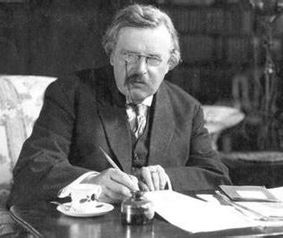

GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON LONDON, ONTARIO – I first became aware of G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) in my late 20s on a literary tip from my friend Jeff Cencich. “I think you’ll like this guy,” he said, dropping a copy of his Selected Essays on the counter of City Lights Book Shop where I was working as a clerk. As I identified with Chesterton so immediately and so strongly, I’m glad that introduction wasn’t made any sooner; that my character and literary proclivities were more or less established before he arrived on my scene. We’re both inclined to portliness, we both have walrus moustaches, we share a birthday, and we both enjoy the composition of humorous essays. The overlap between us (cue Twilight Zone music) was a little spooky. I admire the man tremendously but I’d hate to be accused of aping him Of course, the date of my birth was my parents’ idea (though I’m not sure they sat down with a calendar for 1952, circled the 29th of May and said, ‘Let’s shoot for that one’); the moustache, rotundity and writing, I came up with on my own. Yet even arriving as late in my life as he did, the scope for influence was still there. While he hasn’t formed, he’s at least firmed up a number of my convictions about journalism and literature, society and the family, and he played no small part in calling my bluff on my perpetually postponed showdown with Christianity; dragging me, not quite kicking and screaming, into the Roman Catholic fold.

There are dozens of writers I admire but Chesterton and Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709–84) are heroes. Dr. Johnson, I might mention shares a birthday with my brother Ted to whom I’ve just mailed a copy of Fr. Ian Ker's superb 900 page anthology, The Everyman Chesterton, for his 71st birthday. (What were my parents trying to get at?) They both were the subjects of sprawling, very frank and very indulgent biographies written shortly after their deaths by people who’d known them well; James Boswell for Johnson and publisher Maisie Ward for Chesterton. In spite of all their reported weaknesses and fears, contradictions and warts, the portraits that emerge are riveting in their originality, wisdom, kindness and goodness. Both men came with so many different parts yet both were so completely ‘of a piece’. They didn’t have to become meek dopes in order to become Christians. Their faith didn’t rest upon powder kegs of doubt too dangerous to examine. They didn’t stand in judgement of others of differing views but instead engaged and wrestled with them whenever possible and had enormous fun in the process. It occurs to me that both these physically substantial and quintessentially English gents would make ideal models for Toby jugs. As new collections of Chesterton’s work are still being occasionally unearthed and published – Basil Howe, a novel composed in his 19th year, was recently assembled from a bewildering cache of 19th century notebooks that turned up in the bottom of a trunk of non-literary paraphernalia following the death of Chesterton’s last secretary – the total number of works published under the name of Gilbert Keith Chesterton will certainly add up to more than 200 separate volumes. Usually the only writers who compile such staggering monuments to literary industry (‘Come on down, Barbara Cartland’) are the worst kind of hacks or are good enough writers who establish a narrow turf which they can easily work over and over again. What astonishes one in appraising the work of Chesterton is the number of different literary categories in which he excelled. HE FIRST MADE HIS MARK as an essayist and literary critic, writing in a highly flamboyant and personal style, quickly grabbing the attention of readers and editors who clamoured and negotiated for more. Chesterton’s mind was always open to distractions and different facets of any subject he tackled and by quickly over-committing himself to virtually any newspaper or magazine that came calling, he began very early to take on the persona of the absent-minded genius which became so large a part of his legend. In other books and articles of the period, one is always coming across sightings of Chesterton: halting traffic on Fleet Street as he stands in the middle of the road scribbling on bits of paper; distractedly ordering dinner in restaurants while debating with his friends, then letting that dinner go cold; once misplacing a fried egg which he swept off the table while gesturing to make a point; dining at the House of Commons with a boot on one foot and a slipper on the other; stopping himself cold in town one day, certain he was forgetting an appointment and wiring home to his patient wife, Frances: “Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?” But Chesterton’s absence of mind in daily affairs only evinced his astonishing presence of mind in other matters. Imagine the shock of the bored American journalist who asked this dithering eccentric what book he’d take to the proverbial desert island and Chesterton calmly answered: “I think I should take Thomas’ Guide to Practical Shipbuilding.” (It wasn’t just a brilliant riposte; he named an actual book.) Asked in a public debate to comment on the apparent success of the female enfranchisement movement, Chesterton gave spontaneous utterance to the kind of zinger that most writers could spend a week constructing and polishing: “Twenty million young women rose to their feet with the cry, ‘We will not be dictated to,’ and promptly became stenographers.” Lecturing once on Dante’s Inferno at Notre Dame College in the States, he dealt at some length with a supplementary question and then tried to get back on track by asking, “Now, where in Hell were we?” On the page, levity and fun are almost always part of the proceedings but the insights go deeper, ranging from the fairly straightforward (“The relations of the sexes are mystical, are and ought to be irrational. Every gentleman should take off his head to a lady”) to the paradoxical (“For children are innocent and crave justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy”) to the profound (“The whole difference between construction and creation is exactly this: that a thing constructed can only be loved after it is constructed, but a thing created is loved before it exists”). THERE ARE SINGLE PARAGRAPHS in Chesterton’s work (and one’s coming up right now; a tangent hailing from his critical study of Charles Dickens) that contain more original ideas than most writers manage to juggle in a book: “People talk with a quite astonishing gravity about the inequality or equality of the sexes; as if there possibly could be any inequality between a lock and a key. Wherever there is no element of variety, wherever all the items literally have an identical aim, there is at once and of necessity, inequality. A woman is only inferior to a man in the matter of being not so manly; she is inferior in nothing else. Man is inferior to woman in so far as he is not a woman; there is no other reason. And the same applies in some degree to all genuine differences. It is a great mistake to suppose that love unites and unifies men. Love diversifies them because love is directed toward individuality. The thing that really unites men and makes them like to each other is hatred. The more modern nations detest each other, the more meekly they follow each other; for all competition is in its nature only a furious plagiarism. As competition means always similarity, it is equally true that similarity always means inequality. If everything is trying to be green, some things will be greener than others; but there is an immortal and indestructible equality between green and red.” As I say, that paragraph above is a flourish off to the side of his main subject. Early on in the book - and writing at a time when not so much was known about Dickens’ appalling treatment of his wife nor the tetchiness of his relations with his publishers and professional colleagues – Chesterton latched onto a situation from Dickens’ infancy and brilliantly employed it as a kind of template for his entire life and career. Commenting on how Dickens’ father used to get the boy to sing songs and provide entertainment for his elders, Chesterton writes: “Some of the earliest glimpses we have of Charles Dickens show him to us perched on some chair or table singing comic songs in an atmosphere of perpetual applause. So, almost as soon as he can toddle, he steps into the glare of the footlights. He never stepped out of it until he died . . . Dickens had all his life the faults of the little boy who is kept up too late at night. The boy in such a case exhibits a psychological paradox; he is a little too irritable because he is a little too happy. Like the over-wrought child in society, he was splendidly sociable, and yet suddenly quarrelsome. In all the practical relations of his life he was what the child is in the last hours of an evening party, genuinely delighted, genuinely delightful, genuinely affectionate and happy, and yet in some strange way fundamentally exasperated and dangerously close to tears.” When you pick up a book by G.K. Chesterton you are imbibing stories and essays – often journalism – that is 85 to 120 years old. How can it still be interesting, so applicable to life and the world as we know them today? Only because the man unfailingly bypassed almost everything we think of as ‘news’ and wrote instead about all those trivial and cosmic matters that will fascinate and bedevil the human race unto extinction – like books and ideas, religion and love, beer and skittles, cheese and croquet. Nothing was too common or insignificant to look at it again with new eyes. The fact that anything was taken for granted or overlooked was, for Chesterton, a flashing signal that he’d probably stumbled upon something here of fundamental importance. I give you some essay titles selected at random: On Lying in Bed (How’s this for an irresistible opening sentence? “Lying in bed would be an altogether perfect and supreme experience if only one had a coloured pencil long enough to draw on the ceiling”); What I Found in My Pocket; On Running After One’s Hat (an activity which Chesterton claimed was only slightly less embarrassing than running after one’s wife); Logic and Lawn Tennis; The Glory of Grey . . . you get the idea. CHESTERTON LOVED THE ROUGH and sloppy world of journalism, regarded himself as a journalist first and a serious writer not at all. “I would rather live now and die, from an artistic point of view,” he said, “than keep aloof and write things that will remain in the world hundreds of years after my death.” He liked journalism’s immediacy of response, the give and take and the tussling with an enormous audience. When book contracts started to come his way, he wouldn’t scale back his journalistic commitments and his appalling working habits didn’t change either. In preparation for his numerous biographies of writers and saints, he would routinely get his secretary to gather together mountains of pertinent material and after the most desultory of scans, he would plough ahead and write the books mostly from memory and rumination. “Anything worth doing is worth doing badly,” he said by way of explaining how even his own autobiography is riddled with incorrect dates and incidents out of sequence. He was scarcely more careful when writing about other men’s lives and many of those biographies come with a fair share of the kind of mistakes that are known to give more punctilious librarians the hives. The value of those books when they worked – and no one denies the brilliance of his Dickens, Browning, St. Francis or Thomas Aquinas – wasn’t their biographical veracity (the strokes were much too broad and reckless for that) as their author’s uncanny ability to isolate and magnify the important truths that no one had ever latched onto before. Etienne Gilson, the renowned Thomistic scholar who devoted entire volumes to single facets of Aquinas’ life and thought, greeted the appearance of Chesterton’s 180-page study of the saint by saying, “Chesterton makes one despair. I have been studying St. Thomas all my life and I could never have written such a book.” CHESTERTON'S TWO LITERARY SURVEYS, The Victorian Age in Literature (a book which was commissioned and then prefaced with a short disclaimer by the nervous English publishing house of Williams and Norgate), and Heretics, (a book-length dispute with most of the influential writers of the Edwardian era) also display to stunning effect his knack for diving through walls of preconceptions and clichés and emerging with new and essential insights. His two greatest works of Christian apologetics, Orthodoxy (his ‘slovenly’ spiritual autobiography) and The Everlasting Man, (a God-centred history of the world; his answer to H.G. Wells’ Outline of History) stand alone with some of the books of C.S. Lewis (who himself was profoundly influenced by Chesterton) as the best Christian apologetics of the 20th century. In the fields of the novel and poetry, Chesterton’s reputation hasn’t fared so well. Poetically he excelled at comic verse and ballads, scoring achievements and popularity in his day but is currently ignored by critics and academics who seem to have this thing against any modern poet who’d exhibit such bad taste as to be a practicing Christian, to cheerfully shun despair and to rhyme. Anthologists such as Kingsley Amis and W.H. Auden always included a few of his verses but for the most part Chesterton’s poetry – accessible, populist and rhythmically stirring – couldn’t be more at odds, more delightfully irrelevant to contemporary and dominant poetic trends. Although I cherish many of his novels and stories, I feel a little sorry for anyone who first approaches Chesterton through his fiction. He never created a full character in his life but preferred to dress up ideas in human form and make them fight and dance. While some of his mysteries required that he create the semblance of a plot, these never received half so much of his attention as the weirdly charged atmospheres and settings of these stories and the moral and philosophical debates which ensued at their climax. The Father Brown mysteries were so hugely popular in their day, that they supported both Chesterton’s household and his less than profitable weekly newspaper, first called The New Witness and then G.K.’s Weekly. But nowadays it’s Chesterton fanatics and not your usual mystery buffs who have much use for the Father Brown series at all. Too bad for them. They’re missing out on some great stuff. Consider this little gem of a speech from The Flying Stars, in which the dashing criminal Flambeau has disappeared into the upper reaches of a stand of trees at night and Father Brown beseeches him from below to give back the diamonds whose theft has framed an innocent young man: “I want you to give them back Flambeau, and I want you to give up this life. There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don’t fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I’ve known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime . . . I know the woods look very free behind you, Flambeau; I know that you could melt into them like a monkey. But some day you will be an old grey monkey. You will sit up in your free forest cold at heart and close to death, and the tree-tops will be very bare . . . Your downward steps have begun. You used to boast of doing nothing mean, but you are doing something mean tonight. You are leaving suspicion on an honest boy with a good deal against him already; you are separating him from the woman he loves and who loves him. But you will do meaner things than that before you die.” SOME OF HIS NOVELS – like The Man Who Was Thursday and The Ball and The Cross – read like the work of a decidedly non-suicidal Franz Kafka. Of all his fiction, my own favourite is Manalive. Maisie Ward, his first and best biographer, calls Manalive the Chestertonian acid test; if you can stand it, you can stand anything he wrote. He is so cheerful, so funny, so brilliant in this book, that he’s obnoxious. It’s interesting to compare the characters of Chesterton and his good friend, H.G. Wells. In the end they were almost equally prolific and embodied an almost equal number of contradictions. But Wells’ contradictions were serial. He was always abandoning or denouncing one of his previous enthusiasms in order to pick up on another; eroding his credibility en route and ending his life in depletion and despair with the publication of Mind at the End of Its Tether; the last pathetic bleat of this thoroughly intelligent man who somehow never learned to temper his own fickle extremism. Chesterton’s contradictions were simultaneous. His enthusiasms didn’t cancel out or threaten each other but rather emphasized and intensified each other until they attained the multifaceted, mind-wrenching beauty of lively coexistence which we call ‘paradox’. I know that Chesterton actually bewilders and irritates some readers. They can’t get a handle on him. They can’t tell when he’s serious. (He’s always serious or, at least, sincere.) They think he writes like he’s on drugs. In his poetry or his prose, his fiction or his essays, at the top of his form or not, I always find in Chesterton an affirmation of life and gratitude for its gift; an unflagging and contagious sense of wonder and amazement at the world in which he lives. In Orthodoxy Chesterton explains how it was that he eventually came to Christian belief. He’d dabbled in spiritualism and Ouija boards just long enough to get sickened, to attain what he called ‘a bad smell in the mind’. There were dark powers to be tapped into but Chesterton knew enough to know that he wanted nothing more to do with them. He turned and walked away, shut that door for good. But still he was spiritually hungry. He hung onto the idea of God by what he called ‘a thin thread of thanks’. He didn’t particularly hunger for Heaven or righteousness or salvation. All he really wanted was someone to say thank you to. That enormous impulse of gratitude is, I expect, fairly rare. If you don’t feel it in any measure, then I suspect that Chesterton is not your man. Chesterton was fond of recalling an old riddle from his childhood. What did the first frog say when he finally met God? ‘Lord, how you made me jump!’ That too was an exclamation of thanks and a distillation of the wonderful spirit of this man – ungainly, high-spirited, grotesquely beautiful; jumping for joy in the face of God.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed