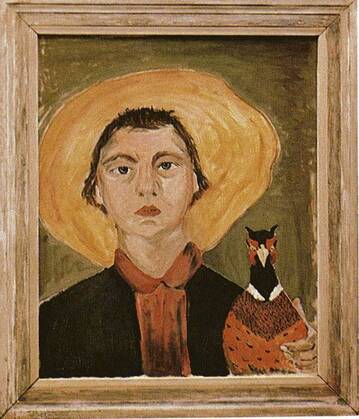

LONDON, ONTARIO – The American short story writer and novelist, Flannery O’Connor (1925-64), was always ready to joke about her Catholic faith and the apparently crazy things it drew out of her and made her do. She knew there were times others bristled at the depths of her convictions, and would attempt to head them off at the pass, proclaiming, "You shall know the truth, and it will make you odd." But she wasn’t prepared to soft-pedal (let alone deny) her faith for the sake of keeping any social exchange pleasant; not even one that could advance her literary career if she played her conversational cards diplomatically. Her epistolary account of how she stunk out the joint at a salon-type evening at Mary McCarthy’s is one of the highlights of her collected letters, entitled, The Habit of Being: “I was once, five or six years ago [this would make her about 25] taken by some friends to have dinner with Mary McCarthy and her husband . . . She departed the Church at the age of 15 and is a Big Intellectual. We went at eight and at one, I hadn’t opened my mouth once, there being nothing for me in such company to say . . . Having me there was like having a dog present who had been trained to say a few words but overcome with inadequacy had forgotten them. Well, toward morning the conversation turned on the Eucharist, which I, being the Catholic, was obviously supposed to defend. [Mary McCarthy] said when she was a child and received the Host, she thought of it as the Holy Ghost, He being the ‘most portable’ person of the Trinity; now she thought of it as a symbol and implied that it was a pretty good one. I then said, in a very shaky voice, ‘Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it.’ That was all the defense I was capable of but I realize now this is all I will ever be able to say about it, outside of a story, except that it is the centre of existence for me; all the rest of life is expendable.” In his one hour documentary, Flannery O’Connor: The Storyteller, Bishop Robert Barron of the Word on Fire Institute, comments on this courageous declaration that it should never be interpreted as the frightened utterance of some threatened literalist who was pooh-poohing the value of symbolism. Though only two collections of short stories (A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Everything That Rises Must Converge) and two novels (Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away) appeared in her short lifetime, O’Connor is universally hailed as one of the finest American writers of the 20th century. This singularly accomplished artist had no lack of appreciation for the power and the value of symbolism and metaphor and analogy and all the other tools in a writer’s chest. She would be the last person in the world to deny the utility and importance of symbolism. But even in the face of social ruination, she would not demote the dreadful and demanding primacy of faith to the level of an intellectual comfort or conceit. She knew full well the sort of mediocre cesspool where that sort of sloppy thinking led: "One of the effects of modern liberal Protestantism has been gradually to turn religion into poetry and therapy, to make truth vaguer and vaguer and more and more relative, to banish intellectual distinctions, to depend on feeling instead of thought, and gradually to come to believe that God has no power, that he cannot communicate with us, cannot reveal himself to us, indeed has not done so, and that religion is our own sweet invention." Or, as she put it more succinctly on another occasion: "What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross." A bit of an anomaly from birth, Flannery O’Connor was the only child of devout Catholic parents in Savannah, Georgia; a region of the southern United States which many would designate as the centermost buckle of the Protestant bible belt. Catholics weren’t so thin on the ground that they didn’t have their own churches scattered here and there (and some of them quite handsome) but they were members of a poor minority, rarely able to rise in Georgia society, and were generally regarded as pretty rare birds – like the peacocks which O’Connor raised at Andalusia, the family’s rural home where her widowed mother ran a dairy farm. O’Connor also briefly raised swans and at the age of five, she somehow taught a chicken to walk backwards; an amazing feat which aroused such interest that a Pathe film crew was dispatched to record the maneuver for one of their newsreel presentations that were screened in theatres along with previews and cartoons before the big feature. The girl’s prize chicken, however, pulled a Norma Desmond on the day the Pathe crew arrived and refused to perform its amazing trick on cue; a reticence which the impatient director overcame (in a 1930 instance of ‘fake news’) by simply running the footage backwards for that section of his report. After her death from lupus (a debilitating and intractable disease which she contracted from her father who died when O’Connor was fifteen) the peacock became her personal emblem. In some form or other – fan open and radiantly splayed or trailing behind like an exotic bridal train – a peacock is invariably worked into her book jackets and other illustrative commemorations such as postage stamps.  In a touching photograph by Joe McTyre of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, O’Connor stands supported by long aluminum crutches on the front steps of Andalusia in a dark summer dress. Her face is slightly puffy from the steroid medications she was taking and her wing-tipped glasses (which she never would trade in for something more stylish or flattering) further accentuate her owlish face. Her crutches are pointing backwards and outwards ever-so-slightly and this stance mirrors, almost perfectly, a curious and confident peacock who approaches along the top step with his own protruding tail feathers and long white quills scritching over the bricks. McTyre's photo also illustrates what O'Connor was getting at when she joked to one of her correspondents that when she was standing around on those crutches, they made her look like "a structure with flying buttresses." Like many other writers, O’Connor had dreamed as a young woman of fleeing that corner of the country where she was born and making a name for herself elsewhere. As a university student who won residencies at prestigious writers’ workshops in Iowa and at Yaddo and landed early stories in the best quarterlies and journals, all that seemed to be coming together for her. But she had no sooner finished the final draft of her first novel, Wise Blood, over the winter of 1950/51 then it became clear that her lithe body was being stiffened and wracked, her energy sharply depleted (allowing her, at most, three hours a day for writing) and her horizons radically diminished by the very same disease that had carried away her father ten years before. Living on her own, significant travelling, marrying and having children or even contemplating some sort of romance . . . all of that was suddenly and permanently placed beyond her reach. At the age of twenty-five and perched on the brink of what promised to be a brilliant career, she had to place herself in the full time care of her decidedly practical and woefully unimaginative mother. Regina O’Connor devotedly loved Flannery and wanted the best for her in her chosen career but couldn’t really understand or appreciate what she was up to. Regina became infamous among Flannery’s many visiting colleagues and friends for taking them aside while her daughter was having a restorative nap and asking if there was anything they could do to persuade her to write nicer and more cheerful stories. Mother and daughter would chat together over breakfast every day with the local newspaper close to hand to provide conversational grist and, quite often, details and ideas for Flannery’s stories. Regina encouraged friends to drop around and even stay over for a few days - which meant that she would be operating a restaurant and inn as well as a dairy farm - knowing that it did Flannery good to spark ideas with people who really shared her interests. Stubborn and conventional as she undoubtedly was, Regina nearly always had the grace to honour Flannery’s work; taking care to not burden her with any concerns that might fog up her mind and leaving her to it during those few productive hours each day. No small part of what makes Flannery O’Connor such a compelling figure is her apparently serene acceptance of a fate that seems so pitiless; the pleasures and satisfactions she derives in circumstances so reduced. In a 1953 letter to the poet, Robert Lowell, O’Connor writes: “I am making out fine in spite of any conflicting stories . . . I have enough energy to write with and as that is all I have any business doing anyhow, I can with one eye squinted take it all as a blessing. What you have to measure out, you come to observe more closely, or so I tell myself.” In 1979, O’Connor’s good friend Sally Fitzgerald published the magnificent collection of O’Connor’s letters, The Habit of Being, which admirably serves as the autobiography which she never had the time to write. In her introduction to that bumper collection of nearly six hundred pages which she compiled and edited over fifteen years, Fitzgerald offers this last word on the relationship between Miss and Mrs. O’Connor: “On the subject of Mrs. O’Connor herself, I can report a remark that Flannery made to me the last time I talked to her. She told me that she had fully come to terms with her confinement and with the physical danger in which she lived; that she had, in fact, only one great fear – that her mother would die before she did. ‘I don’t know,’ she said, ‘what I would do without her.’ The letters themselves are full of Mrs. O’Connor; she is quoted, referred to, relished and admired, joked with and about, altogether clearly loved.” Indeed, for those who find it hard to make much headway with Flannery O’Connor’s fiction which can seem so coarse and brutal to the uninitiated, these letters smooth the path admirably, acclimatizing you to her droll southern humour and her unfailing eye for a telling detail, her generosity of spirit and steady good nature and her courageous determination to state a thing as she sees it. Herewith, a few of my favourite observations plucked from The Habit of Being: "Writing is like giving birth to a piano sideways. Anyone who perseveres is either talented or nuts." “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.” "You have to cherish the world at the same time that you struggle to endure it." "Total non-retention has kept my education from being a burden to me." "To know oneself is, above all, to know what one lacks. It is to measure oneself against Truth, and not the other way around. The first product of self-knowledge is humility." And, of course, ‘Truth’ with a capital ‘T’ brings us back to Flannery O’Connor’s faith. She read widely and deeply in theological works and jokingly identified herself as a “hillbilly Thomist”. She was, I would say, about as thorough-going a Catholic as ever drew breath and seems never to have entertained a moment of serious doubt. In Brad Gooch’s superb 2009 biography of O’Connor, Flannery, one of her childhood friends recalls Flannery at the age of six choosing to pass on the special children’s mass in the basement of the cathedral and instead attend the un-watered-down Mass upstairs a couple hours later with her parents. Challenged by one of the nuns at her parochial school the next Monday morning about her attendance, this friend recalls, “She’d stand there and tell sister, ‘The Catholic Church does not dictate to my family what time I go to Mass.’ I was five and she was six and I knew she was different.” Notre Dame philosophy professor (and author of the Father Dowling mysteries) Ralph McInerny identified what puzzles and puts off many people when they first read O’Connor’s fiction: “If she was a Catholic author, if her writing was influenced by her faith, O’Connor almost never chose Catholic subjects for her stories. Her characters are the underclass of the South, most of them haunted by a fundamentalist, Bible-thumping, evangelical Christianity. Her ability imaginatively to occupy the outlook of men and women and children almost retarded in their simplicity is equaled only by Steinbeck in Of Mice and Men.” In that same documentary on O’Connor that I mentioned above, Bishop Barron likened the menacingly unreflective simplicity of so many of her characters to the pathetically endearing thugs who populate the movies of the Coen Brothers; the kind of instinct-driven brutes who avidly chow down on a stack of syrup-smothered flapjacks at the International House of Pancakes before cramming somebody’s bodily remains through the gummy portal atop the shredding gears of a wood-chipper. It often puzzled readers why O’Connor always peopled her blackly comic and sometimes outrageously violent tales with manic and even unhinged Protestants. A fan once wrote to her asking why it was that, though she had been a Catholic all of her life and all of her writing was drenched in Christian imagery and themes, her weird and grotesque characters, from the most secretive brooders to the most raving fanatics, were invariably Protestants. O’Connor answered: “To a lot of Protestants I know, monks and nuns are fanatics, none greater. And to a lot of monks and nuns I know, my Protestant prophets are fanatics. For my part, I think the only difference between them is that if you are a Catholic and have this intensity of belief, you join the convent and are heard from no more; whereas if you are a Protestant and have it, there is no convent for you to join and you go about in the world getting into all sorts of trouble and drawing the wrath of people who don’t believe anything much at all down on your head. This is why I can write about Protestant believers better than Catholic believers – because they express their belief in diverse kinds of dramatic action which is obvious enough for me catch.” O’Connor found that the unchanging creed and the rich multi-formity of Catholic worship had a way of accommodating, transforming or answering almost any dilemma that a Catholic might encounter in the course of life. And wonderfully reassuring and sustaining as this was for her personally, it didn’t make for the kind of drama O’Connor required in her stories. Stark old Protestantism on the other hand, was always drawing such props and traditions out of the way, changing the rules of membership and tweaking their beliefs to align them with a shifting social/moral consensus and thus throwing its adherents back onto nothing more than the vitality of his or her own private relationship with God at this very moment. In short, both churches had God-crazed zealots to contend with but the Catholics had ways and means of constructively containing theirs.  Flannery O'Connor: Self-Portrait Flannery O'Connor: Self-Portrait In Flannery O’Connor’s single most celebrated short story, A Good Man is Hard to Find, a horrible controlling grandmother inadvertently leads her family to their hideously violent doom. This snobby, bossy busybody, always wanting things her way and fretting about how things will look to others, is only able to escape the spinning hamster’s training wheel that is her mind for a few seconds when she suddenly apprehends the awful mystery and tragedy of the tormented misfit who has killed everybody else in her family and now points his gun at her. When she reaches out to touch this deformed and suffering soul in a moment of self-forgetting compassion, he draws back in revulsion and plugs her in the chest with three bullets. “She would have been a good woman,” he tells one of his accomplices later, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” Bishop Barron points out in his documentary that for her final fifteen years, lupus was O’Connor’s stand-in for the misfit, graciously poised to shoot her every minute of her life; giving her the clarity to see things as they are in every possible circumstance and dimension and the courage to tell the truth in her uniquely hilarious and harrowing way. In a more subdued and thoughtful tone in one of her later letters, O’Connor expressed the same insight like this: "In a sense sickness is a place, more instructive than a long trip to Europe, and it's always a place where there's no company, where nobody can follow. Sickness before death is a very appropriate thing and I think those who don't have it miss one of God's mercies."

6 Comments

SUE CASSAN

20/4/2020 07:52:18 pm

O’Connor is one of the most amazing writers of the past century. Incredible powers of observation and writing as precise and deadly as a scalpel, she is utterly unique. As every page came at such a cost, she had no time to waste on anything less than brilliance. You have Napier’s me to visit her again.

Reply

David Warren

20/4/2020 09:34:20 pm

Have just forwarded your wonderful piece on Miss O'Connor to all of my electronicised seminary students, elsewhere in the world.

Reply

Wonderful piece, Herman. If it's fine with you, I too may use your piece for my own writing students. We do study A Good Man, such a remarkable piece, almost over the top, really, but one I like to note for what it says about what I call the theology of art. Last spring I was in Savannah and visited Flannery's old home. From her bedroom window as a young child she had a clear view of the Catholic Cathedral -- St. John the Baptist -- that would influence her life and writing so much. Thanks for your own keen eye of observation, Herman, and may your pen continue to enliven and enlighten.

Reply

21/4/2020 09:57:59 am

Herman, did you know that Mary McCarthy's son, Reuel Wilson, was a Professor of Modern Languages at UWO, though few knew that he was the son of two of the most brilliant intellectuals of twentieth-century USA?

Reply

Max Lucchesi

21/4/2020 11:15:07 am

Good introduction to Flannery O’Connor, Herman. The lady has my sympathy. Even hale and hearty Catholics were given a hard time in pre WW2. southern states. As a counterpoint, may I offer your readers two other authors who struggled throughout their lives with sicknesses that finally killed them? The first, Giacomo Leopardi 1798-1837, was born into an impoverished aristocratic family at Recanati then a village in the defunct Papal States. His parents were devout Catholics, his father Count Montaldo who, though he loved literature and had an extensive library was a conservative reactionary and was said to be the last Italian aristocrat to wear a sword. His mother Marchioness Antici Mattei, a cold disciplinarian who disallowed anything not approved of by the church. Giacomo always a weakly and frail child was probably afflicted with Ankylosing Spondylitis disease. He, his sister Paolina and his younger brother Carlo Orazio were tutored by Father Sebastiano Sanchini but, according to Count Montaldo Giacomo at ten years old had already learned as much as the tutor could teach him. From then on Giacomo retreated to the library and taught himself. By the age of eighteen had mastered Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Spanish, French and English, ruined his health and destroyed the sight of one eye. Had begun a correspondence with the classical scholar Pietro Giordani and translated from the Latin; Hesiod, Dionysus of Halicarnassus, written sonnets in the style of Petrarch and the Florentine Ser Pecora. In 1818 his two poems 'Al Italia and 'Sopra il Monumento di Dante' were published in Rome, and he disappointed his parents by refusing to become a priest. In 1824 his first volume of poetry ‘Canzoni’ was published which included the poem 'a la Luna'. The poem's sixteen lines encapsulated everything that will follow in two centuries of Western lyric poetry, and began to establish him as an important Italian poet. In 1835, two years before his death he signed a contract with Severino Starita to collect the complete editions of his works, gather them together and publish them in six volumes. The second volume ‘Canti’ contained his collected poems and established him as the foremost 19th,Century Italian poet and one of the most significant of the European modern poets. Posthumous publications continued and in 1898-1900 his notebook Zibaldone di Pensieri (the word Zibaldone is Veneziano vernacular and means a hodgepodge) was discovered and published. It established Leopardi as one of the most important thinkers of his time and is compared to Coleridge, Emerson, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. The wonder of his life is how, with his frequent periods of illness, blindness and poverty he managed to be as prolific as he was. Canti wasn’t translated into English until 1900 and the the complete Zibaldone not until 2013, all 6400 hand-written pages of it.

Reply

Max Lucchesi - part two

21/4/2020 11:21:32 am

My next offering is Antonio Gramschi. 1891-1937. Gramschi has been compared to Nelson Mandela in that both were Communists and both earned the respect of their jailers. Mussolini declared of him when he was brought to trial. "We must stop that brain from thinking for at least twenty years." Gramschi was born in Sardinia. His father came from the mainland and was a minor civil servant, his mother of Sardinian peasant stock. He was one of seven children, small in stature physically handicapped, a hunch back and suffered from Potts disease. The family's poverty was made worse when the father was made a scapegoat and imprisoned on trumped up corruption charges to protect more senior functionaries. At eleven years old despite his infirmities he worked ten hours a day six and a half days a week. Still he managed to educate himself and pass his high school diploma. At nineteen he was writing for the local newspaper. In 1911 he won a scholarship to the University of Turin. He left the University half way through his degree saying " an intellectual's duty is to educate the working man in the street not to sit and think in safety". By 1914 he was writing for the Socialist newspaper 'Il Grido del Popolo' and educating and unionizing the Fiat workers. After the war, in 1918 with Togliatti he founded the radical magazine Avanti., ironically edited by Mussolini for the short time he was a socialist. Gramschi's wide ranging articles for Avanti cover not only economic and social questions, but literary and theatrical criticism. The failure of the 1920 Turin general strike because of the Socialist Party's refusal to support it and the infighting that followed led in 1921 to the birth of the Italian Communist Party. Togliatti who became its leader said of Gramschi. " His intellectual seriousness, repugnance of any kind of demagoguery and great personal modesty prevented him assuming leadership as he should have done" After Mussolini's march on Rome, Gramschi in 1922 left for Moscow where he met Julia Schuct a violinist whom he married in 1923. Because of illnesses he stayed in Moscow until 1924, seeing the birth of their first child. He returned to Italy where he was elected to Parliament. He denounced equally Mussolini and Stalin, comparing the Black Shirt gangs to the bullying Bandar-logs of Kipling's Jungle book. In 1925 Julia came to Italy but left in 1926 after Gramschi was, despite Parliamentary Immunity arrested. She returned to Moscow pregnant and gave birth to their second son, whom Gramschi was never to see. It is upon the ten years, 1927-1937, that he spent in prison that his reputation truly rests. 'Prison Note Books' (smuggled out at his death) expressing his wide ranging social, economic and political theories, have influenced much of the world's social democratic thinking. Yes he was a true democrat and 'Letters from Prison' shows his moral courage and innate morality. He is probably the only Marxist thinker whose work is still relevant today., and his only flaw is that he wasn’t a poet.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed