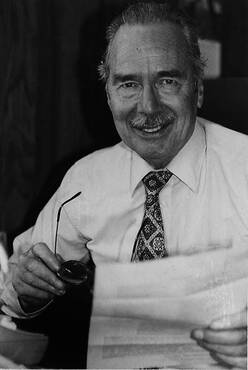

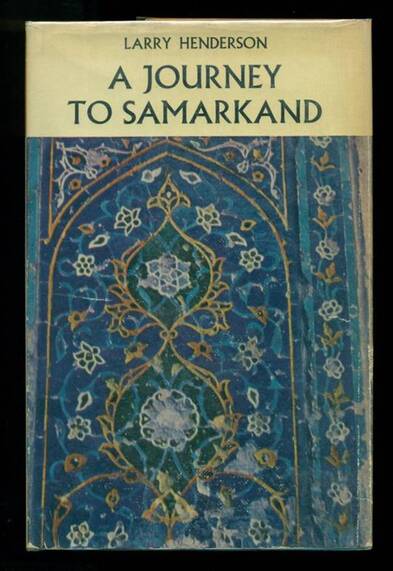

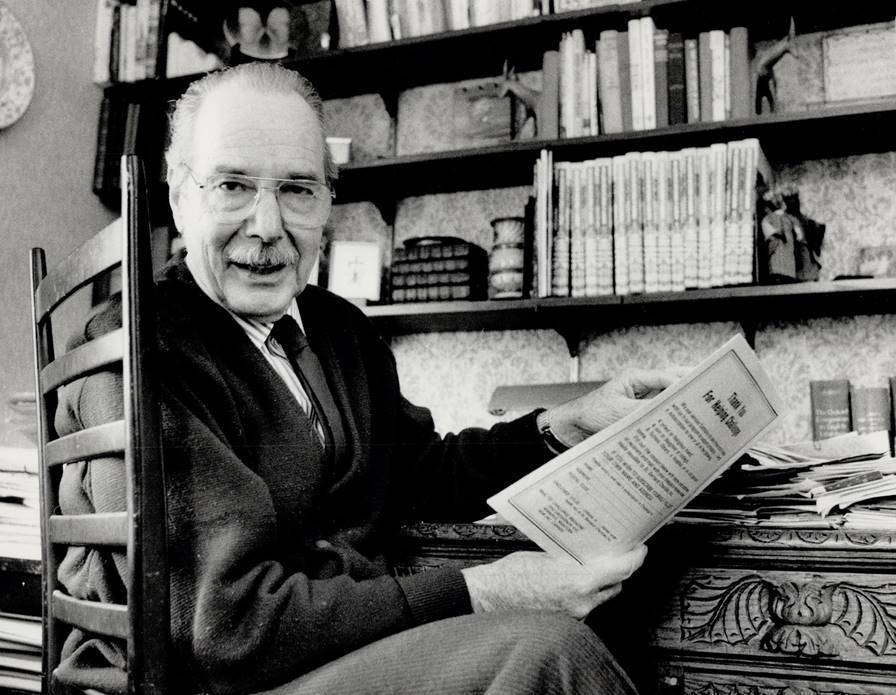

Larry Henderson (1917-2006) Larry Henderson (1917-2006) LONDON, ONTARIO – When Larry Henderson died thirteen years ago this fall, obituaries printed in newspapers from coast to coast and short clips tucked into the later portion of all the national TV news reports, focused primarily on Larry as the first full time national news anchor on CBC TV from 1954-59. During this pioneering period in electronic journalism, the CBC was the only national broadcaster around and for the better part of that decade, Larry’s was the best known face in a country full of TV sets that mostly pulled in just the one station. Larry had a sober, unflappable persona in that pre-teleprompter era when newscasters weren’t required to smile much or provide facial editorials. There were no winsome grins after the story about quintuplets, no fluttering of moist lashes to drive home the report on African famine. He could digest new and breaking information on the fly and effortlessly work it into his ongoing reports. Rare moments when he lost his cool became legendary. Many of the obituaries told of the time, after a series of technical gaffes, when he abruptly stood up from his desk and walked off the set. An older friend swears he remembers a time when Larry concluded a similarly plagued broadcast by picking up his sheaf of notes and tossing them up into the air.  Larry at the news anchor’s desk in the 1950s Larry at the news anchor’s desk in the 1950s Larry would go on to serve news anchor stints with a later national broadcaster, CTV, and other regional networks and stations. He operated his own school of broadcasting in Toronto for a while and in the 1970s Larry oversaw the setup of a national broadcasting system in Tanzania. His work as a broadcaster and reporter took him all around the world, supplying material for his book length studies from the 60s and 70s, including such titles as The Arab Middle East; Vietnam and Countries of the Mekong; and Egypt and Sudan. His most highly regarded book is A Journey to Samarkand from 1960, recounting his travels in the annexed republics of Central Asia during the height of the Cold War when precious few Westerners were allowed access to this most secretive of empires. Larry’s status as a top-flight broadcaster and print journalist obviously impressed somebody at the Soviet Embassy where Larry was handed his visa and told to “look for the best” and “avoid criminal elements”. But a Soviet visa was hardly a carte blanche even for Larry. Those few who did manage to penetrate the veil of intimidation and obfuscation that Winston Churchill dubbed the ‘Iron Curtain’ were controlled and handled virtually every step of the way by obtuse operatives from Intourist, the Soviet state travel agency for foreigners. Intourist’s control was tightest in Moscow where Larry and his entourage started their cross-continental journey and where they were put up in the Ukraine Hotel. “A monolithic monstrosity,” Larry called it, “such as Genghis Khan himself might have dreamed up under the influence of hashish. Thirty stories high, it is cleverly designed to look higher, by means of an optical-trick spire and several tons of ornamental masonry in the form of gigantic urns and palm fronds around the towers . . . Escape was impossible. There is no stairway in the Ukraine. One thousand rooms are served by elevator alone, at irregular and infrequent intervals. In the event of fire, power failure or sheer hunger, the only escape is by jumping in the Moskva River.” A staunch foe of Communism all his life, Larry lamented its continuing appeal and mystique even after the collapse of the old Soviet Union in the 1990s. What he felt the world badly needed was the post-Communist equivalent of the Nuremberg trials where the evils of this many-tentacled system could be openly tallied and condemned. During those eight or so years around the turn of the century when I knew Larry well, I was just beginning to outgrow that political naivety so typical of my coddled generation, and I blush to admit that I used to tune him out a bit when he went on one of his anti-Communist tears. He was a sensitive man and noticed my marked quietness; would say something like, “I see you can’t take this in,” and change the subject. If there was some way to play back any one of those conversations today and let it play out in unembarrassed fullness, I would dearly love to do so. I was introduced to Larry Henderson in 1996 at a time when I was desperate for media outlets. I had just walked from my job as editor of SCENE when the publisher started demanding more and shorter articles about rock music, less about all the other arts, and no discussion whatsoever on matters of faith and ethics. I was persona non grata at the London Free Press just then because of all of the years at SCENE where I regularly sniped at London’s big and cumbersome daily. Pro-life activist Alex Schadenburg (bless his woollen socks) knew the pickle I was in and set up a lunch meeting at the Marienbad Restaurant where I could meet Larry and maybe pick up a scrap or two of work. Prior to our first meeting I only knew Larry as the editor of Canada’s biggest Catholic weekly, the Catholic Register, from 1974 to 1986. When I came into the church in 1984 I actually looked forward to reading each issue. Under Larry’s very orthodox leadership, circulation had soared to never equaled heights and the Henderson years were the only period when that paper has ever operated at a profit. I came away from our first meeting with an agreement that I would start submitting articles to Larry’s final journalistic enterprise, the equally orthodox monthly, Challenge. By a quirky arrangement, Challenge was assembled in London each month but printed and distributed out of Winnipeg. My understanding with Larry quickly developed into a co-editing arrangement. Always an innovation-resistant Luddite myself, it was a real novelty for me to be the one who was leading the technological charge forward at Challenge, formatting all of our articles onto computer discs which greatly cut down on typesetting costs. The other thing I did that really impressed Larry, was I talked to the rector at St. Peter’s Cathedral and got them to take two dozen issues each month – an inroad Larry had never been able to make. Larry had become so doctrinally prickly and unyielding over the years that he’d managed to rub some church leaders the wrong way. Ignorant of any theological disputes, I just sort of blundered into these slightly charged situations and found that with a friendly overture from me, any anti-Henderson or anti-Challenge resistance was easily surmountable. And for about the next six years – until Larry stepped down as editor-in-chief and operation of the magazine passed into the hands of Ed Roche – it was my privilege and delight to work shoulder to shoulder with this man who became like a second father to me. Born in Montreal to a nominally Anglican family, Larry attended McGill University for three years on a music scholarship. He was an accomplished pianist and played all his life. Even into his 80s, he regularly organized his thoughts by first sitting down at the keyboard of his custom-built harpsichord that he kept in his book-crammed study at his last home on Cathcart Street in old South London. That was the neighbourhood I grew up in and I was amused by a geographic connection or linkage supplied by Devonshire Avenue. If you traveled east along Devonshire to its terminus and your brakes failed, you would plough through the front window of my parents home on Wortley Road. If the same fate befell you traveling to its western terminus, you'd end up in Larry's living room. At the age of 20 Larry sailed to England where he studied at the London School of Economics and did his post graduate studies in Geneva, Switzerland. Some sixty years later he told me of the day he set off to visit psychological pioneer Carl Jung at Bolingen. Finding no one home he scaled the stone wall and made his way into the great one’s study where he did nothing but breathe in the rarefied atmosphere and rearranged five coins on Jung’s mantelpiece into a more balanced formation. And then he left. Back in England for a few more years, Larry worked occasional factory jobs and tried his luck on the repertory stage, landing a starring role in Christopher Marlowe’s Faustus and playing Mercutio to Alec Guinness’ Romeo in a production of Romeo and Juliet at the Old Vic. Once the Second World War got rattling away Larry returned to Canada for his training and then served as a signal corps lieutenant in North Africa and Italy where at Christmas time of 1944, he slept one night on a tomb in the cemetery at Ravenna. Some local partisans who were also bedding down in the graveyard that night told him he was “sleeping on the bones of Dante”. He didn’t know what to make of their strange utterance until he revisited the cemetery long after the war and saw a sign next to that tomb saying that this was the site where Italian authorities had hidden the bodily remains of the author of The Divine Comedy from German marauders. This was a rich portent indeed for this man who would enter the Catholic Church 22 years later at the age of 49. Typically, Larry’s eventual conversion grew out of a reporting assignment. Calling around to Canadian leaders of various Christian denominations, he asked them all to explain how they understood that Jesus could be both true man and true God. It was only the Catholic leader, Monsignor Raymond Limoges, then Vicar General of the Ottawa archdiocese, who struck him as actually believing what he was saying and almost instantly, Larry signed on with him for instruction in the faith. Written just a few years before his conversion, again and again in A Journey to Samarkand the reader happens upon portents of the change that would soon transform Larry’s understanding of life and the world. He meets with members of an underground Baptist church and is powerfully moved by their struggle to adhere to something richer, truer and more beautiful than the Communist Party line. While his meeting with a complacent priest in a Georgian Orthodox church is a disappointment, he is deeply impressed by Sioni Cathedral and the people who worship there. “An aged man knelt beside me, praying aloud, his eyes fixed on the face of a sloe-eyed Byzantine Madonna. His prayer was a conversation, accompanied by innumerable changes of expression and intonation, in which he alone heard the reply.” Perhaps most startling is a conversation he gets into with an interpreter at the Grand Mosque at Tashkent: “The interpreter pointed out that no one who believes in God can be a member of the Communist Party. A young man of the new school, he also bogged down on several of the theological terms used in our discussion. For example, I made use of the word ‘holy’. “’What’s that – holy?’ he inquired. “I tried to explain. “’Oh, I see. You mean if you are a success at religion, you’re holy?’ “I countered that being holy was rather a condition than an achievement. ‘It means being in a state of grace,’ I concluded. “’What’s that – grace?’ he asked. “’It’s no use, you had better give it up,’ I advised him. ‘The words have passed out of your language.’” In A Journey to Samarkand’s conclusion, Larry, restless on his last night in this grim and dystopian wonderland, heads through deserted, moon-bleached streets to the cemetery on the edge of town. And there he has an epiphany forecasting the transfigurations that lay ahead, both for himself and this land he traversed half the globe to see:

“The world of men was silent and dark. It was the ghosts who were alive now. I sat upon a broken wall. At my feet lay small pieces of tile, in a heap of rubbish. I picked one up. It was only a bit of sun-baked clay, but on its surface were traced a flower and a leaf of most exquisite design, colour and beauty. That was it – beauty, a word seldom used in the Soviet world. Whatever else is to be found here – science, industry, education – there is little that is beautiful. Beauty is not in the Plan. But some day it will flower again here, as it did long ago, and will transform the barren world and the lives of men and give them meaning.” Larry possessed one of the sharpest and most broadly read minds I’ve ever had the pleasure to plunder. Once the business of our latest issue had been attended to all of our monthly editorial meetings eventually devolved into rambling chats about books and music. We’d start by talking about our most recent discoveries and before long we’d go rifling through each other’s steamer trunks, examining the books and records of our lifetimes. Considering the thirty-five year gap in our ages, we’d covered a surprising amount of the same territory. Larry was a much more methodical reader than I and subscribed to a half dozen literary reviews and read loads of classic French literature in its original tongue. While he never learned to like or use a computer, he developed a giddy sort of respect for mine when I showed him how to order up hard to find books from the international book inventories on the internet like Alibris and ABE Books. One summer evening he came over for dinner and afterwards we repaired to my study where we ordered him up a dozen different far-flung volumes in one reckless go. There were dozens of authors he either introduced me to or pressed me into finally reading, including John Lukacs, Jacques Barzun, Maurice Baring, Etienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain. He rejoiced in 1999 when Harvard University Press published the English translation of The Black Book of Communism. Larry, of course, had read the original French edition two years before. While it would never imprint itself on public consciousness as indelibly as a trial, Larry felt that this book by a committee of military and political historians at least ensured that Communism’s horrific legacy had been recorded and could be referenced by those who insisted on knowing. I took Larry as my guest to numerous classical and choral concerts in London for which I received free media passes. To sit next to Larry during a Good Friday performance of one of the great Bach passions or masses – his eyes lightly closed, head tilted slightly back, subtle emotions playing around the corners of his mouth – was an education in constructive concentration. If the music was handled at all well, the man resonated with it like a tuning fork. Walking into town together to one of these functions, I made reference to some event coming up at the big cathedral and called it ‘St. Pete’s’. Larry stopped me and for a moment I thought perhaps I’d offended him by dropping the ‘R’ but that wasn’t what had suddenly struck him. “That’s the kind of thing I mean right there,” he said to me. “I really think that’s your gift. You aren’t intimidated by a façade or a reputation. You insist on knowing things in a familiar way.” Gosh, I thought. That’s a pretty shrewd observation. In recompense for all those free concerts, Larry took me as his guest to three different plays over a 24-hour period at Niagara on the Lake’s Shaw Festival – J.B. Priestley’s Time and The Conways; Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker and Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters In Search of an Author. We both liked the first two (me particularly the Priestley; Larry particularly the Wilder) and thought the Pirandello was strained and pretentious twaddle. I don’t drive and had other commitments in town so I took the bus down to Niagara on the Saturday morning to join Larry mid-spree. Sharing a narrow, lumpy bed with him that night in the beer-soaked Angel Inn while a folk band cranked out sea shanties downstairs, I felt as if I too had slept with Dante's bones. Decidedly sleep-deprived next morning at Mass, I perked right up for our afternoon drive home across the Burlington Skyway with Larry at the wheel. In addition to Larry’s dodgy vision and the tentativeness of his command of his machine, there was something wonky in his large sedan’s alignment that caused it to constantly veer left. For a few days after our return I felt a sort of echo in my back and shoulders of the rigid tension I maintained throughout that ghastly five-hour drive. He was wisely persuaded to retire his car shortly after. And then, almost as suddenly and quietly as this wise old mentor had become such a huge force in my life, by 2002 I couldn’t help noticing that he was starting to recede on me, subtly at first, then more and more, then absolutely. Professionally and socially, Larry backed away completely over the last few years as he felt his mind was losing its customary snap and vigour. With me, at least, his sense of dignity was too great to allow himself to be seen in less than tiptop intellectual shape. I regretted that but acquiesced; feeling that to override his reticence would be cruel. There were others with whom he didn’t pull down the blinds in this way – most particularly his two sons and Father Paul Nicholson – and I envied them their access. My wife met him on a nursing home verandah the summer before he died and after reintroducing herself at some length, a sort of light went on in his face and Larry said to her twice in tones of wonder, “You know me.” Indeed we did, sir.

2 Comments

David Warren

17/2/2020 12:09:48 pm

Very fine on Larry Henderson. I knew him in Idler & early Challenge days -- from the Silver Rail when he came into Toronto -- & luckily he found me already a psychopathic anti-Communist. Also through the Muggeridges, & later Ed Roche. Like you, there are so many things I want to get back to him on; he was so far ahead of his time, one couldn't keep up. Glad to learn more of your own association.

Reply

Ian Hunter

17/2/2020 03:36:56 pm

Herman:

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed