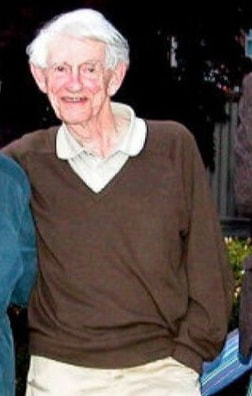

NORM IBSEN NORM IBSEN LONDON, ONTARIO – Norm Ibsen who died in London last week just a couple weeks before his nintieth birthday, was the first editor I encountered when I started to write as a freelance journalist in May of 1979. Up to that point my only real goal in life was to write fiction and – surprise, surprise – that wasn’t working out very well for me. I had the usual aspiring writer’s drawer full of unpublished novels and short stories, hundreds of bad poems and a couple frustrated stabs at play scripts. But the only writing that had made it into print were unpaid features in the last three editions of a fast-failing music magazine out of Toronto and one novel with an equally desperate publishing house in London who did manage to cut me one royalty cheque (which covered off the costs of one month’s worth of electricity in my slum of an apartment) before they too went belly-up. My actual paying occupation at that time was dishwashing and one and a half years into marriage, that just wasn’t cutting it anymore. It was time – indeed it was past time – to switch my professional focus to something that reputedly paid. My ignorance of the newspaper world was just about total and I now recognize that my attitude toward journalism generally was pretty arrogant and dismissive. I considered it a poor cousin to more creative literary forms and approached it with trepidation as a potentially talent-sapping trap. Determined to make my living as a writer in this one-newspaper town, I didn’t have to torture myself for very long in deciding which organ to try to sell my soul to. There were however two further questions which threw a little shade on my prospects of signing that Faustian contract. With my lack of even a high school graduation diploma, would the Free Press gatekeepers give me the time of day? And were whatever literary gifts I possessed sufficiently plastic that I could mold them into any sort of shape that a newspaper would want?

To suss out my potential market, I bought a fine, fat Saturday edition of The London Free Press (I swear it weighed at least three pounds) and went whipping through section after section to determine just what sort of journalism I could imagine myself writing. Stories about politics and wars, sports and business, collisions and robberies, fashion and cars . . . I couldn’t relate to any of it. Then I happened upon the book review pages; the same pages on which, four years earlier, I’d received a decently generous appraisal of my first novel. Heck, I bought and read books – lots of them – and I was loaded with opinions. This might be the place to try to hang my hat. The next Monday I called the paper and arranged to meet with the editor who managed the book review pages on Thursday afternoon. I threw on the most business-like outfit I could assemble and, sweating and itching profusely, made my way into Norm’s air-conditioned office on editorial row. When I told him I was interested in reviewing books, he didn’t laugh or ask me to explain what made me think I was qualified to pass judgement on other writers’ work. Instead he plucked two books from one of the lower of the spilling-over shelves of new releases and told me he’d like two 1,000-word reviews in about four weeks if I could manage that. When I got home I wrote up a brief account of my meeting with the man who, more than anyone else, would help me devise a way to make my living from writing: MAY 10, 1979 – Met Norm Ibsen at the Freeps today and was quite taken by the man. He was enormously helpful, willing to come down to whatever level I required and in his whole demeanour seemed to be saying, “I too am interested in seeing you write for us.” No rushing, no skepticism, no intimidation. I was really impressed. He seems to be a shy man with rather large ears, a bit of a rash dancing on his forehead and a notably dry mouth. But his face is unusually kind and I was fascinated by the way he can alternately look middle-aged or old, depending on the angle and the light. About three times I seemed to have all the information that was necessary and, feeling he must be busy, made motions toward packing up, only to have him think of something else and re-open the talk, usually to ask me more about books and what I liked to read. He gave me two books to review, one of which seems quite intriguing; the other I suspect might be pretty housewifey and dumb. But here we go.” As I got to know the lay of the land in Norm’s office, I learned that those lower shelves is where the duds, orphans, long shots and total obscurities languished; unrequested volumes that no one had spoken for and which might never get reviewed at all and no one would much care except possibly the authors. Among the lessons I learned in writing up those first two reviews was the importance of casting aside preconceptions and being open enough in one’s reading to attend to what a writer has actually accomplished. In both cases, my first impressions (one looks hopeful, one looks stupid) were flipped. I gave encouraging praise to Mrs. Job by Victoria Branden, a more-than-competent first novel in the key of Constance Beresford Howe, and utterly savaged a megalomaniacal memoir by Justin Thomas – How I overcame my fear of whores, royalty, gays, teachers, hippies, psychiatrists, athletes, transvestites, clergymen, police, children, bullies, politicians, nuns, grandparents, doctors, celebrities, gurus, judges, artists, critics, mothers, fathers, publishers and myself – that was every bit as obnoxious as its title. To show him that I meant business, Norm received both reviews by the next Monday morning and our beautiful working relationship was up and running. Soon Norm started to throw me interviewing assignments with visiting writers that could be made into features. One of these with the decidedly dishy Barbara Amiel, netted me my first accredited plug on the back cover of the paperback edition of her Confessions and an inscription in my hardcover copy commending me for being so remarkably quiet and attentive. Several years later I was even more thrilled when my review of Anne Tyler’s previous novel was cited on the back cover of the first hardcover edition of Back When We Were Grownups. (Though in both those cases, one of the ‘d’s was dropped from Goodden.) By the end of that first summer I twigged to the fact that in addition to editing the book review pages and selecting each day’s cache of Letters to the Editor (arguably the best read page of any newspaper) Norm also edited something called the 'op/ed' or opinion/editorial pages. In addition to unsigned editorials reflecting the newspaper’s official position on timely topics, these two pages featured opinion columns from a wide range of local, national and international writers, including such heavy hitters as Art Buchwald, George Will, William Safire and Bernard Levin. Though I'd grown up in a house which received a Free Press every day, I’d never spent two seconds on those pages before and quickly surmised that – while all of it wasn’t top flight stuff – such columns were directly related to the literary and personal essays I admired by such great writers as George Orwell, Malcom Muggeridge, Keith Waterhouse, John Updike, G.K. Chesterton and good old Samuel Johnson. With Norm’s blessing I took a shot at that page, starting out innocuously enough with a quasi-poetic celebration of Forest City trees. When I got my next cheque I happily discovered that op/eds paid three times better than book reviews. (And I'd previously absorbed the hard truth that reviewing one book by somebody else paid better than writing a book of my own.) And so began my almost 35 year run of commentating in the Freeps, which was only interrupted twice at the behest of Free Press editors-in-chief – first in the mid ‘90s when I edited Scene for four years and then when I edited The London Yodeller for three years. London’s big daily seemed to construe these ditzy arts bi-weeklies as competition which was rather small-hearted of them I must say. When The Yodeller sadly breathed its last in the fall of 2016, I pitched them several columns to see if I could reactivate our relationship one more time but there was no longer room in the greatly depleted Freeps for me. Indeed there isn’t room for much at all anymore and they only crank out the thinnest of editions five days a week now. I note with real disappointment that a full week after his passing, the newspaper to which Norm Ibsen contributed so much, hasn’t seen fit to even acknowledge that milestone. I’ll always be grateful that Norm served as my introduction to the profession if only because he messed so little with my inclinations and instincts and was so welcoming of my enthusiasms. If I say I can only recall two occasions when Norm rejected my initiatives, even that would be overstating it as he never really had to say ‘no’. In February of 1978, Robert O’Driscoll of the University of Toronto hosted a two week symposium on Celtic culture which drew specialists and scholars from around the globe. The 55 essays delivered at this symposium saw publication the next year in a limited edition of 500 copies of The Celtic Consciousness; a book which sold for the heart-stopping price of $125. I immediately recognized that this was my kind of hooey (both precious and pernicious) and braced myself to mortgage my entire teen-aged record collection to raise the retail price until a review copy magically showed up on Norm’s shelves. I was incredulous when Norm told me I was welcome to the book but he didn’t think a review would be necessary. He didn’t say as much but the look on his face suggested that he found the very idea of a specifically Celtic Consciousness to be a flakey bit of business with possibly dangerous implications; a dubious early exercise in witless identity politics (Celtic Lives Matter) which shouldn’t be honoured or encouraged with a review. I raced through the book in a misty-eyed rapture and was startled when I took it up again a decade later and found that, yes indeed, I had worked my way over to Norm’s point of view. Another time, under the influence of a teacher friend who was bemoaning the bad press which her strike-happy union was then eliciting, I went seriously overboard in the other direction, cranking out an unhinged essay praising teachers to the skies. I was perusing the new arrivals shelf as Norm read through my first page and I heard him make an involuntary noise as if he were having difficulty digesting his lunch. I turned around to look at him and he subtly arched an eyebrow and asked, “Do you really want to say this?” “Yeh, you’re right,” I answered, instantly recognizing everything that was wrong with the piece, and snatched the pages from his hand and stuffed them in my back pocket. “We shall speak of this no more.” At the heart of our working relationship always was the love of books; a quality which has pretty well gone missing in the upper echelons of the newspaper world today. In that pre-internet era when I had to cycle down to his office with every fresh burst of genius, Norm always found time to discuss what I was reading and made usually sound suggestions of other authors I might want to try. I couldn’t help noticing that Norm’s own favourite writers – E.B. White, James Thurber, Maurice Baring, Hugh Kingsmill – all shared his gentleness and winsomeness and his exquisitely tuned gift for genial understatement. When I made my first book-buying safaris over to Britain in the ‘90s, Norm went to considerable bother to draw me up lists and maps to direct me to the best second hand shops. I remember one shop called Thornton’s that he put me on to – several tube and transfer points away from the bibliophilic hub of Charing Cross Road and Cecil Court in London – that more than lived up to his astonished exhortation: “I’ve never seen so many Ronald Knox titles in one shop.” I couldn’t tell you where that shop was today. I only went there once on the first or second day of what turned out to be their going-out-of-business sale and scored a once in a lifetime deal on about a third of the Knox titles in my collection. But I have been back to Thornton’s in several tantalizing dreams since then. Perhaps his finest, fiercest hour as a bibliomaniac came in the mid ‘80s when Norm was told his Saturday book pages must go. They weren’t paying their way in terms of ad revenue and two pages once a week devoted to book reviews was deemed unjustifiable by the bean-counters upstairs. Norm refused to comply. He stood up against management and sacrificed one of his editorial pages every Friday to book reviews until his overlords came to their senses and relented; giving him back his space until he retired about a decade later. I WROTE TO MY longtime freelance compatriot Paula Adamick with the news of Norm’s passing last week and she got back to me with this tribute a couple days later: “Norm Ibsen – God bless him – unquestionably the best books editor The London Free Press ever had. One of those great minds in a back room who says little, yet regularly asserts itself in surprising ways. How often I’ve thought about him over the years. And how, without even asking me, he’d select a book for me to review that was so invariably suited to my interests and quirks as to be uncanny. All without a word. And mostly I wasn’t surprised by his choices. Except for one that stands out in my memory – Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, (1988), then unknown. Yet within weeks it became controversial around the world. And remains so. Why me? I wondered. It wasn`t until much later that I realized that Norm wanted the book reviewed through a religious – not political – filter. “But this was just one example of how his deep knowledge and love of books made him so quietly influential. Norm always seemed to know all the books coming on the scene in every season and just which ones he deemed important and influential enough to be worthy of review. And on this, he was invariably correct. In this way, Norm Ibsen exerted real influence on the minds of Londoners who anticipated the ever popular Books Pages every Saturday in the London Free Press. Long may he be as remembered for his discerning tastes as he will be loved always by those who knew him.” After Norm’s retirement, I’d dependably bump into him twice a year at the London Record Show in the basement of Centennial Hall where he’d be flipping his way through crates of second hand jazz LPs in search of rare pressings and would always pull himself away to chat with me for a few minutes before getting back to his work of diligent excavation. I dropped in for the visitation when his wife, Joy, died in 2008 and got my only glimpse of Norm the family man in the company of his three children, greeting the friends who’d dropped by to pay their respects. I’d always known him to be diffident and shy and wondered if and how much he'd ever be able to truly relax. Even as difficult as those circumstances were, I was happy to see the natural and easygoing affection – given and received – that enveloped him in that room. In 2013 Norm and his family made headlines around the world when genealogical sleuthing determined that Norm’s three children – through their mother – carried Mitochondrial DNA which flagged their connection to the notorious Richard III whose skeleton had just been unearthed during excavations underneath a downtown parking lot in Leicester. The British-born Joy had known that she was distantly related to Prime Minister William Pitt but wasn't aware that a particular line of DNA (which is only passed on by women) and was tracked through 500 years’ worth of records, wills and birth announcements, also linked her to Richard III’s sister. It was because of that DNA match-up with Joy (and the distinctively hunched up deformation of his backbone) that they were are able to positively identify that skeleton as Richard’s. The Toronto Star’s account of the discovery concluded with a quote from Norm revealing that his news-hound's instincts hadn't abandoned him in retirement. “As the announcement was made, 83-year-old Norm Ibsen was thinking of Joy. ‘It meant quite a bit to her, she was a monarchist,’ he said. ‘It makes a great story’.” And in another sweet touch that put the cap on this tale of the final untangling of a historical mystery, Joy and Norm’s son, Michael, a cabinet maker in England, was able to personally build the casket for Richard III’s re-interment. Mooching around through stacks of new arrivals at Attic Books one afternoon in May of 2015, and finding volumes by G.A. Henty, G.K. Chesterton, Penelope Fitzgerald (her incredibly rare biography and compilation of poems by the all but forgotten Charlotte Mew) and miscellaneous titles by the earlier mentioned White, Thurber, Baring and Kingsmill, I impressed the hell out of their sales staff by intuiting, “You must’ve just bought this lot from Norm Ibsen. Is he okay? Tell me this isn’t an estate sale.” Norm was still with us, they assured me, but he was scaling back his collection in preparation for moving out to B.C. to be near his daughter. A group of Norm’s old colleagues and friends threw a going away party for him at Chaucer’s that September and that was where I learned that Norm was moving into a beautifully appointed retirement home in the coastal town of Sidney which boasts a population of 11,500 souls and twelve (count ‘em, twelve) thriving used book stores. My own daughter had shrewdly taken me there the year before when I visited with her on Salt Spring Island on my way home from Australia. (Daughters are so wise, aren’t they?) It seemed that Norm had found his Shangri-La but after a couple of years that home was snapped up by a larger, cheese-paring conglomerate which cut back on all manner of civilizing amenities and started serving up perfectly hideous meals and Norm (perpetually slim, I'm told he was also a gourmand) bailed out, returning to London to live out his final days at Windermere on the Mount. I never met with Norm personally after that going away party but he subscribed to this blog and I heard through mutual friends that – except for the matter of one crate of books that went missing during the move back to London and never did turn up – he was very content to be back in the city where he’d lived and worked for most of his life. And I will always be glad that Norm and I had a few minutes to ourselves at that very well attended party when I was able to thank him for doing so much to help me find my way.

3 Comments

8/6/2020 09:15:49 am

Thank you Herman for this moving and very personal tribute to a great Londoner..

Reply

Mark Richardson

8/6/2020 12:43:25 pm

Thank you for a touching and impressive 'blog, this morning. I only met Norm Ibsen the day his son spoke at my Richard III event at the library, years ago, but I was impressed by Norm's quiet goodness, even then.

Reply

9/6/2020 09:38:21 am

This is a fine tribute to Norm Ibsen--and, so, a good Goodden contribution once again to personal and local history--and it has the added news that the genes of a London, Ont. personality led to the identification of the remains of King Richard III and that, amazingly, one of her sons constructed Richard's new (and last) coffin.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed