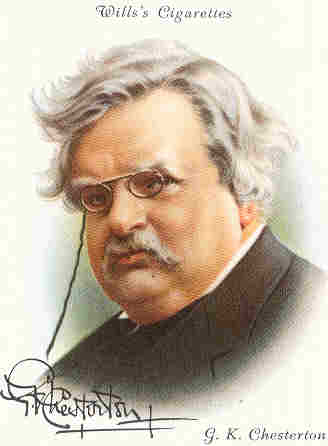

Alastair Sim as Ebenezer Scrooge Alastair Sim as Ebenezer Scrooge LONDON, ONTARIO – December is the month when even people who do not read and ordinarily display no love for the classics, are apt to bump into one of the dozens of film adaptations (or variations thereupon) of Charles Dickens’ (1812–70) single best-known story; his short novella from 1843, A Christmas Carol. And if they’re particularly lucky, the version of this preternaturally powerful parable which they’ll latch onto, is the 1951 production directed by Brian Desmond Hurst and starring Alastair Sim as Ebenezer Scrooge. This version is the truest to the original story, quoting great slabs of glorious Dickensian dialogue verbatim, and also spares its viewers the squirm-inducing misery of having to navigate or ignore any extraneous musical interludes of larded-on piety and sentiment. While it would be a shame if the only Dickens story one knew was A Christmas Carol (there’s so much more to explore!) even that limited reading or viewing would be sufficient to establish a fair idea of the author’s gifts and strengths. Seven years ago the English-speaking world celebrated the bicentennial of Charles Dickens’ birth, according him accolades second only to William Shakespeare for sheer fecundity in the service of literary genius. Not so widely acknowledged at that time was the impact of the great Catholic writer and apologist, G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936), in framing our understanding of Dickens. Chesterton’s acclaimed biography of Charles Dickens was published in 1906 when Chesterton was 32 years old, and had already tackled biographies of the Victorian allegorical painter, G.F. Watts and the poet, Robert Browning. Most recently he had published Heretics, a book-length ethical and philosophical dispute with most of the influential writers of the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Notable among the few literary heavyweights he did not do battle with in that splendidly vituperative tome was Charles Dickens. Today a literary ‘biography’ will usually include a fair amount of material recounting its subject’s life. This was not the tradition in 1906 when a life’s story would be very lightly sketched and most attention would be paid to a writer’s books. It might be closer to the mark to call Chesterton’s book a ‘critical study’ though even that term would mislead, suggesting as it does a level of objective detachment which the ever-exuberant Chesterton never wielded in any of his writing. It might be truest to call it a ‘celebration.’ The value of all of Chesterton’s biographies, and particularly his Dickens, wasn’t so much their biographical veracity – the strokes were much too broad and even reckless for that – as their author’s uncanny ability to isolate and magnify the important truths about their subjects’ writing and thinking that no one had ever latched onto before. Significantly, in his own massive biography of Dickens from 1990, today’s undisputed Dickens authority, Peter Ackroyd, tips his hat to Chesterton not as a biographical precursor of importance but as “Dickens’ best critic”.  Charles Dickens Charles Dickens Early on in the book – and writing at a time when not so much was known about Dickens’ appalling treatment of his wife nor the tetchiness of his relations with his publishers and professional colleagues – Chesterton latched onto a situation from Dickens’ infancy and made it serve as a kind of template for his subject’s entire life and career. Commenting on how Dickens’ father used to get the boy to sing songs and provide entertainment for his elders, Chesterton writes: “Some of the earliest glimpses we have of Charles Dickens show him to us perched on some chair or table singing comic songs in an atmosphere of perpetual applause. So, almost as soon as he can toddle, he steps into the glare of the footlights. He never stepped out of it until he died. He was a good man, as men go in this bewildering world of ours, brave, transparent, tender-hearted, scrupulously independent and honourable; he was not a man whose weaknesses should be spoken of without some delicacy and doubt. But there did mingle with his merits all his life this theatrical quality, this atmosphere of being shown off – a sort of hilarious self-consciousness. His literary life was a triumphal procession; he died drunken with glory. And behind all this nine years’ wonder that filled the world, behind his gigantic tours and his ten thousand editions, the crowded lectures and the crashing brass, behind all the thing we really see is the flushed face of a little boy singing music-hall songs to a circle of aunts and uncles. And this precocious pleasure explains much, too, in the moral way. Dickens had all his life the faults of the little boy who is kept up too late at night. The boy in such a case exhibits a psychological paradox; he is a little too irritable because he is a little too happy. Like the over-wrought child in society, he was splendidly sociable, and yet suddenly quarrelsome. In all the practical relations of his life he was what the child is in the last hours of an evening party, genuinely delighted, genuinely delightful, genuinely affectionate and happy, and yet in some strange way fundamentally exasperated and dangerously close to tears.” Chesterton’s book on Dickens appeared 36 years after his subject’s death in 1870 at the age of 58, so the gap between their lifetimes was not unfathomably large. It would be like someone writing today about J.R.R. Tolkien or P.G. Wodehouse. Though Chesterton was born four years after Dickens’ death, in most ways, they occupied the same world. Chesterton wrote at a time when Dickens wasn’t neglected – uniquely there has never been a period of popular eclipse for Dickens – but he wasn’t yet regarded as a ‘classic’ either. The cultural overlords of the time tended to sneer at Dickens in much the same way as today’s academic and critical writers reflexively dismiss any novelist who cranks out bestsellers a little too quickly. In the years between Dickens’ death and the appearance of Chesterton’s book, the literary fashions of ‘realism’ and ‘expressionism,’ led to criticism that Dickens’ worldview as reflected in his writing was un-lifelike, that the perils his characters faced were exaggerated and their outcomes were overly optimistic. Chesterton argued that of course Dickens exaggerated but like any self-respecting artist he only did so, “when he found a truth to exaggerate. It is a deadly error (an error at the back of much of the false placidity of our politics) to suppose that lies are told with excess and luxuriance, and truths told with modesty and restraint. Some of the most frantic lies on the face of life are told with modesty and restraint; for the simple reason that only modesty and restraint will save them . . . Truth alone can be exaggerated; nothing else can stand the strain.” Chesterton also makes the salient point that “this too easily contented Dickens . . . this happy dreamer, this vulgar optimist . . . alone of modern writers did really destroy some of the wrongs he hated and bring about some of the reforms he desired. Dickens did help to pull down the debtors’ prisons. . . Dickens did leave his mark on Parochialism, on nursing, on funerals, on public executions, on workhouses, on the Court of Chancery. These things were altered; they are different . . . If Dickens was an optimist he was an uncommonly active and useful kind of optimist.” Indeed, it would not be taking things too far to claim that we owe to Charles Dickens and A Christmas Carol in particular, this sense we all have that one’s Christmas hasn’t been properly observed if the benevolence and generosity of the season isn’t in some way extended beyond our own front doors. In many ways Dickens was the great progenitor of what we think of today as social justice, and he understood a principle that many advocates for the poor seem to have forgotten; that appeals to assist the less well-off are unlikely to succeed (except with pathologically self-hating liberals) if they are only driven by recriminations, accusations and claims of entitlement and not by appeals to one’s better nature. Chesterton points out the rare and mystical balance that Dickens achieved in his books which is key to awakening any sustainable drive for social assistance or reform. “If we are to save the oppressed, we must have two apparently antagonistic emotions in us at the same time. We must think the oppressed man intensely miserable, and at the same time intensely attractive and important. We must insist with violence upon his degradation; we must insist with the same violence upon his dignity. For if we relax by one inch the one assertion, men will say he does not need saving. And if we relax by one inch the other assertion, men will say he is not worth saving.” Chesterton’s biography of Dickens was an enormous commercial and critical success which, one typical review of the time said, “marks the definite entry of its author into the serious walks of literature.” The book not only established Chesterton; it re-established Dickens on a higher plateau as marked by the publication the very next year of the Everyman editions of Dickens’ entire oeuvre, with specially commissioned introductions by Chesterton to all two dozen volumes. In 1911, all of those introductions were gathered together in the book, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens. It too, is well worth reading. But for the thrill of witnessing the splendour of one great writer coming into his own in the act of appraising the greatness of another, start with 1906’s Charles Dickens.

1 Comment

Max Lucchesi

10/12/2019 11:12:15 am

I admit I have read very little Chesterton, in my voraciously avid reading days. The faith of the catholic authors I read was that of authors brought up and educated in catholic countries rather than the dewy-eyed intellectual faith of it's converts. Catholic authors who had experienced, as well as the beauty and gentleness of their religion it's brutality. oppression and hypocrisy. The Italian, Irish, Latin and South Americans who were mostly banned or pilloried in their own countries.. You are probably aware of Chesterton's view of the 'fairer sex'. That they were everything a man wasn't. Thrifty, chaste, nurturing. loyal, devout and generous. With this ideal installed on a pedestal vision in mind his opinion of feminism, "as plodding, obdurate, elephantine imitation of the male". His quote. "Boys play football, why shouldn't girls play football? Boys go to Oxford, why shouldn't girls go to Oxford? Boys grow mustaches, why shouldn't girls grow mustaches"? No doubt said in jest!! That women should be denied the vote to "keep them above the baying herd". So not quite up to our manly snuff then, or as Kipling said " a woman is only a woman but a good cigar is a smoke. So light me up another Cuban." Was G.K.C by any chance also Anti Semitic, I ask this because of his opposition to the 'Jewish bankers and their hold on the finances of the world'. Almost a quote from his friend's book "The Jews". .Why have you never shared this G.K.C with us?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed