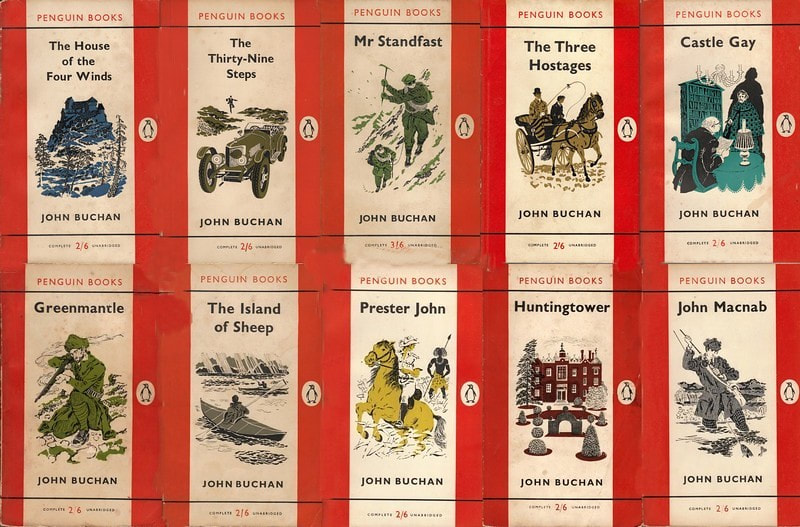

John Buchan (1875 – 1940) John Buchan (1875 – 1940) LONDON, ONTARIO – Canada is now enduring the reign of our third dubiously qualified, fiscally incontinent, female Governor-General in a row. Perhaps these appointments are consolation prizes to make up for our heartless ingratitude when the Canadian electorate turfed out our only female Prime Minister ten minutes after she was appointed to that job. If you’re keeping tabs on our recent run of affirmative-action GGs, we’ve had two ex-CBC talking heads and now we have an astronaut with the Canadian Space Agency from 2000 to 2007, Her Excellency the Right Honourable Julie Payette. Ms. Payette has been making page-two headlines this month for her allegedly abusive treatment of her staff and I was interested to read this note from a commenter at the Small Dead Animals website in response to an article they posted there about the scandal. “Took my kids on an official tour [of Rideau Hall] some years ago. We had just read The 39 Steps by John Buchan and we wanted to see how he had lived as Canada’s GG. The tour didn’t allow for that. The tour/guide was totally focused on female GGs. She didn’t have a lot of facts correct on the ladies and when I pointed the odd thing out I was followed by a manager who descended from above. We tried to linger in the portrait room to see John Buchan’s portrait and security was called but they did relent when I explained our interest. The tour guide took me aside after the tour to prog-splain her Liberal views. Was a total disappointment and I wouldn’t do an official tour again! Can’t remember if we had to pay for it.” While I don’t really give two hoots about Ms. Payette, I do carry a bit of a torch for John Buchan (1875–1940), an absolute dynamo of industry, efficiency and ingenuity who managed to rise to considerable heights on the world stage as both a writer and a statesman. This gentleman’s note to Small Dead Animals underlines one of the occupational hazards that attends anyone who wields such astonishing ambidexterity. It’s the old Jack-of-all-trades/King-of-none syndrome. If you’re too good at too much then you won’t get the credit you deserve in any of the fields you’ve mastered. As one of his more recent biographers, Andrew Lownie, writes, “Like his heroes Buchan was constantly torn between public life and private contemplation. Few men or women have equally distinguished themselves in politics and literature because essentially they require different temperaments. Buchan managed partly because he was both a man of action and thought, the scholar gypsy, the scholar adventurer, the Philosopher King.” In a writing career that spanned forty-five of Buchan’s sixty-five years, he wrote more than a hundred books that rattled off the presses at the rate of two and three a year. This productivity was particularly impressive when you take into account the ill health of a gastro-digestive nature that dogged Buchan for most of his adult life, restricting his diet to such un-zippy fare as milk and steamed fish and keeping him bed-bound for weeks at a stretch. There are photographs of him, particularly in his last couple of years, where he appears positively cadaverous. Also a distinguished journalist Buchan served terms as assistant editor of The Spectator, was a prolific war correspondent, deputy-chairman of Reuters, a publisher's assistant with the firm of Thomas Nelson, and a columnist for the Sunday Times who wrote under the pen-name of ‘Atticus’. His published works include thoroughly respectable biographies - of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, Montrose, Sir Walter Raleigh, Oliver Cromwell and Sir Walter Scott among others – as well as military histories, travelogues, essays, speeches, poetry, children’s stories and even a handbook on taxation law. In his five thrillers (or what he called ‘shockers’) featuring secret agent Richard Hannay (The Thirty-Nine Steps, Greenmantle, Mr. Standfast, The Three Hostages and Island of Sheep) Buchan pretty well invented the twentieth-century spy genre (with, as Bob McKenzie pointed out to me, a little bit of suggestive help from Erskine Childers' The Riddle of the Sands from 1903). The Thirty-Nine Steps was the first in the series and has been filmed at least four times, though never faithfully. The first version featuring Robert Donat as Hannay was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and is rightly considered a classic although Buchan’s story was radically altered in its translation to the silver screen. The later versions starring Kenneth More, Robert Powell and Rupert Penry-Jones as Hannay, played just as fast and loose with the original story but with much less distinguished results. In these novels (as also in the books of later writers Buchan inspired such as Ian Fleming and John Le Carre) the central figure acts alone to avert some desperate plot that threatens civilisation and in that dangerous process becomes both the hunter and the hunted. “You think that a wall as solid as the earth separates civilisation from barbarism,” one of his characters says in a Pre-Hannay thriller called The Power-House. “I tell you the division is a thread, a sheet of glass. A touch here, a push there, and you bring back the reign of Satan.” In his 1995 biography, John Buchan: The Presbyterian Cavalier, Andrew Lownie, expounds further on this constant theme that animated all of the Hannay stories. “Buchan was articulating a contemporary concern that was to become a predominant motif of the thriller over the next fifty years: that the old order was under threat, a threat posed as much by individuals as by nations. The certainties of an Imperial nation were being challenged and democratic government was vulnerable to the machinations of able but unprincipled humans.” In the sometimes stunningly prescient Hannay novels the threat from without is often abetted by moles who are working within the highest levels of the British establishment. In 1916’s Greenmantle the threat that looms – aided by corrupt and naive insiders – is a second rising of Islamic Jihad. The Scottish-born Buchan trained at Oxford as a barrister and was driven all his life by his Presbyterian faith (he attended three church services each Sunday in his youth) and a straight-arrow sense of service to his country that was only sharpened by his experiences running the Ministry of Information in World War I. The crescendo of his political/diplomatic career (he’d served as a colonial officer in South Africa and was also an elected MP for eight years) was achieved in 1935 when he was appointed the fifteenth Governor General of Canada – an office he filled with real distinction and zeal until his death in 1940.  Buchan made a point of journeying to every corner of the land and quickly deduced that “my chief usefulness here lies in visiting the remoter places. Canada’s real problem is how to counteract the difficulties of her enormous size and bind together her scattered population with a uniform national spirit.” At the express invitation of the Canadian Authors’ Association, it was Buchan who instituted the Governor General’s Literary Awards in 1937, lending the cachet of his office to what quickly became the most important annual art prize in Canada; though Buchan - quite Scottishly - insisted that the cash component of the prize would have to come from the Association and not his office or the Canadian taxpayer. His final novel, Sick Heart River, written when Buchan knew that he was not long for this world, is set in Canada and exudes a profound love for the country; a love that in large measure his adopted countrymen returned. Sick Heart River was the fourth in a sequence of novels (The Power-House, John Macnab, The Dancing Floor came before) built around the character of Edward Leithen, a Buchanesque lawyer of Scottish descent who serves as a Member of the British Parliament and comes over to Canada in search of a friend who’s gone missing and is faced with his own death and redemption. It is generally acknowledged that the Leithen novels are the ones into which Buchan most generously poured his own experiences and outlook. It has long been the fashion in higher academic/literary circles to sneer at Buchan as a purveyor of ‘boys’ own adventure’ type tales for not very sophisticated adults. True, his books don’t feature lots of tortured introspection and angst and you certainly couldn’t accuse him of heightened sensitivity toward non-British races or cultures. And at the other end of the intellectual spectrum, we’re now encumbered with readers who double as self-righteous statue-topplers, keen to denounce the blind spots of earlier eras while blithely overlooking those that pertain today. Such vindictive numbskulls would find Buchan perfectly intolerable if they had the patience or the curiosity to ever take up one of his books. But to approach him with a modicum of good faith and sample even a page of his lean, supple and powerfully descriptive prose is to put ‘paid’ to the charge of un-sophistication. Writing in Saturday Night magazine in 1955 when Penguin Books reissued a stylishly overhauled edition of ten of Buchan’s most popular novels, the dependably highfalutin Robertson Davies managed to strike a disdainfully withering note: “Frankly, I never liked these books very much when I first read them as a boy, and looking them over again, I like them even less. [Ha! – there it is friends; the well-upholstered Mr. Davies has just admitted that he couldn’t actually bring himself to re-read a single one of them. ‘And just how many did he manage to read as a boy?’ I’d like to know.] The characters are thin and elusive; I cannot care what happens to them because I am never permitted to know them.”  Buchan as Canadian Governor General Buchan as Canadian Governor General Yeh, yeh, yeh. We all get it. John Buchan is not operating on the same literary playing field as Anton Chekov. And just how many mysteries or thrillers did Robertson Davies ever read anyway? I mean, did he even have a taste for the stuff? In his fictional wing at least (and those are the books that have never gone out of print since they first started appearing) Buchan’s real literary colleagues are folks like Arthur Conan Doyle, H. Rider Haggard, C.S. Forrester and Agatha Christie. And amidst that crew, the man stands forth as a champion. Whenever this kind of snobby abuse starts flying around, I fondly remember a reading I hosted when good old Richard B. Wright was invited by some bluenose in the Q&A session to crap all over Arthur Haley or Danielle Steel or somebody of that ilk for selling more books than him. Bless his heart, Wright refused to play her shitty game. “I’m eternally grateful such writers exist,” he said. “And I do not begrudge them their success at all. It is the phenomenal popularity of bestsellers like those that underwrite all the other less popular stuff that publishers get to print. Like my books.” Even if those ‘shockers’ were all he wrote (and they weren’t, by a long shot), they were not written in a calculated way. Buchan was as surprised as anyone (and even a little embarrassed because he knew his mother wouldn’t quite approve) when The Thirty-Nine Steps raced to the top of the charts and stayed there. In 1931 Buchan was asked to speak at a dinner for the U.K. Prime Minister, Ramsay McDonald, and made this rather arresting observation that tells us something, I think, about his own deepest goals as both a writer and a man: “We Scots are a strange folk. We despise incompetence, but we do not greatly admire success. Our sentimental allegiance has usually been given to heroic failures, as if we had an instinct that material and worldly standards were not the true measures of value.” Incredibly, one of Buchan’s very earliest short stories, A Captain of Salvation, appeared in an 1897 edition of that celebrated journal of decadent sophistication, The Yellow Book. In his poem, The Arrest of Oscar Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel, poet laureate John Betjeman cites Buchan’s arrival on the literary scene as a sign that time has indeed run out for the brilliantly clever but fatally self-indulgent Wilde: “I want some more hock in my seltzer And Robbie, please give me your hand – Is this the end or the beginning? How can I understand? ‘So you’ve brought me the latest Yellow Book: And Buchan has got in it now: Approval of what is approved of Is as false as a well-kept vow’.” Betjeman here has drawn the line very neatly indeed. If you’re the kind of fuzzy-headed sly-boots who believes that there ever could be anything ‘false’ about a ‘well-kept vow’, then John ‘Mr. Standfast’ Buchan - throughout his life his favourite book was Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress - is probably not for you. But if you believe that concepts like honour and duty and service do not deserve to be mocked and that it can be a thrilling adventure to fight to uphold the good, then here’s your man.

4 Comments

Jim Ross

27/7/2020 11:59:52 am

Thanks, Herman. Always a sturdy surprise.

Reply

Sue Cassan

27/7/2020 12:01:45 pm

Reply

Max Lucchesi

28/7/2020 04:38:53 am

Before I was 12 years old or thereabouts I had read and loved Buchan's tales and Hannay was of course a hero of mine. We have been here before Herman. Should we deny Buchan reflected the Antisemitism and racial superiority of his time? Buchan had more to him than that. A Zionist and supporter of Women's Suffrage. As Governor General he respected the indigenous peoples of Canada and encouraged them to be part of a multicultural society. I would have preferred you compared his adventure stories to Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim 1900 and Nostromo 1904, rather than Hornblower and Tarzan, or could they bear it. Apropos, just in passing I would claim Conrad's 'The Secret Agent' published in 1907 as the first truly political spy novel rather than 'The Riddle of the Sands'. As my mother was born in Kirkcaldy, like Buchan I claim Jacobite sympathies.

Reply

Hilary Neary

27/9/2020 08:29:08 pm

Thanks for reviving another fine author, Herman. I am now reading some of Buchan's novels (most of them for the first time), having read a recent biography of him by his niece, Ursula Buchan, and recommend that work to you and your readers: Beyond the Thirty-Nine Steps (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed