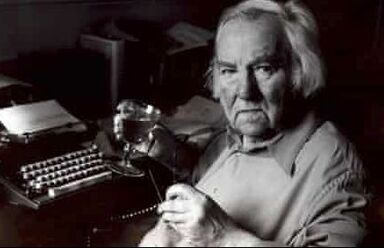

KEITH WATERHOUSE (1929 - 2009) KEITH WATERHOUSE (1929 - 2009) LONDON, ONTARIO - Now here’s a little tribute to a writer I’ve adored for most of my life and am reasonably confident that nobody else on the planet will be commemorating this week. For one, he’s dead and has been so for twelve years. Out of sight and out of mind. And at this point in his obscurity I don't sense that anybody’s inclined just yet to start considering whether he’s got the makings of a classic. The man had a peerlessly unpretentious style, a devastating sense of the absurd and a seemingly instinctive genius for imparting delight - none of them qualities, methinks, that carry much weight in the too self-conscious literary marketplace today. And there are a couple other aspects that would seem to work against the odds of anyone making large or serious claims for Keith Waterhouse today. Part of the problem is that he wrote so bloody much, the vast majority of it journalism. His columns were rapturously consumed in their day but as there are few things less enticing than even the wittiest take on last year’s political squabbles, the shelf life for a lot of his journalism was short. If you're interested in sampling what he could do in that field, a nearly four-decade compendium of his less ephemeral journalism, Waterhouse at Large (1985) gathers up the best of his miscellaneous commentary. When he wasn't cranking out fodder for newspapers, the ever-industrious Waterhouse whipped off about fifteen novels, and a handful of stage plays and screenplays of wildly varying quality. I’ll be talking about the best of his fictional work below but right off the top it has to be admitted that at least half of his novels are rather strained jokes about chaps who drink too much and exasperate women and forget where they parked their car and suffer other such indignities and misadventures common to the lush and the louche. Loving the cast of Waterhouse's mind as I do, I’m happy to read such fare once but such novels frankly do not bear rereading or recommending to the non-indulgent.

Considering the staggering quantity of booze he poured down the hatch every day of his adult life - he admitted he was a heavy drinker but denied he was alcoholic - Keith Waterhouse was probably lucky to make it to the age of 80 and doubly blessed that he remained so remarkably productive right up to the very last lap, submitting his final twice-weekly column to England’s Daily Mail just four months before his death. That column, headlined, It’s English as She is Spoke Innit? cast a sceptical eye on a new task-force report on educational reform for seven to eleven years-olds, and showcased just two of his many areas of unassuming expertise. Waterhouse’s astonishing first novel, There Is a Happy Land (1957), was written from the perspective of a ten year-old kid (heading off Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole by two decades and Roddy Doyle’s Paddy Clarke by three) and displayed his never-flagging insight into the psyche and spirit of England’s youngest citizens. Also evident in that final column was his formidable knowledge of the English language and how to wield it. In 1980 he wrote the style book for the Daily Mirror where he then had a regular column, revising it a few years later as Waterhouse on Newspaper Style, which became a standard reference book used throughout the industry. A Fleet Street legend of the old school, Waterhouse signed off on formal education at the age of 14 and began selling columns to northern newspapers while still in his teens. He made his way down to London from harrowingly humble beginnings in Leeds, of which he wrote with tremendous affection and humour in his first volume of autobiography, City Lights (1994). Waterhouse was the youngest of five children whose costermonger father died when the budding writer was only three. Pushing his dilapidated vegetable cart on his daily rounds, Waterhouse’s old man was known to call out (one imagines the ironic intonations of W.C. Fields') that the "master-grocer" was approaching; evincing that same beautifully tuned sense of the harsh disparity between life as it's imagined and life as it's lived that would drive so much of his son’s writing. His single most popular novel, Billy Liar (1959) - later adapted as a stage play, a movie, and a musical but never, alas, said Waterhouse, as Billy Liar on Ice - is the study of a very likable but weak-willed young man who constructs an engrossingly rich fantasy life to help him cope with a maddeningly circumscribed existence as a clerk in an undertaker’s establishment who still lives at home with Mom, Dad and Gran, and is all too aware that the best years of his life are being hopelessly frittered away. The fatal catch is that those same fantasies that make Billy's banal existence bearable also keep him rooted to the spot; defusing his drive to clear out and set up somewhere else on his own terms. It was doubtless because of his hardscrabble beginnings that however much success Waterhouse erratically enjoyed as a novelist, playwright and screen writer, he was never tempted to turn his back on the dependable wages of his journalistic work. A subsequent autobiographical volume, Streets Ahead (1995) recounts his progress as a writer in all of these fields. Though Waterhouse developed scripts with esteemed directors like Walt Disney, Franco Zeffirelli and Alfred Hitchcock and hobnobbed with such illustrious stars as Peter O’Toole, Judi Dench and Alan Bates, his head was never turned by show biz celebrity. By far the greatest part of Streets Ahead is devoted to his rhapsodic evocation of the delights and wonders of mid-20th century Fleet Street as seen through the eyes of an eager young pup just down from the north who can’t quite believe his luck in landing any sort of job on that fabled avenue. His single most successful play, Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, (about his good friend who penned the Low Life column in The Spectator and whose more than occasional hung over absence would be explained in the weekly magazine with that titular notice) is yet another expression of Waterhouse’s love for the journalistic milieu. When the late and thuggish media mogul, Robert Maxwell (father of the dreadful Ghislaine now awaiting her comeuppance) took over the Daily Mirror, Waterhouse instinctively recognized that this bully was no friend of newspapers and refused to write for him, no matter how much Maxwell offered to keep the Mirror’s favourite columnist on board. “Cap’n Bob,” he mockingly called him, as he picked up his battered old Adler typewriter and walked across the road to hang out his columnist’s shingle at the Daily Mail for the rest of his career. My own unknowing introduction to Keith Waterhouse came in my tenth year when I somehow persuaded my parents that for our once-in-a-blue-moon family outing to the cinema, we ought to go to our neighbourhood theatre (the same fleapit that always ran the Carry On series) for a very limited engagement of an obscure little something I’d seen advertised in the paper as Whistle Down the Wind. I knew nothing about this film whatsoever but the meaningless (to me) title (the phrase apparently hails from the world of falconry) excited my heart in some inexplicable way. The movie knocked me sideways as a kid but then most movies did back then. Re-encountering it about fifteen years ago, I admired it more than ever. In his sublime screenplay about three northern farm kids who believe not only that the second coming is at hand but that Jesus Christ has chosen to make his reappearance in their barn, the utterly unreligious Waterhouse developed a poignantly comic parable about innocence and religious belief. Another film that’s well worth catching is A Kind of Loving, Waterhouse’s adaptation of an early Stan Barstow novel that brilliantly explores the challenges of an impetuous (which is to say, shotgun) marriage that gets off to a horrific start complete with the mother in law from Hell in residence in the same flat. What might seem at first like just another story about a tiresome, commitment-phobic adolescent male, opens up into a richly rewarding study of extended family dynamics, exploring how men and women and parents and children both encourage and exploit one another. The development of my special regard for Keith Waterhouse had a lot to do with timing and serendipity. During my teens some genie at the CBC television network programmed a lot of Waterhouse’s films in their late movie slot and that was when I really started looking out for anything I could find to read or watch that had his name on it. He became as important to me as The Beatles and that great inundation of bands that constituted the British Invasion in helping me to throw off the too-slick American cultural artifacts that I’d been steeped in from my birth and to open my eyes to older traditions and a wider and grittier and more richly eccentric world.

2 Comments

Jim Ross

13/7/2021 08:05:27 pm

Herman - I was 45, and on a barmy friend's recommendation, I gathered my wife-and-kids under my arms to watch, for the first time, Whistle Down the Wind. The script took all of my babies to places their Dad would never have dreamed to take them. At the same time, the three young characters in the film brought all of us close to emotional fires of indescribable heat, and none of us could step away from the scalding.

Reply

Susan Cassan

14/7/2021 06:40:24 am

Thanks for the expanded view of Waterhouse. I was very familiar with Billy Liar, but had no idea of his extensive film writing career. This has opened lots of doors to look for more of his work.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed