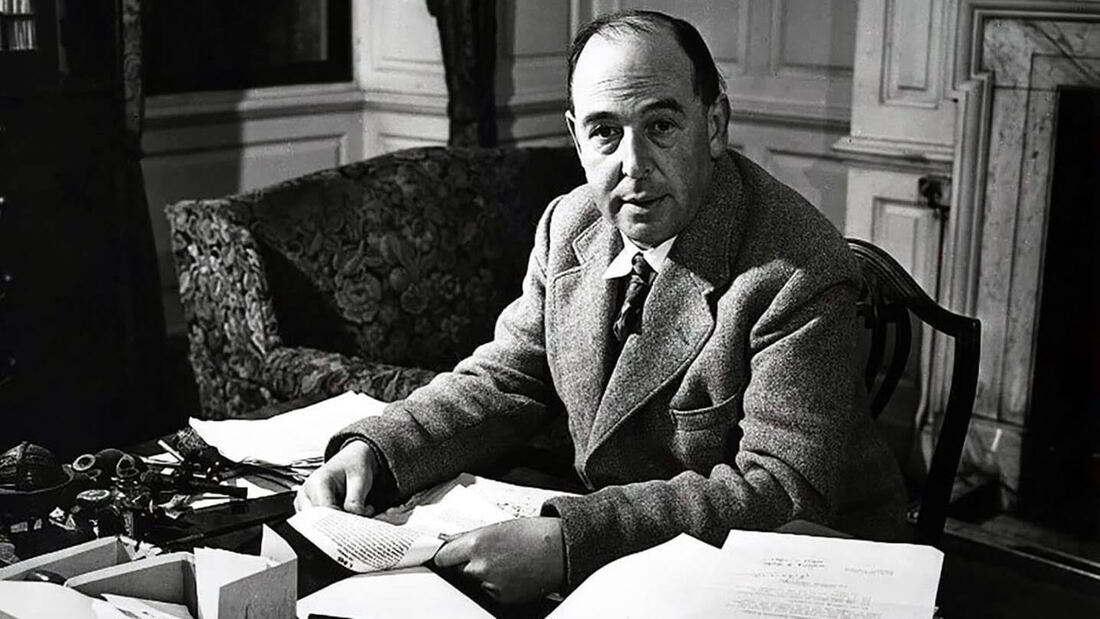

LONDON, ONTARIO – This month the Wrinklings, for the second time in their twenty-seven years, devoted an evening’s discussion to one of the shortest (sixty-four pages) and lesser known titles in the gem-packed canon of British author, Oxford literary scholar and Christian apologist, C.S. Lewis (1898–1963). The book we explored once again was The Abolition of Man: Reflections on Education with Special Reference to the Teaching of English in the Upper Forms of Schools (1943). That main title may seem to set off an alarm which the subtitle then tries to muffle. But the seasoned Lewis reader confidently proceeds, knowing that if any writer can make the latter fully redeem the former, it is he. Inspired and inspiring teacher that he was, Lewis’ uncanny facility for revelatory expression enabled him to develop any insight – no matter how abstruse or insignificant it might appear at first glance – into compelling expositions that are thrilling to read. Considering my propensity for turning out essays on favourite writers (and considering that our Christian men’s book club is named in winking tribute to The Inklings, the reading group that Lewis started up with J.R.R. Tolkien and several other Oxford profs and dons) it might seem odd that I’ve never written about Lewis at any length. A lot of what drives me to write about the authors I select, is a desire to cast a little light on worthy souls who’ve been forgotten altogether or aren’t receiving the respect they deserve. And that simply is not a service that C.S. Lewis requires. For the last twenty years of his life and the six decades since his death, Lewis has been the single biggest name in English apologetic writing and has been the subject of more biographies and studies than any other modern Christian thinker. Though I’ve read a lot of Lewis – at least half of his massive output, I’d say, including all of his fiction and apologetics and his letters and memoirs – I’m not so conversant with his more scholarly writing; most of which is focused on English writers and poets of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Yes, I’ve read most of George Herbert’s not terribly onerous oeuvre and a fair whack of Izaak Walton, John Donne and Thomas Browne. And I hope to read a good swath of John Milton and maybe even some Thomas Traherne before I die. But Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser . . . well, barring some sort of consciousness-shifting head injury, probably not in this lifetime. The persuasive authority that Lewis brought to all of his writing was made possible by his immense and detailed grounding in the work of all these writers and hundreds of others, both ancient and modern. He wore his authority engagingly and lightly. Though he could dispense insights and judgements with the apparent ease of an avid conversationalist who can’t wait to tell you his news, he was never, as they say, offering anything ‘off the top of his head’. Unlike so many scholars, Lewis never found himself encumbered by all of the knowledge inside his cranium. He no sooner finished one project then he took up the next one and, just to exercise a different set of literary muscles, would occasionally venture into unfamiliar and sometimes virulently disrespected fields where he’d never gone before – like children’s literature, fantasy, the epistolary novel or science fiction – and create something utterly fresh and unmistakably his own. Lewis’ biggest readership has always been found among Christians and religious seekers who, it must be admitted, sometimes aren’t the most adventurous readers. When a Lewis title or dust-jacket blurb does not promise a forthright exposition of the faith within, then that book’s readership will be fractionalized. This is a shame on at least two fronts. It is salutary for any reader to occasionally roam beyond the border of their specialty and take in new vistas. And with a mind so steeped in Christian understanding as Lewis’, it was inevitable that some implicitly Christian insights would be subtly woven through anything he wrote. That is certainly the case with The Abolition of Man. While he avoids a specifically Christian underpinning for his thesis here, Lewis does invoke the idea of a universal ‘natural law’ or’ Tao’ that is inborn in every human heart. Frequently, this instinctive sense of right and wrong will later serve as an interior nest for a more formally articulated religious faith. Similarly, the least-read of Lewis’ fictional works is the superb ‘Til We Have Faces which draws its inspiration from pre-Christian mythologies; most particularly the story of Cupid and Psyche. And again, his deeply reimagined telling of that tale is hardly at odds with a Christian understanding of human psychology; he just doesn’t highlight it with one of those yellow felt-tipped pens. Part of the reason why Lewis was able to attract such a large Christian readership is that although he attended the Church of England throughout his Christian life, he never wrote denominationally. His single best-selling apologetic work, Mere Christianity, takes great care “to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times.” And he makes it clear in one of that book’s earlier pages that, “You will not learn from me whether you ought to become an Anglican, a Methodist, a Presbyterian, or a Roman Catholic.” Though his appeal may be ecumenically broad in that he doesn’t bother exploring the niceties of, say, predestination or purgatory, Lewis never gets wooly about the big stuff and, as far as he goes, remains utterly orthodox. So it’s been interesting to watch over the last half century that, as the C of E has lost adherents by repeatedly trimming its sails to accommodate just about any dubious wind that the zeitgeist sets blowing, Lewis’ appeal to more traditional believers has only grown. The Wrinklings’ return visit to what feels right now like my single favourite of all Lewis’ texts – which is to say that if I re-read his Screwtape Letters next week, that might move back up to the top of the list – was prompted by the recent publication of After Humanity. This exhaustive study of The Abolition of Man (four times longer than the original document) is published by the academic wing of the Catholic publishing house, Word on Fire, and is written by a Catholic priest and Oxford Research Fellow, Michael Ward, who seems to have inherited the mantle of ‘Keeper of the Lewis Flame’ from Walter Hooper (1931-2020) who died of COVID at the age of eighty-nine. The American-born Hooper (who converted to Catholicism in his late fifties and believes Lewis would have been impelled to do the same had he lived much longer) served as Lewis’ personal secretary in the last year of the great one’s life and then devoted his next six decades to extending Lewis’ already considerable influence even further. Hooper co-wrote an early biography with Roger Lancelyn Green, latterly compiled a thousand-page Companion & Guide to Lewis’ entire literary corpus and pulled together more than thirty best-selling books from Lewis’ scattered literary and religious essays, university lectures, juvenilia, early fiction, poetry, diaries and letters. I believe Hooper’s single greatest accomplishment is his compilation of a staggering four thousand pages worth of Lewis’ letters that appeared in three fat volumes between 2004 and 2007; a set which comprises one of the great epistolary collections of the twentieth century. Father Ward’s approach can be a little more esoteric than Hooper’s. His earlier Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis was a little too cryptic for a lot of Lewis fans to stick with to the end. But he’s on far more accessible terrain with After Humanity as he traces the development of Lewis’ philosophy of education and fleshes out, sometimes line by line, the many historic, cultural and literary references and allusions that are scattered throughout Lewis’ book. The Abolition of Man grew out of three wartime lectures which he delivered on three consecutive nights at Durham University in February of 1943. In these remarkably prescient lectures Lewis dissected a just-emerging educational practice which, so far as he could discern, seemed to be designed for the wicked purpose of blunting a young student’s capacity to either grasp or speak the truth as he was equipped to know it. Lewis primarily focused on two new textbooks that were being used in English schools which he found particularly corrosive, The Control of Language (1940) by Alex King and Martin Ketley and The Reading and Writing of English (1936) by E.G. Biaginni. Not wanting to make his contempt for these books seem like some personal vendetta against their authors – and not wanting to inadvertently advertise the books in any way – he simply called the first one (and the worst one) The Green Book and referred to its authors as Gaius and Titius.

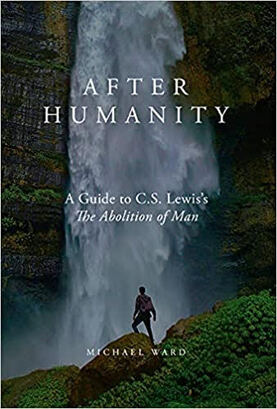

The first lecture in Lewis’ book is entitled, Men without Chests; an allusion which he fleshes out here: “Without the aid of trained emotions the intellect is powerless against the animal organism . . . In battle it is not syllogisms that will keep the reluctant nerves and muscles to their post in the third hour of the bombardment. The crudest sentimentalism (such as Gaius and Titius would wince at) about a flag or a country or a regiment will be of more use. We were told it all long ago by Plato. As the king governs by his executive, so Reason in man must rule the mere appetites by means of the ‘spirited element’. The head rules the belly through the chest – the seat, as Alanus tells us, of magnanimity, of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments. The Chest – Magnanimity – Sentiment – these are the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral man and visceral man. It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal. The operation of The Green Book and its kind is to produce what may be called Men without Chests.” The front cover of Father Ward’s book features a photograph by Didin Emelu of a man silhouetted against the thunderous blur of an immense Indonesian waterfall. ‘A lovely picture,’ you might think. ‘But what’s it got to do with teaching English?’ That mystery is cleared up on the very first page of The Abolition of Man. “In their second chapter,” Lewis writes, “Gaius and Titius quote the well-known story of Coleridge at the waterfall. You remember that there were two tourists present: that one called it ‘sublime’ and the other ‘pretty’: and that Coleridge mentally endorsed the first judgement and rejected the second with disgust. Gaius and Titius comment as follows: ‘When the man said That is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall . . . Actually . . . he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word ‘Sublime’, or shortly, I have sublime feelings’ . . . But the authors are not yet finished. They add: ‘This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.’” Lewis makes clear the damage which he believes is committed against a student when he is not so subtly discouraged from allowing any intangible hooey about valour or loyalty or honour or tradition to colour his appreciation of a poem or a work of prose or a waterfall or a sunset: “The schoolboy who reads this passage in The Green Book will believe two propositions: firstly, that all sentences containing a predicate of value are statements about the emotional state of the speaker, and secondly, that all such statements are unimportant . . . Where the old [education] initiated, the new merely ‘conditions’. The old dealt with its pupils as old birds deal with young birds when they teach them to fly; the new deals with them more as the poultry-keeper deals with young birds – making them thus or thus for purposes of which the birds know nothing. In a word, the old was a kind of propagation – men transmitting manhood to men; the new is merely propaganda.” Only five years after Lewis wrote The Abolition of Man, George Orwell published his famous dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, in which a totalitarian government breaks the will of its citizens by imposing a similar strategy of linguistic manipulation called ‘Newspeak’. In Orwell’s benighted society, the meaning of words is arbitrarily changed and disfavored words are ‘disappeared’ and driven out of circulation altogether by government apparatchiks. As the head functionary in charge of revising the dictionary explains to an underling: “Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it . . . The Revolution will be complete when the language is perfect.” What jumped out at me during this most recent reading was how much the sort of linguistic tyranny that Lewis and Orwell were alerting us to eighty years ago, resembles that life-choking weed of mind and speech control that we all know today as ‘wokeism’ or ‘political correctness’. Of course, our school systems are rotten with it today but, even as truncated as my education was - getting out after grade eleven - I remember experiencing some of it back in high school in the late 60’s when I was left quietly simmering as teachers denounced certain students’ observations as worthless ‘value judgements’. Today the mind-conditioning has gotten so bad, even in elementary schools, that I don’t think I would entrust my kids to the public or Catholic system. One of Lewis’ big concerns in 1943 was that this push to cleanse students of what reformers saw as outmoded sentiment, would ultimately unfit citizens for carrying out functions that society as a whole still had occasion to value: “And all the time – such is the tragi-comedy of our situation – we continue to clamour for those very qualities we are rendering impossible. You can hardly open a periodical without coming across the statement that what our civilization needs is more ‘drive’, or dynamism, or self-sacrifice, or ‘creativity’. In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.” What makes our current historical moment so desolating to behold, is that not only are our ideologically addled overlords no longer clamouring for dynamism, creativity, honour or fecundity – frankly, they find all that stuff toxic and yucky - they seem to be doing everything in their power to stamp out the possibility of any sort of human flourishing at all.

5 Comments

SUE CASSAN

16/1/2023 07:50:33 am

Scarcely a day goes by that does not provide terrifying examples of Orwell’s 1984 coming to life. When Jordan Peterson sounded the alarm about compelled speech, chattering classes laughed at him, saying his fears of legal repercussions were nonsense. And here we are. Peterson fighting the governing body of his profession, because he can afford to. We know that other psychologists who have invested years of effort and money into being able to practice, are muzzled. As are teachers, nurses, clergy, doctors, journalists, police, and anyone else with a governing body. We don’t dare define a woman, and a child with a disordered perception of his or her body cannot even be offered an alternative idea of what might be wrong by a physician. I am old enough to remember thinking politically correct speech was hyper politeness, silly but harmless. Between what teachers cannot say, and what they must say students are deprived of both chests and brains. Other than the brave efforts of Austen University, and Ralston University in Atlanta, there seems to be nowhere for a student to go for an education. The molding of the population into compliance is almost complete.

Reply

Ian Hunter

16/1/2023 09:19:39 am

Excellent piece, Herman. Is it mere coincidence, or something more, that as the abolition of "man" (i.e, human beings, as Lewis meant) continues apace - "men" ("those who cannot bear children", as a Catholic publication recently defined us) have been largely eradicated from public discourse?

Reply

Barry Allan Wells

16/1/2023 04:18:18 pm

In retrospect, perhaps it was a mistake to give women the right to vote in government elections. Now the human race is no longer called "mankind."

Reply

Mark Richardson

16/1/2023 11:49:58 am

Thanks for another great column, Herman. I didn't know about this new book by Michael Ward, but thanks to you I have requested the Central library get a copy. Cheers.

Reply

Bill Myles

18/1/2023 09:27:51 am

I think Sue said pretty much what I felt like expressing (I should stop now). I should also "regret" having read 1984, Brave New World, Farenheit 451 and The Machine Stops (short story) in high-school as they make me afraid of what I see happening today. I assume they all disappeared from the curiculum after I disappeared from South Collegiate. When I get my time machine, I´m heading back to somewhere between high school and the invention of the internet. (150yrs. gets us back to outdoor toilets and no electricity). I have nefarious plans to "Terminate" a few things (like the internet). I write this on my way back to the furniture.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed