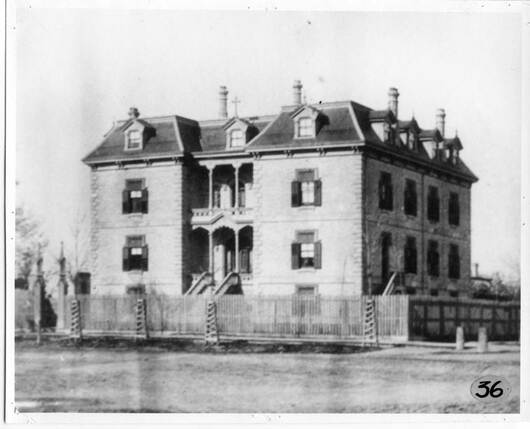

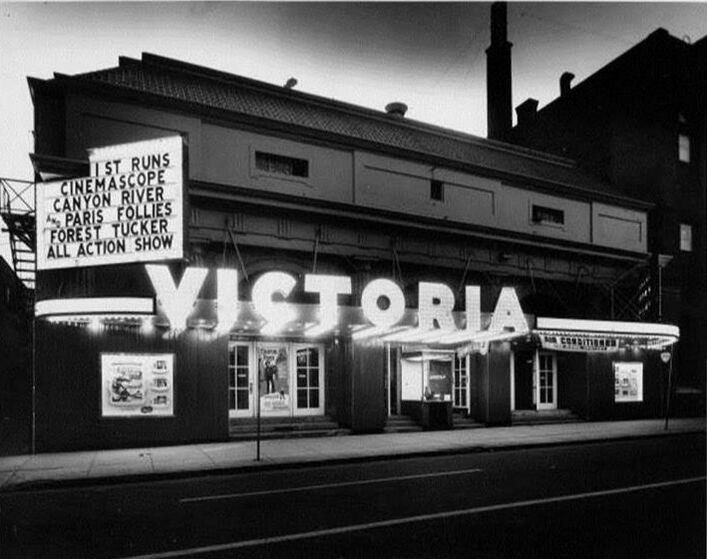

The Talbot Streetscape in its prime, looking north The Talbot Streetscape in its prime, looking north LONDON, ONTARIO – For those of us who alternately enjoy and suffer from our status as lifelong Londoners, the sense of loss we can experience when demolition or an extensive architectural makeover messes with some beloved cityscape, can be almost as desolating as the death of an old friend. Considering that the only investment we have in such properties is emotional or associative, our grief in such instances is a kind of indulgence that we’re not really entitled to. We’re not on the hook for maintaining or upgrading such buildings. We don’t have to pay for the impracticality of perpetuating the outmoded and we don’t have to try to find tenants to rent out such relics and somehow make them sort of viable. And yet when property owners or landlords do what they deem necessary to turn some sort of profit, we can nonetheless feel violated and robbed; as if they’ve just made off with some significant portion of our civic identity and didn’t have the decency to check with us first to see if we were amenable. It's touchy, tetchy stuff that can breed outrage and resentment for developers and conservationists alike. London’s most notorious act of architectural desecration in my adult lifetime was the razing of an entire block’s worth of substantive and historically significant 19th century commercial buildings (including one of our first city halls) that ran along the west side of Talbot Street between Dundas and King (see photo above). It was the last unbroken block of Victorian storefronts in London and its loss was doubly maddening because for a brief period (thanks to the heroic efforts of lawyer David Winninger who was then an MPP in Bob Rae’s NDP government) the City had won a heritage designation to protect the block from any developer who didn’t have a solid, City-approved plan for what would take its place; a protection they heedlessly threw away 28 years ago this fall. Eventually, the levelled block gave rise to that hockey and performance arena which I still insist on calling the John Labatt Centre (as 'Budweisser' is not a name that shall ever pass my lips). And the developer of the JLC even gave a tokenistic nod to we vanquished preservationists by replicating the façade of the old Talbot Inn on the structure’s northeast corner. This was a pointless little touch that irritated many and truly satisfied no one; rather like those recitations of utterly passive guilt that get rattled off before gatherings and performances by white toast liberals where obeisance is paid to the various indigenous tribes who supposedly own this land which we're just borrowing for a few centuries without actually doing anything honourable or real like paying rent. With the passage of time, my feelings of outrage about the fate of that block have considerably softened. Summoning a maturity and perspective that eluded me 27 and a half years ago, I now have to admit the most startling development in this whole matter for me: those hard-assed agents of realism and commerce actually had a valid point. What seemed such a heartless and brazen imposition of the modern on the old, ultimately did more to revitalize downtown than would ever have been accomplished by preserving that string of 19th century shops and warehouses. And there also was a solid upside for the preservation-minded that grew out of that decade-long battle to try to save the Talbot Streetscape. The protesters raised such a ruckus in trying to hang onto those buildings that citizens and politicians alike snapped out of their slumber regarding the easy destruction of London’s built heritage. We still lose more magnificent old treasures than I wish we did but the pace of destruction has slackened off greatly from the frenzy we knew in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. Nobody gets to set the wrecking ball swinging on heritage buildings today without a lot more consultation, argy-bargy and red tape. Bewilderingly enough (considering the appeal such institutions make to history and tradition and continuity) our two big downtown cathedrals have been among the worst heritage culprits in subsequent years. No small part of the majesty of St. Paul’s Cathedral was the way it occupied its half-block sized lot, surrounded to the north, west and south by lush lawns and old shade-giving trees. To cut through from Queens Avenue on a July afternoon and take the corner-shaving walkway through to Richmond Street, was to discover a different kind of sanctuary than churches usually provide; a welcome buffer from noise and heat. While those grounds still offer a few minutes' refuge from the fumes and the racket of downtown, the stylistic and symmetrical perfection of the church’s old setting has been marred by the imposition of a klutzy diocesan office on the south lawn. And one block to the north the Catholics committed an even worse act of barbarism in tearing down the imposing four-storey rectory just east of St. Peter’s Cathedral Basilica and moving their church offices into the bland 1950’s school building on the north side of their parking lot. Cheaper and easier to maintain, no doubt, but churches are supposed to signify more than pragmatism and the bottom line. I see in the latest edition of our quarterly parish newspaper that we’re going to have to either shore up or fill in the now abandoned and deteriorating tunnel which used to link the rectory to the cathedral. I remember being led through there by the choir director one blizzardy Christmas Eve when I was one of the readers at the midnight Mass and marvelling that such a facility – installed at who knows how much expense just to forgo a 150-foot trudge over snowy terrain – even existed. There is a sort of gooey weak-mindedness that those of an architecturally conservative bent need to beware of; do we truly stand for the cause of heritage or nostalgia? Do we reflexively insist that just because a building has always stood somewhere, it must remain? There might be nothing particularly admirable or distinguished about a structure at all but because it has served as some sort of time-marking backdrop to your life, a familiar attachment is thereby formed and you mistake that sentimental connection for historical significance. For me, the old Victoria Theatre on Clarence Street (between Dundas and Queens) is a particularly pungent case in point. I’d been longing to clap my eyes on a photo of the Victoria for years and when one finally turned up while doing a scan on the Vintage London website, those eyeballs filled up with preposterous tears. I realize I’m probably alone in my exalted feelings for the place. Aesthetically, architecturally, I know there was nothing to recommend the Victoria but this was the pleasure palace of my earliest youth. Originally opened in 1915 as a vaudeville house, it had been converted to a second-run cinema by the time I came to sample its creaky charms, and was universally regarded by all the adults in my life as a quasi-derelict ‘fleapit’. The seats were abominable, spring-shot ruins. The place always smelled dank. The soles of your sneakers adhered to the sticky, soda-spilled floor as if outfitted with suction cups. And I have friends who swear they sited furry rodents rooting through discarded popcorn bags for crumbs and un-popped kernels.

But none of that mattered a jot because this was the cinematic emporium that screened just the kind of unspeakable dreck that appealed to savagely ignorant nine and ten year-old boys – the early, garishly coloured Hammer horror films, the high-camp Vincent Price / Edgar Allen Poe vehicles, an occasional revival of a Karloff, Lugosi or Chaney black and white classic, lots of Tarzan and gangster movies, Three Stooges festivals and, most appealing of all to me and my childhood chums, the Italian-made (and appallingly dubbed) muscleman movies starring that master thespian, bodybuilder and one-time Mr. Universe, Steve Reeves (1926–2000). Admission as I recall was a quarter, maybe 35 cents by the end, and the cheapest item at the refreshment stand was a kind of soft white toffee plugged with coloured ju-jubey bits that sold for a nickel. Called Roman Nougat, it was the perfect complement to one of Reeves ‘sword and sandal’ epics. I remember my utter incredulity in whatever year the Victoria screened it, to learn that Hercules Unchained wasn’t nominated for an Oscar in any category whatsoever. Okay, maybe it wasn’t the Best Picture of the year but that bit where they inter-cut between close-ups of a roaring lion’s face and shots of the gruesomely thick-thighed Mr. Reeves wrestling a big hairy blanket to the ground . . . surely a Best Editing statuette was in order for such cinematic wizardry. I also remember the double bill the Victoria ran in 1965 (months before they tore the place down) that killed off my boyish enthusiasm for horror films for good. Trying to multiply their audience by crudely merging two genres and bankrolling the whole venture with a combined budget of at least $300, Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter and Billy the Kid Versus Dracula (starring a cadaverous-looking John Carradine as the mysterious Count Alucard – get it?) were wit-deficient stinkeroos that made Ed Wood look like David Lean. It was a somewhat sobering pleasure to finally find some old photographs of the place and wallow in the fond associations that were recalled to mind. And, considering that the cleared land on which it stood for 50 years has now been a bloody parking lot for 54 years, perhaps I can even question what their hurry was in tearing it down. But today I do realize that most of the films the Victoria ran were irredeemable crap and the place itself was a bit of a dump. So really, I can let it go. Victoria Theatre Photo Credit: Canadian Architectural Archives, Library & Cultural Resources, University of Calgary

1 Comment

|

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed