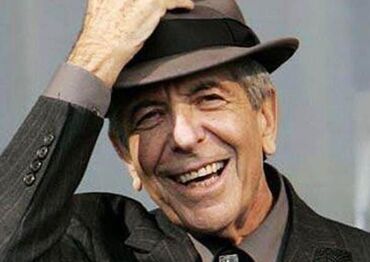

Leonard Cohen (1934 – 2016) Leonard Cohen (1934 – 2016) LONDON, ONTARIO – It was three years ago this fall (on the very eve of Donald Trump’s spectacularly upsetting electoral victory) that Leonard Cohen died in Los Angeles at the age of 82, leaving a hole in the world of music and letters that never will be filled; not even temporarily by the release next month of what will be Cohen’s 15th studio album of original material. Cohen's son and latter-day producer, Adam, has diligently gathered and dressed up some leftover tracks to compile one final album, entitled Thanks for the Dance. I confidently say that the hole never will be filled because – for me, at least – the real glory of Cohen’s music and poetry (I never made much progress with his novels) has always been a richly suggestive Zen-like emptiness that haunts the imagination. Cohen was a master of audaciously expressed intimations, impressions and allusions that you can’t quite take hold of to analyse how or why they work so brilliantly well. Originally conceiving of himself as a poet and novelist, the Montreal-born Cohen turned to music as a way of supplementing an inadequate literary income. His first musical love was Country & Western (at McGill University he fronted a trio called The Buckskin Boys), but cannily deducing that depressive Jewish cowboy music might have a fairly limited market in the era of Sgt. Pepper, kaftans and incense, he dropped the twang and refashioned his gifts in the direction of modern folk music, à la Bob Dylan.

Cohen was comparatively late to that particular party. Dylan, seven years Cohen’s junior, had a half dozen albums to his name before his inaugural platter, The Songs of Leonard Cohen, started appearing in shops in the week after Christmas of Canada’s centennial year. He was so far off the beaten path as both a composer and a singer, it’s unlikely that Cohen would have won a record contract even then if the influential Judy Collins hadn’t taken up his cause and covered five of his songs on her most recent platters, In My Life (1966) and Wildflowers (1967). For the 40th anniversary reissue of Songs, music historian Anthony DeCurtis wrote about some of the behind-the-scenes tussling which I believe helped to make that first record such a landmark: “Cohen was signed to Columbia Records by the legendary John Hammond. Hammond planned to produce the album, but was unable to complete it, and John Simon took over. Cohen and Simon fought over the string, horn, keyboard and background vocal touches that Simon thought necessary to ameliorate the effect of Cohen’s monochromatic voice. Cohen won some, though by no means all, of those battles, but, regardless, the album still rests squarely on his vocals and lyrics. The arrangements, though sometimes more elaborate than Cohen wanted them to be, are Spartan compared with the psychedelic grandeur characteristic of the period.” I don’t think any subsequent Cohen album featured arrangements so uncannily copacetic as those Simon devised for that very first outing. In the background of Sisters of Mercy, for instance, he’s woven in what sounds like a calliope, a celesta and some finger cymbals; exotic gossamer touches that I’ve missed in the numerous live renditions of that song that have been released over the succeeding half century. It certainly was idiosyncratic instrumentation but not distractingly so and I prefer it to the more generic sound of the accompaniment which turns up on so many of his later albums. Though it took another couple of years for Cohen’s audience to really find him, his appeal proved to be remarkably durable once it took hold, long outlasting such contemporary also-rans as (to name but two who are still alive and sporadically plugging away today) Joan Baez and Donovan. His support was initially strongest in Canada and Europe and what pushed him into the American market in a much bigger way about twenty years into his career was Jennifer Warnes’ release of a pitch-perfect album of Cohen covers, Famous Blue Raincoat. An accomplished singer in many different genres herself, Warnes had such a high regard for Cohen and his music that she would put her own considerable career on hold from time to time to sing back-up on his tours and records. “This is a real friend,” Cohen said of her when Famous Blue Raincoat came out in 1987. “Someone who in the face of great derision, has always supported me.” I would argue that the quality of Cohen’s melodies started to flatten out by the 1980s, much like his voice, which also used to be reedier and a little more expressive on the first half dozen albums. Melodically and musically, a song like 1992’s Closing Time, is a pretty standard issue country-swing tune. It’s the apocalyptic, darkly hilarious lyrics that knock it out of the park and make it so unforgettable. Whether he was at the top of his game as a tunesmith or not, as a lyricist Cohen had always been without peer. He should have won the Nobel Prize for Literature; not Dylan. In his case, it was no conceit to publish song lyrics in books. They really do stand up as poetry. As with Dylan, many made the mistake of wishing for stronger and more supple voices to do Cohen’s songs full justice. In fact – with very few honourable exceptions like Warnes’ tribute album and maybe Jeff Buckley’s take on Hallelujah before it got played into the ground (do you know it is one of a purported 200 different cover versions of that song?) – giving Cohen’s tunes the big voice treatment is almost never the ticket. I know some people actually seem to like k.d. lang’s leather-lunged delivery of Bird on a Wire from her album, Hymns to the 49th Parallel. But I thought it was a disastrous miscalculation that showed just how badly the ‘great voice strategy’ can misfire when the emotional timbre of a song is ignored. I’m sorry, but the bird perched on this particular wire is a frail and uncertain thing. For me, the song collapses under an utterly inappropriate burden when it sounds like it's being belted out by a great big, operatically-adept turkey vulture. There were two other factors in play that I think helped Cohen win the longevity sweepstakes. Even into his 70s the man still exuded a sexiness that made the knees of otherwise sensible women go rubbery. They would inhale a poem like The Dream from his 1978 collection Death of a Lady’s Man and go goofy: O I had such a wonderful dream, she said. I dreamed you made love to me. At last, he said to himself, the spirit Has taken up some of the heavy work. “What is the appeal?” I asked my wife one night and was put in my place with a patronizing, “If you have to ask, you’ll never know.” “But come on,” I pleaded. “Two thirds of his songs and his poems are about the impossibility of love and in the others he’s grabbing what he wants and then running away. Full of elaborate excuses, he’s the ultimate, commitment-phobic rotter.” “That’s just with other women,” my wife explained. “It would be different with me.” His other powerful and undying appeal was to particularly pretentious males in the later stages of their adolescence. In a 70th birthday essay that Robert Fulford penned for the National Post, he credited Cohen’s lasting appeal for male adolescents to his frequently explored themes of prophecy and self-pity; the over-riding sense in so many of his songs that all of us are irreparably damned. I remember seconding that insight and adding, “Don’t forget the sex, Bob. And smoking plays a big role here as well.” That first Cohen album moved through our family home like a melancholy fever lasting five or six years, occasionally lying dormant then flaring up again, eventually infecting each of the four boys in turn. It was our eldest brother Dave who first bought it/caught it, snapping up that first sombre platter shortly after its release. I didn’t know what to make of it. The front cover was a poorly focused black and white picture of Cohen taken in a Woolworth's photo booth. The back cover was its full colour opposite; a gaudy, kitschy illustration from a Mexican holy card of a naked, blue-eyed Joan of Arc staring heavenward as the flames of martyrdom consumed her. Dave was supposedly attending university that year but weeks seemed to go by when he scarcely made it onto campus for more than a few hours, if at all. The real hub of his existence that winter and spring was our living room which he’d take over every night at about midnight, and not relinquish until the first watery rays of morning light leaked out of the eastern horizon. Smoking his pipe and growing a great woolly beard, Dave would pass night after night, reading great hulking tomes by Soren Kierkegaard and Jean Paul Sartre, while playing The Songs of Leonard Cohen over and over again on the family stereo. Most nights, his cue to turn in, was hearing the morning newspaper hit the front porch. A callow puppy of fifteen that year, I found some of the tunes beguilingly sad but couldn’t begin to crack the wonder of those lyrics which were riddled with exotic terms and imagery promiscuously plundered from Judaism, Catholicism and Buddhism, and mysteriously charged with dark sexual portent. And sweeping up the jokers that he left behind you'll find he did not leave you much, not even laughter. Like any dealer he was watching for the card that is so high and wild he'll never need to deal another. He was just some Joseph looking for a manger. Five years later, my hormones having caught up with my curiosity,, I was more than ready for full immersion into Leonard-land and felt caught out one hot summer afternoon when another brother, just back from the west coast, looked in on me spinning that platter in my unlit basement room while lighting cigarettes end to end. “Woah,” said Ted in embarrassed recognition of what had apparently become a family ritual. "And what kind of summer are you having?” Obviously, this wasn’t a question that required an answer. In October of 2004, Leonard Cohen was devastated to discover that he was almost bankrupt. His long-time manager, Kelley Lynch, had wiped out his savings, his retirement accounts, his charitable trust funds, and had even sold off some of his music publishing rights. This man who had been so effortlessly able to tap into the devotion and charity of so many women, had fatally misjudged in this instance, entrusting his legacy and estate to an unworthy manager. Though he sued Lynch in 2007 for a reported nine million dollars and was legally awarded the same, he never saw the money. And so at the age of 74, an artist who could to take up to nine years between albums as he booked himself into a Buddhist monastery for three and four-year stretches of meditation and writing, suddenly had to hit the road for three grueling years as he slaved to fill those depleted coffers back up. Cohen and a crackerjack band toured everywhere – the U.S., Canada (even London, Ontario), Australia, New Zealand, Britain, Europe, Israel – typically playing Bruce Springsteen-dimensioned concerts of three hours’ duration. His best-selling Live in London concert DVD from a 2008 concert at London’s O2 Arena gives a touching portrait of a gracious artist who may have suffered a stroke of rotten luck but managed to bounce back with humility and humour as he summoned his energies one last time to showcase one of the most beguiling song catalogues of the last fifty years. His between song patter alone is worth the price of admission; two of his more delicious observations being: “The last time I played on a stage in London, I was just a starry-eyed kid of 60 with a crazy dream.” And “I’ve studied deeply in philosophies and religions but cheerfulness kept breaking through.” Circumstances or fate unquestionably forced his hand. And he certainly had to forgo the easeful sort of retirement he’d planned. But by the end of that remarkable musical revival that felt almost religious in the crowds and devotion it aroused, I can't imagine that old 'Field Commander Cohen' (as he'd once christened himself) had any regrets that this final act of his life played out the way that it did.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

10/11/2019 06:58:01 am

Hello again, I'm glad we agree about Leonard, the " Sisters of Mercy" and the "Stranger's Song have swam in the background of my consciousness since I played the album to death after receiving it the Christmas of 67 from a lady. Maybe she thought I would learn something, I still find myself singing the same joker verse you quote in quiet moments even now a lifetime later. I was puzzled how in the sisters song a Jewish boy could sum up Catholic guilt so beautifully, Later I came to understand that Catholic guilt and Jewish Angst were fashioned from the same coin. A year earlier she and I passing HMV noticed the cover of Tim Hardin's first Album prominently displayed. He's cute she said. I returned alone heard it played, was struck by the album's romanticism " Misty Roses" in particular and romantic fool I was , and still am gave it to her for her birthday. Is it only me or are the greatest love songs bittersweet, "Momentos, L'Appuntamento, Me Manchi, Les Feuilles Mortes etc.etc. Even the eternal cynic Jacques Brel had a go with "Ne Me Quite Pas". On the quiet the most beautiful women of the world considered Leonard one of the sexiest men alive. Maybe it was his understanding of the ephemeral bitter sweetness of love. Or delving into history to the "Courts of Love" of Aquitaine and Gascony and the romantic figure of the Troubadour, he had it all going for him. Congrats on another sly dig at Joan. Whatever did she do to you?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed