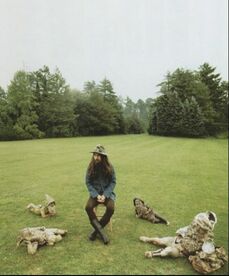

George Harrison at Friar Park George Harrison at Friar Park LONDON, ONTARIO – In early November of 1974, George Harrison launched a 26-date North American tour in support of his third solo album, Dark Horse. It was a pretty anxious and gloomy time in the life of this most circumspect of ex-Beatles. His wife Patti Boyd had recently dumped him for Eric Clapton and a bout of ill health had left the never-robust Harrison as thin as the proverbial rake and unable to shake a voice-shredding case of laryngitis that dogged him throughout his tour of Canada and the States. The ‘Dark Hoarse’ tour some wags dubbed it and as he was booked to play two concerts a night at many of the venues, his voice never had a chance to mend. This ramshackle set of concerts in which he split the bill with Ravi Shankar (an undeniably brilliant musician whose sets were frankly baffling and / or trying for a large part of the audience who just weren’t that into him) garnered close scrutiny as the first North American tour by a Beatle since that world-changing band had broken up. Expectations were impossibly high and the disappointment was profound. ‘Transcendental Mediocrity’ was the verdict of Rolling Stone magazine; a stinging putdown that kept him off the concert stage for years.

When Harrison finally got back to his palatial Friar Park mansion at Henley on the Thames late one night in early 1975, you might expect that he’d race up the stairs to pour himself a hot bath, then dive into bed for two days and not come out of his house again until the spring. But in fact it took a few hours until he could bring himself to go inside. “When I got off the plane and back home, I went into the garden and I was so relieved,” he told his press agent and confidante, Derek Taylor. “I couldn’t even go into the house.” I felt a deep surge of fondness when I first read about Harrison’s domiciliary standoff because, in one way and another, it’s a behavioural quirk I also have been prone to all my life. The time that was most like Harrison’s, was returning from a trip to Britain and Italy in the late autumn of 2005. Kirtley was out on the west coast attending to the recent arrival of our first grandchild and not wanting to impose on any of our kids still at home to come and fetch me at two a.m., I hauled my luggage the twelve or so blocks from the Robert Q depot and then stood mesmerised outside our sleeping house for about another hour before heading inside. Quite often when I’m in the homeward stretch of any big journey – sorry that it’s about to end but not sorry to be returning – I remember an utterly charming comment my brother Bob made when we were talking late one night in the basement of our family home shortly after he’d returned from his first trip to Europe in his early 20s: “Isn’t it amazing that you can wander to the other side of the planet and still make your way back to the exact same spot that you set out from? Wasn’t it ingenious of human beings to figure that out?” Even at the time my 18 year-old self knew that he was expressing gratitude for the human faculty of attachment to place, at least as much as his amazement at human ingenuity. But I don’t have to cross an ocean or even leave the city to have one of my ‘stand-outside-and-stare-at-my-own-house-in-wondrous-disbelief’ moments. Sometimes on evenings when I’ve walked the dog or fetched some milk, I get back to this place which I ordinarily take for granted, and am somehow compelled on this particular night to stop in my tracks and take a few minutes to . . . can you believe it? . . . behold it all in a state of gobsmacked wonder. This home where we’ve lived for almost 37 years is no Friar Park mansion but a rather humble riverside cottage with precious few points of interest to command the attention of architectural tourists. I can hardly say it’s news to me that this is where I live but on those nights of loitering outside my own windows with intent, I undergo epiphanies where this well-known fact somehow startles me with the force of fresh realization. In some ways it reminds me of a reconceptualising trick I used to play on myself in the 1950s. As a kid who spent a lot of his leisure hours stretched out on the floor, I would occasionally lie there staring up at the ceiling and play a little game of shifted perspective. Pretending that the ceiling was actually the floor, I would try to imagine what it would be like to walk that way from room to room. And apart from the requirement to somehow scramble over these strange two-foot plaster partitions that blocked the base of every doorway and to take care not to kick the glowing toadstool light fixtures stupidly installed in the centre of every room’s floor – what were the builders thinking? – these reveries worked a similar magic of infusing a beloved and oh-so- familiar place with an almost intoxicating freshness. The Remembrance Day before last, Connie Weir and the South Collegiate Alumni Association brought out a commemorative book called Knowing No Defeat, featuring two-page write-ups of the 57 men who had attended South and gave their lives in World War II. The book grew out of a history project which now-retired teacher, Pete Telford, had assigned to his Canadian History students in the mid-90s to go out into the neighbourhood and dig through military and newspaper records to find out everything they could about the men who were pictured and named in the memorial showcase in my old alma mater’s front hall. Realizing that time was running out for gathering salient information about these men, Weir, Telford and Jerry Selk (who succeeded Telford as a history teacher and further developed the research he’d set in motion) pulled all the material into this book. The front cover is graced with my brother Ted’s stained glass panel depicting the Boer War Memorial in Victoria Park. Included with each of the 57 biographies are photographs of the men, the medals they won, the insignia they wore, the airplanes they flew, the ships they sailed in, their gravesites, old yearbook pictures of clubs they were in or teams they were on, and – in every case but nine – pictures of the homes they lived in. Perhaps if you didn’t go to South and walk that neighbourhood’s streets for four or five of your most impressionable years, those pictures of mostly unremarkable houses wouldn’t seem so powerfully intimate and telling, so beautiful and pathetic; wouldn’t pull you in so effectively to an aching contemplation of precious lives – in many ways, so much like your own – that were selflessly and gallantly offered up for the good of others. Sometimes it is helpful in a clarifying way to objectify the subjective. When we’ve been hit by a big change, absorbed a powerful new experience, or just get too caught up in the day to day rush and swirl of life, we have to step outside ourselves to fully comprehend what we’re up to, to appreciate what we have and what we are, or to properly savour the improbable miracle that we’re here at all. One of the surest and simplest ways I know of to accomplish this, is to walk ten or twenty paces outside your own front door and turn around and look. Knowing No Defeat, published by the South Collegiate Alumni Association is available at Tuckey's Home Hardware in the Wortley Village and at Attic Books, London Ontario.

3 Comments

Jim Ross

20/1/2019 06:51:56 pm

Beautiful, Herman. I stopped breathing once or twice.

Reply

Sue Cassan

21/1/2019 08:32:41 am

This is an extraordinarily thoughtful piece. The headlong rush of the day to day occupies the foreground of our lives. We miss the context. We miss the fact that like those war heroes, if more humbly, we too form part of the tapestry that makes up the life of this city. I have had the opportunity to stand outside the houses where I lived as a child. They are so distant from London in time and place, existing in a swirl of memories. It would be good to stand back from my own home where I live right now to catch a glimpse of that life I’m having that is passing by so quickly and one day will be no more. We so seldom appreciate the wonder “that we’re here at all”.

Reply

Bro Bob

24/1/2019 09:41:51 am

A engaging reflective article Herman.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed