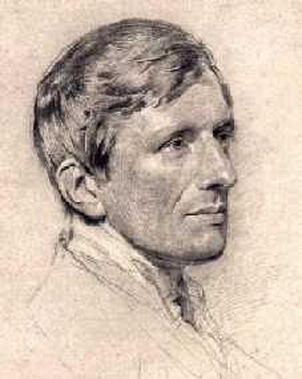

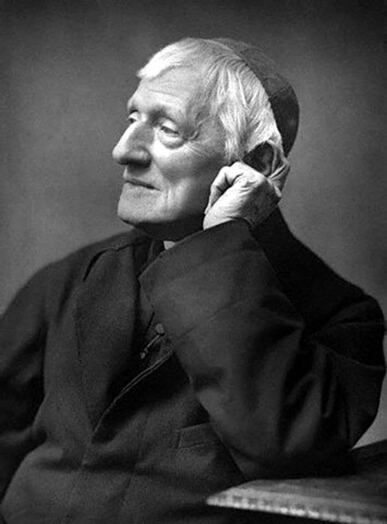

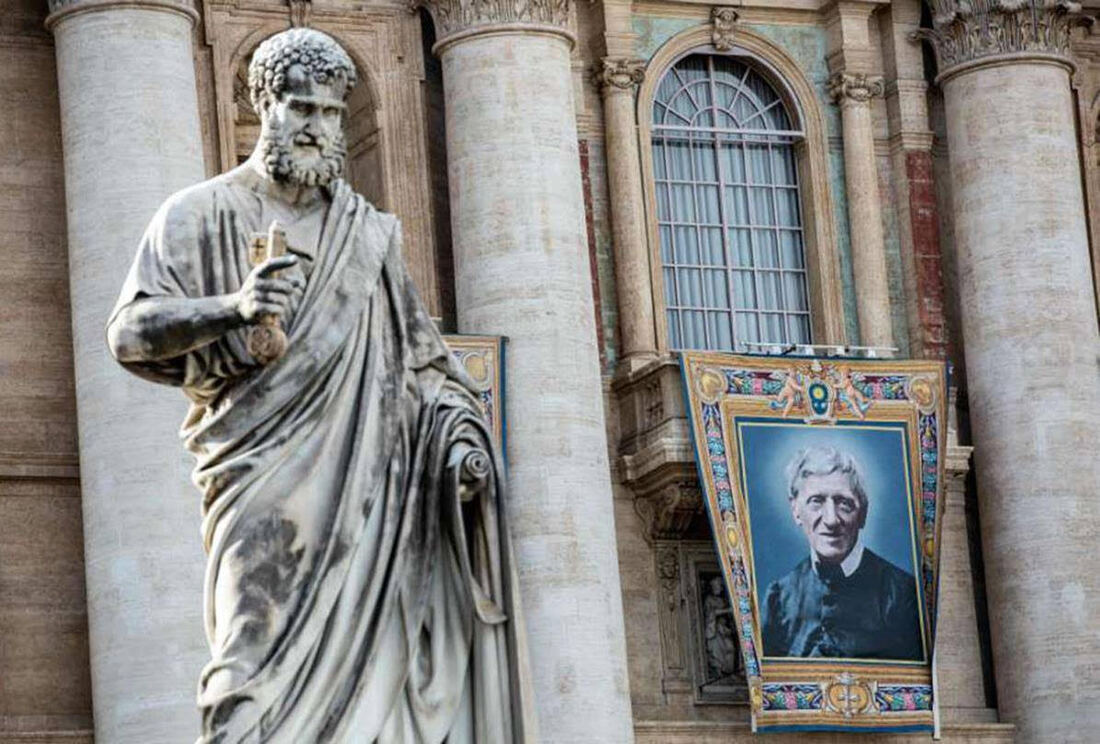

St. John Henry Newman circa 1824 St. John Henry Newman circa 1824 LONDON, ONTARIO - With a particular focus on his more devotional writings, this month our Christian men’s reading group revisited the literary remains of Cardinal John Henry Newman (1801–90) for the first time since he was elevated to sainthood in October of 2019. The foremost Newman scholar in the world today, Fr. Ian Ker (now a senior research fellow at St. Benet’s Hall, Oxford) was predicting Newman’s elevation to sainthood as early as the 1970s when he began work on his monumental biography, John Henry Newman which was first published in 1987. In the expanded edition of that work in 2009, Ker upped the ante even further and expressed his confidence that Newman will one day also be deemed a Doctor of the Church. The eight volumes of Newman's Parochial and Plain Sermons, preached from the pulpit at St. Mary’s Oxford, are the only literary product of his Anglican years which still find wide purchase today and (along with a selection of his prayers and meditations) comprise the motherlode of his devotional writings. (In comparison Newman only gathered up one volume of his Catholic sermons for publication in his lifetime.) For a long time his Anglican sermons were too little read by Catholics who regarded them as addressed to a different congregation and were similarly shunned by Anglicans who mistrusted them as incipient gleanings from a soon-to-be defector. In point of fact, what strikes one in reading those sermons today is how very un-sectarian they are. This isn't because there was anything vague or all-inclusive about his theological musings - no one struggled harder than Newman for precision and clear definition - but because his great mission in whichever church he served was to conform his mind to the surest doctrines and most sustaining traditions. It has been a novel experience for me these last couple of years and particularly this last month, to re-immerse myself in the writings of an author I’ve hardly exhausted but do know well, who has now been placed on this much higher plane by the Church we both love and which he served with such heroic dedication. It does change the reading experience His sainthood bestows a little more credence to everything he’s written, and somehow humanizes, or helps me draw closer to much earlier sanctified scribes like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. Regarded as one of the supreme prose stylists of the English language by temperaments as diverse as G.K. Chesterton and James Joyce, an edition of Newman’s collected works (not including his Diaries and Letters) runs to thirty-one volumes. Such output would be impressive enough from a man who could devote all of his energies to writing. But for most of his working life – as a clergyman with a parish to run, as a fellow and tutor of a distinguished Oxford college, as the leader of a rebellious movement that shook the Church of England to its core, as the head of a number of Catholic fraternities, as the founder and director of both a Catholic school for boys and a Catholic university, and frequently serving as a magazine editor and much sought after lecturer – Newman had to fit his own writing in on the side. As Geoffrey Tillotson writes in the preface to his 850-page compendium from 1957, Newman: Prose and Poetry (the most rounded single-volume survey of Newman’s thought and artistry that I know) “He was a priest and so looked up to as an example in point of piety, learning and morality, a preacher, an instructor, a confidant and a counsellor, and his parish – to judge by his postbag – was the whole of intellectual England. And while holding all these offices he continued to be a prolific and much read writer, unmatched for virtuosity; Polonius would have enjoyed listing the kinds – the controversial writings, tracts, poems, dialogues, essays, histories, open letters, biographies, autobiographies, lectures, treatises, novels, sermons, editorial prefacings and annotations. In a word he was one of the supreme geniuses of nineteenth century England. And a supremely literary genius.” Newman was born in the Ealing suburb of London to a quietly desperate, middle-class Anglican family. I think some biographers over-emphasize the impact that his family's financial struggles had on determining where he would put all of his attention and hope. Far more than a decision that he came to, faith seems to have been an instinct, an unshakeable disposition, that Newman was born with. Though he was a published author before he was ordained as any kind of clergyman, all of his writing was focused on religion and he knew from early on that he would be devoting his life to service in one branch of the Protestant church or another. Though celibacy was not a requirement in any Protestant church, Newman chose it for himself; electing to foreclose the pleasures of any sort of domestic life in order to give himself most completely to ministerial work. As he wrote to his sister, Jemima, at the age of 27, “What a veil and curtain this world of sense is! Beautiful, but still a veil.” In an admiring 1952 study of Newman's early life, the great Irish short story writer, Sean O'Faolain, observed, “Newman had very little intimate life apart from his family, very little at all, indeed, of what the world calls ‘life’.” It was a legitimate point. Even seventy years ago a biopic on such a rigorously ascetic life would not have been likely to pack 'em in at the downtown Bijou. But only in a more modern era of stark religious imbecility are we smug enough to denounce those who set themselves apart in this way as freaks. The tetchily unstable English biographer and novelist, A.N. Wilson (think of Michael Coren with three times the talent and capacity for work) turned against the hero of his own God-seeking youth around 1990 when his own faith was going through a bit of a spasm, writing, "I have lately re-read most of what Newman wrote, and found it on the whole a depressing experience. We associate the one-track mind either with fools or psychopaths, and Newman was neither. But when we survey his works on the library shelf, we realize that there is hardly a page in the entire oeuvre which is not concerned, obsessively so, with religion." What an absurd thing to say about a writer and a Cardinal of the Church who also happened to be a saint. As well badger Beethoven for producing nothing but music; or Van Gogh for cranking out all those bloody pictures. Prior to the 1840s, Newman was an Anglican vicar, an Oxford don and the leader of the ‘Tractarians’ or the ‘Oxford Movement’; a consortium of avid, young C of E theologians who sought to shake off what they regarded as the isolated provincialism and creedal distortions of the established English Church and situate it more clearly within a broader and unbroken tradition dating back to the time of Christ and the desert fathers. In his monograph entitled The Spirit of the Oxford Movement (1933) Catholic historian Christopher Dawson wrote that, “The Oxford Movement brought a new element into the religious life of the 19th century. It stood above all for the preservation of the spiritual identity of Christianity, and represents an attempt to restore the Catholic conception of an objective supernatural order and the Catholic idea of divine authority within the boundaries of the Established Church of Protestant England. It was by Newman that these principles were most clearly realized, and through him that they received their full intellectual formulation, but in spite of the differences of character and mentality between the leaders of the Movement, Newman, Keble, Froude and Pusey were all in complete agreement on this fundamental issue. They all stood for Authority and Tradition against Liberalism, for Supernaturalism against Rationalism and Naturalism. The fundamental note of the Oxford Movement was its anti-modernism.” The kind of watered-down liberal pieties that Newman and his cohorts sought to drive from the Anglican temple were beautifully satirized by Ronald Knox in Absolute and Abitofhell: Himself believing as believing went In that wild Heyday of th’ Establishment, When, on his throne at Lambeth, Solomon Uneasy murmur’d, ‘Something must be done.’ When suave politeness, temp’ring bigot Zeal, Corrected ‘I believe’ to ‘One does feel.’ Newman had already achieved esteem as the most eloquent and dynamic Anglican thinker of his generation by the time he undertook his deep researches into early Church history. But unknown to anyone but his closest associates, for more than a decade, Newman had been wracking his brains unto cognitive exhaustion, trying to make a case for the Church of England’s origins as anything nobler or more God-centred than a shell game which had allowed Henry the VIII to shuck his barren wife and marry his pregnant mistress. He found it equally challenging to contort the chain of apostolic succession in such a way that it could be seen to connect St. Peter to any contemporary religious leader other than the current Catholic Pope. Realizing that his thought was leading him inexorably Rome-ward, that “the modern Roman Communion was the heir and the image of the primitive Church,” Newman wrote to his sister in 1841, “I fear that I am clean dished.” Indeed this was no easy road which Newman courageously blazed. It had only been sixty years since English Catholics were allowed to openly practice their religion at all and their numbers were still miniscule. Most towns of any size had one glorious Anglican church - perchance even a cathedral which had been stolen from the Catholics and refitted and repurposed - and one shabby, near-Quonset hut of a Catholic chapel. To what use would such an impoverished and ragged remnant of a Church put a man of Newman’s rarefied gifts? In 1843 Newman resigned as Anglican Vicar of St. Mary’s, Oxford. He was also obliged to resign from his lecturing post at Oriel College, as Catholics were still barred from either attending or teaching at this school which Newman had dearly loved.His once-brilliant career was apparently ruined but in fact, it was the old status quo which now, ever-so-gradually, began to fall away. Having put behind him the energy-sapping, logic-wrenching compromises of his Anglican years, Newman was now free to commit his delicately-honed intelligence to that series of major works which comprise his lasting legacy to the world. – The Idea of a University (in which he explores what he called "the great subject of the connection of religion with literature and science" and shows that "Knowledge and Reason are sure ministers to Faith")); The Grammar of Assent (a profound exploration of the necessary psychological underpinnings of faith); Apologia Pro Vita Sua, (this history of his evolving religious opinions written to refute a charge of dishonesty leveled by the novelist Charles Kingsley was his most popular book by far); and, what many regard as his masterwork, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (in which Newman upholds a genuine continuity with tradition as the essential element in any worthwhile development of religious thought.) A full fourteen years before crossing the Tiber himself, G.K. Chesterton came up with a beautiful metaphor in a column for The Nation that illustrated Newman’s main contention in An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine: “A man who is always going back and picking to pieces his own first principles may be having an amusing time but he is not developing as Newman understood development. Newman meant that if you wanted a tree to grow you must plant it finally in some definite spot. It may be (I do not know and I do not care) that Catholic Christianity is just now passing through one of its numberless periods of undue repression and silence. But I do know this, that when the great flowers break forth again, the new epics and the new arts, they will break out on the ancient and living tree. They cannot break out upon the little shrubs that you are always pulling up by the roots to see if they are growing.” Twenty-five years before Ian Ker published his life of Newman, the popular Catholic novelist Meriol Trevor was regarded as the definitive biographer with her two volume opus, Newman, The Pillar of The Cloud and Newman, Light in Winter ( both published in 1962). While Ker's priestly and scholarly training make him an ideal guide for a tour through all of Newman's writings and books, Trevor's feminine eye gives her the advantage in filling out the contours of Newman's life and personality and relationships with his colleagues. Trevor also had the capacity to make some arrestingly intuitive insights like this one, directly linking his religious autobiography with his great Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine: "What is it [the Apologia Pro Vita Sua] but the fruitful theory of development applied to the history of one mind, as he had already applied it to the history of the collective mind of the Church? To Newman’s profoundly historical mind, to trace the development, whether of a person or of a society of persons, was to understand it in its reality, and not as an abstraction. This was why he liked to look at saints as living and growing beings, and not as specimens of perfection, minced into virtues. The Essay on Development had been read only by the most highly educated; to follow its wide deployment of ideas was beyond the general public. More people like to read the story of a person than the exposition of a theory. In telling his own story Newman was telling the religious history of England, in its contemporary setting and in relation to the whole history of Christendom; what might have been expounded in a series of learned volumes was manifested by implication in the simple tale of his own journey from the dawn of consciousness to that point of maturity when he had passed through various forms of Christianity to ‘the Church which our Lord founded on Peter. And because it was cast in the form of history and not of argument, even the most hostile were ready to read it, if only to find further material for their hostility, or from mere curiosity." So pronounced were Newman's gifts, so compelling was his personality, and so fearless was his commitment to discerning the truth regardless of where it led him, that Newman stood forth in his time as both a figurehead and a lightning rod. People had opinions about Newman. He may have been held in esteem by more people than regarded him as notorious but until quite late in his life, a nervous Church hierarchy found it prudent to post him to assignments in out-of-the-way places like Dublin and Birmingham where he'd be less likely to capture broad-based attention. In July of 1864 Newman received a craven invitation from an oily Monsignor named George Talbot, inviting him to travel out to Rome in the next Lent "to preach at my Church in the Piazza del Popolo where you would have a more educated audience of Protestants than could ever be the case in England . . . I think myself that you will derive great benefit from revisiting Rome, and again showing yourself to the Ecclesiastical Authorities who are anxious to see you." Newman's perfectly polite but lacerating rebuff to this pipsqueak is a thing of sublime beauty: "I have received your letter inviting me to preach . . . to 'an audience of Protestants more educated than could ever be the case in England.' However, Birmingham people have souls, and I have neither taste nor talent for the sort of work which you cut out for me. And I beg to decline your offer." Even before he was declared a saint, John Henry Newman had retained his status as a great figurehead into the modern era. In his life story the world has come to discern the turning of the tide at last as Roman Catholicism began to be restored to England after three hundred years of virtual banishment and exile. Newman’s anguished turning toward Rome proved to be a pivotal and inspiring first stirring in what would shortly become a tidal wave of conversions. Unthinkable in 1845, a little more than a century after Newman's conversion, there were more practicing Catholics than Anglicans in England. Less central to the reputation of this remarkably prodigious thinker and writer is the poetry that Newman wrote. It too is all religiously themed. He never made large claims for his verse but he took real care with its composition and worked at it all of his life; finding it a particularly helpful outlet during periods of uncertainty and stress. A representative anthology of Newman’s poetry easily runs to 300 pages; not much less than a collected edition of the poems of another celebrated, 19th century, English Catholic writer who is remembered for nothing but his poetry, Francis Thompson. And with the distilling passage of 130 years since Newman’s death, he is primarily remembered for two poems; a sprawling religious epic which captured and still holds the public fancy and a humbler, more intimate verse which has also managed to endure.

Newman’s epic poem, The Dream of Gerontius, written in 1865 and inspired by the Requiem Offices, depicts the journey of a soul to God at the hour of his death. It was set to music by Sir Edward Elgar in 1900 (how one wishes Newman could have heard it) and remains second only to Handel’s Messiah as the most popular English-language oratorio. A less daunting and much shorter poem, The Pillar of The Cloud, was written at sea in 1833 when Newman, still an Anglican priest, was returning from his first visit to Rome. His ship was becalmed in the Straits of Bonifacio and Newman was recovering from a dangerous bout of illness. A seed had been planted in his heart during that profoundly upsetting first encounter with Catholic culture and Newman’s poem serves as an invocation, calling on God to help him through the trials of discernment and commitment which lay ahead: Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom, Lead Thou me on! The Night is dark, and I am far from home – Lead Thou me on! Keep Thou my feet, I do not ask to see The distant scene, – one step enough for me. I was not ever thus, nor pray’d that Thou Shouldst lead me on, I loved to choose and see my path, but now Lead Thou me on! I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears, Pride ruled my will: remember not past years. So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still Will lead me on, O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till The night is gone; And with the morn those angel faces smile Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile.

6 Comments

David Warren

21/12/2021 10:41:42 am

Dynamite essay on Newman. Nothing more to say.

Reply

Rev. Bill Craven

21/12/2021 11:13:01 am

Hi Herman

Reply

Max Lucchesi

22/12/2021 10:09:18 am

Excellent piece Herman, as usual I will quibble. I would change 'tradition' to orthodoxy. Though a tradition is something one can begin today. Parts of the Syriac church, especially those in Syria and Egypt still celebrate the Mass and go about their devotions in Aramaic, the language of the Apostles. In places using the same Palestinian dialect that Christ himself spoke. Surely that is truly a spiritual tradition. Rites and devotions unchanged for over 2000 years. Even the Greek Orthodox Church's rites are unchanged almost since the founding of Constantinople. Their traditions make Anglicanism and Catholicism a little ' Johnny come lately'.

Reply

Jim Ross

23/12/2021 09:19:11 am

Max, Max... a fragile bottle of dyspepsia, knocking its own stopper off its shoulder.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

4/1/2022 10:45:12 pm

Dear Jim, from the ages of 7 till 10 years old I was at boarding school where the nuns felt it their duty to beat wickedness out of the boys and godliness into them. Then came secondary school where the strap was exchanged for the cane. A headmaster's flogging was 6 strokes on each hand and 6 on the bum. I also know first hand a mother's dream of a son's ordination. I have lived and worked in Catholic countries so know the difference between true and convenient vocations. Dyspeptic! Ross is a good Highland and Western Isles name, with a long and glorious Catholic and Jacobite history. If you are, surely you should know better.

Ginette Bisaillon

26/12/2021 10:48:27 am

Hi Herman! Nice to see you’re still around. And so am I in spite of turning 80 a week ago. Merry Christmas and happy new year!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed