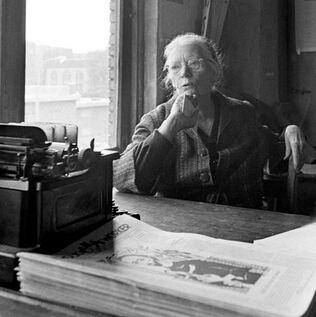

Dorothy Day (1897 – 1980) Dorothy Day (1897 – 1980) LONDON, ONTARIO – One of the unlikelier candidates for sainthood which the ages have offered up, the American writer, pacifist and activist Dorothy Day (1897–1980) shacked up with a series of men in her twenties, had a baby aborted, rebounded into a rather cynical marriage that didn’t even last a year, bore a child out of wedlock, was once a card-carrying Communist, spent an unfortunate amount of time in jail for acts of civil disobedience, and was the subject of a 500 page FBI file. Ordinarily the Church finds it advisable to give departed Catholic figureheads at least a century to cool down before risking canonization. It’s hard to imagine any further scandals will emerge about Day's private life or her politics, but a century’s grace period will be useful for shedding any faddish aspects of her reputation. While Pope Francis always chats her up enthusiastically for American audiences and New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan has begun the phase of gathering evidence for her cause, I wonder how compelling her example will be when the last of the flower children – who saw her as a piously protesting prototype – has passed away. I was initially excited to see an interview with Day on an old episode of William F. Buckley’s Firing Line that was posted on YouTube but ultimately found her kind of hectoring and boring. Also posted on YouTube is a pretty decent 1996 film based on her life, which does a much better job of capturing her appeal. Starring Moira Kelly, Martin Sheen and Brian Keith, Entertaining Angels. was filmed on the proverbial shoestring but its only grating elements are Martin Sheen’s appalling French accent and an over-reliance on (yawn) Amazing Grace for musical uplift. The daughter of an itinerant sportswriter, Dorothy was blessed with a gift for words. Revering the writings of Jack London and Upton Sinclair, she immersed herself in labour history and revolutionary theory and landed her first reportorial job with The Call in 1916. This New York Socialist daily published her interviews with birth control advocate Margaret Sanger and Leon Trotsky, then in exile from the Russian revolutionary government. From there she graduated to The Masses where she worked, shoulder to shoulder, with Max Eastman and John Reed and after that paper was suppressed by the government, she fell in with the bohemian set of Eugene O’Neill and was his constant companion for well over a year. At this same time she became a secret Bible reader and would slip into churches whenever she could do so unnoticed. Though her parents were religiously indifferent, some neighbouring Methodist and Catholic families had awakened an instinctive sense of piety in the young girl; a deeply nourishing “sense of the sweetness of faith” which would haunt her all through her early adulthood while she searched for community and love in all of the wrong places. It was the Roman Catholic faith which drew her most strongly and she was terrified of what her friends in the movement would think should she accept its precepts. Hadn’t Marx himself declared that the Church was ‘the opiate of the people’? With the proceeds from an early novel, The Eleventh Virgin (“a very bad book,” she said of it later) Dorothy bought a bungalow on the beach of Staten Island where she lived common-law with an English biologist, anarchist and atheist, Forster Batterham. Their few years together were among the happiest of her life. His enthusiasm for the marine and plant life all around them was a joyful revelation for Dorothy who’d spent all her years kicking around in the man-made debris of inner cities, and her heart opened up in a whole new way to the beauty of the world and God. She was surprised and secretly delighted when she became pregnant for the second time - she feared that her earlier abortion had rendered her barren - and was determined to keep and raise this child no matter what. It was the experiences of pregnancy and childbirth that ultimately compelled Dorothy into the Church. “No human creature could receive or contain so vast a flood of love and joy as I often felt after the birth of my child," she wrote. "With this came the need to worship, to adore.” Those decisions were a double whammy which terminated her relationship with Batterham who rather ridiculously believed it was quite all right to impregnate women but that it was immoral to bring children into this world. In his feckless self-absorption, Batterham was a bit of a precursor of the male hippie and experienced no apparent moral or conscientious difficulties in abandoning his lover and child to fend for themselves. For five years Dorothy struggled to raise her daughter on the occasional wages of freelance journalism but always felt there must be something more she could do; some activity which would fuse her faith and her talent, her pacifism and her social activism, into some higher calling. In her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, she writes about attending a demonstration of the unemployed in Washington D.C. and then dropping into a church: “There I offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.” Returning home to her New York apartment, she found a disheveled little man waiting on her stoop. He’d been given her address by a mutual friend who told him that he and Dorothy thought alike. This was Peter Maurin, an itinerant French philosopher/peasant, and within a year this unlikely pair started up the greatest lay apostolate in the history of the United States. Dorothy served as editor and publisher of The Catholic Worker newspaper for the next 47 years. It is still published today, still sells for a penny a copy and is still distinguished by a bounty of superb woodcut illustrations that the artist, Fritz Eichenberg, donated to the paper. Eventually there were more than fifty Houses of Hospitality and farming communes all across the United States where the destitute could be fed and clothed and housed and where workers and intellectuals could gather for discussions. In his biography of Dorothy Day, Love Is the Measure, Jim Forrest writes: “More remarkable than the providence of their meeting was Dorothy’s willingness to listen to Peter Maurin. To many others he would have seemed just one more street corner prophet . . . Yet Dorothy gave him not only patient but increasingly appreciative attention. He wanted to look at history in a new way which centred not on the rise and fall of empires but rather on the lives of the saints. He was certain that sanctity was at the centre of what really mattered and that any program of social change must emphasize sanctity and community.” For the rest of her life Dorothy’s home base was in the Catholic Worker House on Mott Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side where she lived with the poor she served, engaging in all the routine and disagreeable chores of the house, and writing only in her spare time. What most distinguishes the Catholic Worker movement from any other kind of social agency or network, is this matter of the workers’ engagement, their full, 24-hour a day immersion in the poverty they seek to relieve. In Loaves and Fishes, her personal history of the Catholic Worker movement, Dorothy writes, “Poverty is a strange and elusive thing . . . I condemn poverty and I advocate it; poverty is simple and complex at once; it is a social phenomenon and a personal matter.” Psychologist and writer Robert Coles met Dorothy for the first time at that Catholic Worker House. He was stealing time from his medical studies to go and see her and was anxious about some personal uncertainties regarding his chosen path in life; an existential quandary which was pumped up even higher when a well-dressed woman dropped dead on the sidewalk just in front of him and he was utterly powerless to help her. Badly shaken by the time he got to Mott Street, Coles was driven half mad while waiting to speak with Dorothy by an incoherent drunken woman with a huge birthmark on her face who wouldn’t stop talking and monopolizing Dorothy’s attention. “Finally, silence fell upon the room,” he wrote. “Dorothy asked the woman if she would mind an interruption. She got up and came over to me. She said, ‘Are you waiting to talk with one of us?’ “One of us: with those three words she had cut through layers of self-importance, a lifetime of bourgeois privilege, and scraped the hard bone of pride.” In his introduction to a posthumous collection of Dorothy’s writings which he compiled, By Little and By Little (which I would deem the best single volume for someone who wants to see what Dorothy Day was about) Robert Ellsberg states that, “It was not what Dorothy Day wrote that was extraordinary, nor even what she believed, but the fact that there was absolutely no distinction between what she believed, what she wrote, and the manner in which she lived.” In my opinion her best writing is to be found in her Catholic Worker columns which were scribbled on the fly while putting together the paper, organizing and speaking at meetings, and feeding, clothing and accommodating the never-ending stream of homeless people. Dorothy’s finest literary gifts – a sharp eye and an intuitive daring - were decidedly journalistic. Whenever she had more time to work on a project, a ponderous, self-conscious earnestness creeps in and the proceedings get a little leaden.  Her spiritual director at one point in her life advised her to compose a biography of St. Therese of Lisieux. One can imagine what prompted that assignment. 'Let's see if I can get this gifted writer to set aside the politics and the angst for a bit and contemplate instead the guileless character of a cherubic, well-born saint who was popularly known as The Little Flower.' Dorothy practically had to chain herself to her desk, sighing in exasperation and grinding her teeth as she labored in bursts to bring forth this dud of a book which – thankfully – is very hard to find. Toward the end of her life Dorothy started to receive accolades from farther afield than the radical wing of the Church. At the age of 75 she was given an award by the University of Notre Dame for “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, virtually all her life.” She wished her work wasn’t seen as exceptional and had little patience with awards and talk of sainthood. She felt that people were denying a similar capacity in themselves when they set her apart as special. “Don’t call me a saint,” she said in what became her most frequently cited quote. “I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” And again, there’s that grudging and oddly graceless note. A sense of unworthiness I could have understood but this feels more like resentment; almost like pouting, because her sacrificial example of service to others hasn’t inspired more people to throw over the trappings and routines of their lives to join her in the trenches of social justice. And who are these supposed Catholics who dismiss their saints too easily? But when you read her more incidental columns, that's when Dorothy Day comes down off her high horse of martyrdom and casts a more gracious and compelling light on the human predicament. You can smell the pot of soup boiling away on the stove, feel the cold draft as the next shift of diners comes in the front door, hear the phone ring as Macy’s calls for someone to come around and pick up some leftover cafeteria food. And all these distractions are not distractions – they are the whole point. This is what it means to live your life as if you were your brother’s keeper; to find Christ and minister to Him by serving the needs of the poor; to treat these forgotten people as if they were ‘one of us’.

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

25/6/2021 11:25:24 am

In many ways an excellent summary of her life Herman. Not even too judgemental. But why did you not honestly place her within the historical context of her times. I doubt many of your readers know anything about the extent and depth of degradation, poverty, starvation, exploitation and abuse the poor suffered in19th and early 20th century America. At the bottom of the pile along with the liberated slaves were the Catholic immigrants. They were later joined by the Jews. A man to stand up criticize and challenge the status quo needed courage, strength of will and, if you like, a boundless faith. A woman, ten times as much.

Reply

Gene B

13/10/2022 08:25:28 pm

I was directed to this essay by Phil Runkel.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed