply

Mark Richardson

31/5/2021 01:15:41 pm

Herman:

Reply

Mark Richardson

31/5/2021 01:17:44 pm

I forgot to add in my previous email, we have two of Clare Bice's books for children on display in our London Room: Jory's Cove and A Dog for Davie's Hill. Thanks, again, for helping Londoners know more about their talented creator. Mark

Reply

Herman Goodden

31/5/2021 01:50:37 pm

Oh, all right then. If you insist. Seriously - yes please. I'd be honoured.

Reply

Ted Goodden

31/5/2021 01:19:25 pm

I enjoyed this article and feel it should be "read into" the history of art in London, Ontario. I went to the Saturday morning art classes (Jack Chambers was a visiting artist one memorable morning) and Clare Bice's painting of Richmond Street looking north, published in a colour booklet of Canadian cities, made a strong impression on my adolescent mind. "Winter Evening on Leslie Street" knocked my socks off. Is it for sale?

Reply

Kevin Bice

4/6/2021 11:08:02 am

I'm sorry to tell you, Ted, that the painting has been sold (to a good home)

Reply

Jennie Bice

31/5/2021 01:20:39 pm

What a wonderful article! And deeply true. I hope it makes folks dig deeper into the vast and wonderful current and historical art scene in London Ontario. I'm so very proud of all the artists I grew up knowing, but of all of them, I'm most proud of my Dad and my BoBice. Thank you for writing this.

Reply

Mora Gregg

1/6/2021 09:58:29 am

A very enjoyable article. Jim Kemp and my Dad, Joe Gregg, were deeply involved in the creation of the Art Mart. I think they were both on the board of the art gallery at the time. Penn Kemp would know. I think my Dad came up with the actual name. The painting in this post by Clare Bice appeared in a book of paintings entitled Cities of Canada: paintings from the Seagram collection.

Reply

Jim Chapman

1/6/2021 09:59:55 am

A wonderful and obviously needed addition to the history of London's art scene. My only regret is that you didn't share the "Seated Nude" painting. I have tried to find it on line to no avail.

Reply

Brian Meehan

2/6/2021 01:19:18 pm

Jim,

Reply

Cynthia Venables

1/6/2021 02:08:59 pm

A story that needed to be told in all its details. So happy to see so many of Kevin's paintings.

Reply

Andrew Kear

23/9/2021 11:49:17 pm

This is a wonderful account and, as a new Londoner, profoundly eye-opening. Thanks Herman.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed