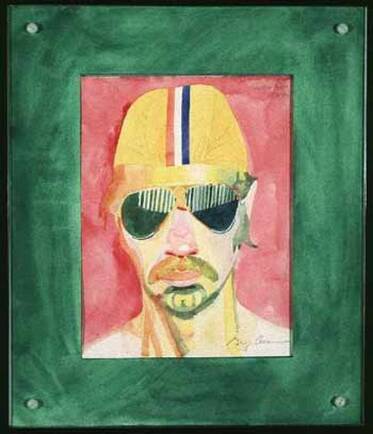

Greg Curnoe: Self-portrait, July 10, 1980 Greg Curnoe: Self-portrait, July 10, 1980 LONDON, ONTARIO – This excerpt from Three Artists: Kurelek, Chambers & Curnoe (Elmwood Press, 2016) examines two of Greg Curnoe’s most pronounced qualities – his utter lack of a religious gene and his impassioned devotion to London, Ontario – and muses on some of the higher mysteries of inspiration, affiliation and rechanneling. My oldest brother Dave was tooling around in our parents’ car one autumn night in the mid ‘60s when he drove down Weston Street and pointed out a rather boxy and flat-roofed house to me. “That’s where Greg Curnoe lives,’ he said. “It used to be a factory.” “Who’s Greg Curnoe?” I asked in my ignorance which was profoundly deep and total. I would have been 14 or 15 years old. “He’s an artist,” said Dave, and a whole series of cosmic tumblers fell into place in my skull and the universe suddenly became more interesting. This was the first time I’d heard of an artist who wasn’t dead or who didn’t live so far away that I’d probably never get to see his house. The implications of this were staggering. “It can happen here,” I thought. “It can happen now.” This very attractive and empowering idea that art could be and was being made here was an encouragement – indeed a kind of epiphany – that Curnoe provided and continues to provide more than 20 years after his death for more London artists of all kinds than we will ever be able to enumerate. For Curnoe, there was no deprivation (indeed, there were many benefits) to living and working in a place that might be perceived as a cultural backwater. He believed that wherever an artist happened to live was fine. In fact there was more potential for a really original vision to flourish away from the usual centres. In Nowheresville an artist was less likely to get caught up in passing fads and sensations and would be better able to shut out any distracting media buzz and instead zero in on the forces in his own life and immediate environment that most fascinated him. A big Curnoe watercolour from 1988 featured a pair of sunglasses, a guidebook and a touristy t-shirt floating in the air over Lake Huron. On the front of the shirt were printed four place names of international importance – London, Paris, Rome and Grand Bend. The Bend, of course, is London’s beach playground on Lake Huron, 40 miles to the north. But Curnoe being Curnoe, London – and for that matter, perhaps Paris as well – were winking references to the Ontario cities that bear those names. Yes, it was a joke but yes (as with most of Curnoe’s jokes), on some significant level he meant it too. Curnoe believed that the operational factor in art and life is the consciousness of the perceiver: that anywhere on planet Earth could serve quite nicely as the doorway to experience and truth. Unlike the other two artists examined in this study, Greg Curnoe (1936–92) was not a Roman Catholic. Indeed, he felt no attraction whatsoever to any of the world’s religions, at least as a reasoning adolescent and then adult who could no longer be hauled off to Calvary United Church on Sunday mornings by his parents. According to all the reports of those who knew him best, he was as thoroughgoing a religious sceptic as ever drew breath but probably owing to his rarely-failing lightness of touch and humour and also perhaps as a mark of respect for both of his parents and particularly his mother whose faith was deep and sincere, this scepticism never emerged in his art or his conversation as animosity but only as bemused indifference or incomprehension. His friend Bob McKenzie (one of the great chroniclers of London cultural lore who died shortly after this book was published) told me that the usual Curnoe answer for any inquiry of a religious or mystical nature was: “I don’t think about those things.” In his 1984 essay, Oregionalism: Geocentrism and the Notion of Originality which appeared in the first issue of Provincial Essays, poet and writer Christopher Dewdney wrote of his friend: “Curnoe, for his part, has always had a profound mistrust of mysticism or anything that smacked of the irrational or psychological, any system of belief or theory, in fact, that supplanted logical and clearly perceivable descriptions with anything that referred to hidden realities or symbolic meanings. For Greg Curnoe, reality is inherently apparent and perceivable to the clear thinking individual possessed of common sense. Mystic concerns only confuse the issue, bringing in seemingly deliberate complications where none are necessary.” For somebody whose life was so much of a piece, who had such a rare and heightened sense of fidelity and loyalty, and for whom continuity and keeping in touch with his earliest influences and inspirations was so important, it can seem surprising that having been exposed to church as a child, Curnoe let it go so completely as an adult, never referenced religion as an artist. And yet a case is made by some brave souls that Curnoe’s own religious capacity wasn’t so much jettisoned as rechanneled. In his final recorded interview with me over Christmas of 2013, Ross Woodman (then in the process of a radical reappraisal and upgrading of Curnoe’s worth) said, “Greg is not religious in any recognizable sense but his dedication to and his personal identification with London struck me as religious – a Protestant religiousness. But talk to Curnoe and he would say that was sheer nonsense and I would understand that.” Woodman was his usual insightful self in identifying the distinctly Protestant flavour of Curnoe’s quasi-religious devotion to London. Unlike Kurelek or Chambers, Curnoe – who read independently and widely and attained a far broader and deeper grasp of the art scene than either of those artistic compatriots – never aspired to situate himself within some larger tradition or insert himself into an established milieu. Unlike Kurelek, Curnoe never wished there was some way to release his paintings without signing them. Indeed his very particular personality was central to his art-making; both in its in-studio conception and execution as well as in its public reception. In saying this, I am not suggesting that Curnoe was encumbered with any more ego or self-regard than any artist requires to create something and believe that other people might want to look at it as well. Curnoe was not a self-regarding fathead and repeatedly displayed a selfless concern for the welfare of other lesser known artists. Celebrity came to him early and he repeatedly did what he could to – if not push away exactly – at least broaden the range of fame’s spotlight so that its warmth and glow fell upon other practitioners as well. The work he produced in the 1960s when he enjoyed his greatest celebrity as the newest sensation wasn’t a patch in terms of craftsmanship and realization on the work of his maturity. But in a way that isn’t true in encountering the best work of Kurelek or Chambers, some knowledge of Curnoe’s personality was a necessary prerequisite to ‘getting’ what he was up to. This was particularly so at first but even towards the end of his life, Curnoe was still producing the occasional work whose full appreciation hinged on one’s knowledge of and interest in Curnoe the personality rather than Curnoe the artist - such as a bold lettered work from 1987 that asked the questions: “WHAT IF DAILY LIFE IN CANADA IS BORING? WHAT IF I AM NOT AWARE OF WHAT IS INTERESTING TO OTHERS ABOUT MY LIFE?” Unlike Chambers, Curnoe would never submit to any school’s regimen regarding how art should be made. For Curnoe there was no such thing as a universal curriculum for an education in visual art. As long as the aspiring artist honed his craft and faithfully followed his own curiosity, he’d be all right. Yes, Curnoe made a point of knowing what was going on in other times and other places but he was determined to emulate none of it. The distinctly Protestant note that Woodman identifies is struck in the way that Curnoe always kicked against the idea that there were authorities or centres of power that needed to be referenced or deferred to. He might listen to what certain experts had to say or check out what scenes were unfolding in certain cities or countries but ultimately he would be responsible for his education and his practice. He would figure it all out for himself and go his very own way by staying where he was and being answerable to no one else, thank you very much. British Columbia-based poet, historian and university professor George Bowering recalls that, “Greg didn’t like it when he was called a pop artist. I think it was mainly because in the ‘60s the pop artists were USAmerican. It was a USAmerican phenomenon and a USAmerican name. Greg said he was interested in neglected Canadian details and the stuff that was around him in his life. The pop artists were after the attention of the fickle New York gallery shoppers. He was not pop and he was not op, the other buzzword in newspapers of the time. To get him mad I used to call him pop. Jeez, he would say, and rub his nose with his knuckles. What kind of artist are you then? I’m a London artist, he would say, every time.” Curnoe’s devotion to London was the most stubborn and the most original thing about him; the most endearing, the most perverse and the most inspiring. Though he would never have phrased it this way, for Greg Curnoe, London, Ontario was The New Jerusalem – the ideal city and the only city (at least as far as he was concerned and he had difficulty seeing this might not be the case for others) where all could be fulfilled. I remember interviewing Christopher Dewdney in the mid ‘80s shortly after Dewdney had landed work at York University and had finally decided he really would have to leave his hometown and move to Toronto. He was deeply touched – and I couldn’t help sensing, a little appalled – at how fervently Curnoe had beseeched him and badgered him to not give up on London; insisting not just that London needed him but that for the purpose of realizing his poetic gifts most fully, Dewdney needed London. London writer and university professor Stan Dragland (who ultimately left London too but at least had the decency to hang in until after Curnoe died) spoke for literally hundreds of London artists, writers and musicians when he shared his memory of Curnoe with journalist Doug Fetherling in a memorial cover story in Canadian Art magazine in the summer of 1993: “I met him at Michael Ondaatje’s house here in 1970, the year I moved to London. The Nihilist Spasm Band, I must say, made awful music that cured me for years of wanting to hear any more like it. Yet from such things I came to know that I could live and work in London. In all the years I’ve been here, Greg laboured to make an arts community, trying to fold people into it.” In that same article, Dewdney summarized the centrality of London to Curnoe’s life and art: “For him, sense of place was essential, part of his empiricism. In all Greg’s work, there is the awareness of ‘This is my place.’ That, he felt, was the only real subject. He felt that to compare what one was doing with other localities or styles was the worst provincialism. Such was the grammar of his experience: regional identity first, but conscious of what went on elsewhere.” In her 2001 family memoir, My Brother Greg (published by London-based Ergo Productions) Lynda Curnoe produced just the kind of book that Greg would’ve loved; an unpretentious and downright account of her oldest brother’s life that takes great care to situate him in his familial and geographic contexts – the two classifications from which he derived his greatest sense of meaning and belonging. George Bowering’s memoir, The Moustache: Memories of Greg Curnoe (Coach House Press, 1993) appeared the year after Greg’s death, whereas Lynda Curnoe waited almost a decade before bringing her book forth. Hungrily reading both memoirs soon after their publication, I responded rhapsodically to Bowering’s because here was a guy who was really on Greg’s wavelength and who talked the same lingo, moved in the same bohemian circles and had an insider’s access to his subject. Lynda’s book in comparison seemed kind of pedestrian and stodgy, heavy on the meat and potatoes and not much sauce. I’ve gone back and re-read both of them this year and was surprised to discover that my reactions to these very different texts have completely reversed over the intervening years. Now that Greg’s been gone for a quarter century and time has marched on in its inexorable, world-transforming, detail-erasing way, I profoundly appreciate the care Lynda Curnoe has taken to fill in the background and particulars of her story. Bowering’s book, a collection of quick snapshot-style memories rather than a full portrait, still works for me when he recalls certain quintessential Curnoe gestures - the ever-handy pencil parked behind his right ear, the quick knuckle rub on the side of his head or his nose when formulating a thought - or his characteristic manners of speech. Greg was always so gentle about disagreeing with you and would preface his contrary remarks with some kind of genial softener of which Bowering supplies two: “I’m not sure I agree with that,” and “That’s an interesting way of looking at it.” But for the most part, Bowering’s book no longer tells me enough whereas Lynda’s book tells me just the sort of stuff I now want to know – where Greg went to school and how he got along with his teachers, what were the comics and trading cards and pop bottles he collected, how did he interact with his parents and his siblings, what were his summer jobs. No one but Lynda would risk appearing so banal as to include a paragraph like the following in her memoir of her famous brother: “Our Porter grandparents lived only one block west of us, at the corner of Wharncliffe Road and Langarth, in another house built by my grandfather. The Porters’ presence defined the neighbourhood for us, so that it seemed to belong to us. We were always walking up to Grandma’s house and it was like our second home. As teenagers, Greg and [younger brother] Glen took turns mowing their lawn every week. Greg and [cousin] Gary spent hours sitting on their front porch listing the makes and models of cars that whizzed by on Wharncliffe Road, Highway 2, that linked London with Lambeth, Port Stanley and other towns to the south.” As I say, all that might strike some readers as unremarkable - though that note about seeming to own the neighbourhood of his earliest youth helps to explain the enormous confidence that Greg possessed even as a child and which always drew people to him as a scene-maker. But his fellow townsmen (or at least this one) levitate with bliss at the mention of familiar London street names just as we feel a surge of nostalgic recognition when gazing at his early collage works that incorporate old LTC bus transfers, O Pee Chee bubble gum wrappers and cardboard Silverwood’s milk lids; though secretly we wonder, “Can this work be as meaningful for anyone who didn’t grow up in London handling civic trinkets like these?” Writer, English professor, art patron and critic Ross Woodman (1922–2014) – whose musings did so much to bring coherence and attention to the work of at least two generations of London artists – moved here from Winnipeg as a young man. I asked him if he thought some knowledge of London was necessary before a person could ‘get’ Curnoe? “I never thought that,” he said. “I thought that getting Curnoe was a way of getting to London. And also a way of getting out of London in terms of what he did with that kind of material. Yeh, I can see Curnoe getting to you because you are very much caught up in the concrete, detailed life of London as a writer so your newspaper columns and articles on London would fit with Curnoe in a way I can recognize.” Sheila Curnoe has no doubt that her husband would have thoroughly approved of Lynda’s book. “I supported Lynda completely when she wrote that book,” Sheila told me. “You came here from England at the age of 15,” I said to Sheila. “So living with someone for whom life in London Ontario was so central, so unquestionable . . . Could you always relate?” “It was funny. I didn’t understand it at the time. We would go to 74 Langarth Street for supper with his mom and then we would get in the car. Driving home down the streets he would say, ‘There’s Mr. McIntosh’s house and I delivered papers there. And I delivered papers there. And over there too.’ And I’d think, ‘Jesus Christ, do we have to do this every single time? I don’t care where you delivered papers.’ Now I see it differently. It was so important to Greg. These things were so important. Just this month I was driving up to Stratford with Robin and I couldn’t stop remarking on how beautiful it is. The trees, the colours, the fields. I’ve felt this way for some time; that I am now looking at London and Ontario through Greg’s eyes. And I value it so much more now. He would argue with George Bowering about how much more beautiful Ontario was than B.C. because B.C. is just over the top with its mountains and everything . . . it’s trying too hard. When I look at the countryside now and I see how well we live here and all these idiots complaining about things . . . I think, ‘Look at what you have here. And value what you have. He felt these things so strongly. And I think it came from the family – that rootedness. He was so unique and very special. He saw things differently than anyone else. And he was so taken with the blue colour of the Ontario sky. There’s a certain blue that happens and he would have to stop everything and go out and look at it. Or sunsets. It was physical for him. He just loved it.”  The very Curnoe colour scheme of Mackies The very Curnoe colour scheme of Mackies And on the not-so-mundane side, consider this little revelation that Lynda casually drops on page 42, citing the local origin of the colour theory employed throughout the career of an artist celebrated as a most unorthodox colourist. “In the 1920s and 30s, many young Londoners had summer holidays in nearby Port Stanley. Mum often spent hers there at Ruth Bright’s parents’ cottage on Bessie Street. The London and Port Stanley Railway carried trainloads of passengers to the lake every weekend. Port Stanley, on the shore of Lake Erie, had a famous dance pavilion called the Stork Club where Mum and her friends would go to dance. It also had a restaurant on the boardwalk called Mackies, distinctively painted bright orange and blue, colours Greg said had attracted him as a child and later influenced him as an artist.”  Greg Curnoe: Car, 1967. Collection: Museum London Greg Curnoe: Car, 1967. Collection: Museum London Any discussion of Greg Curnoe’s art – whether it’s about his figurative work or his lettered work, the earlier, cruder oil paintings which first brought him wide renown or the more precisely accomplished water colours that he started producing in the later 1970’s when he wasn’t so much of a media darling – makes mention of his bold use of intense colour combinations that simply shouldn’t work but in his case most brilliantly do. The end papers for the catalogue of his great 2001 retrospective, Life & Stuff, are the very same hot shade of pink that I’ve only ever seen in two other books – one a cultural history of the Barbie doll and the other, Barry Humphries’ mock autobiography of his comic alter ego, Dame Edna Everage, My Gorgeous Life. Curnoe’s colour sense was one of the most original things about him and here his sister matter-of-factly explains that one significant origin of that originality was something he picked up for free as a kid with a frosty glass of Orangeade.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed