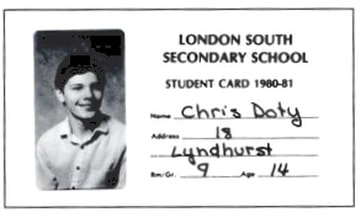

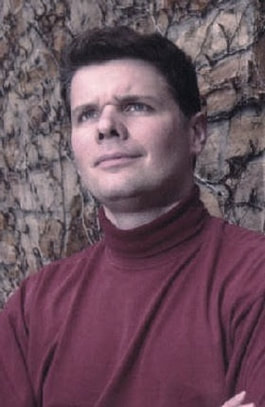

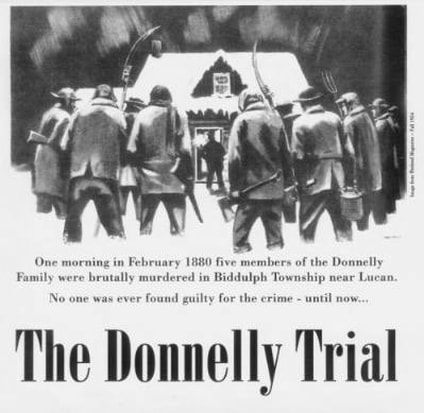

LONDON, ONTARIO – In a tip of the hat to the Forest City Film Festival which is underway (October 17 – 24, 2020) like so much else in this dispiriting year in virtual format only, I’ve gone rooting through the tickle trunk in search of two articles I wrote about the late, great London filmmaker, Chris Doty (1966–2006). The first article, a generously proportioned feature, hails from June of 1998 when London’s daily newspaper was published seven days a week. This article appeared in the Londoner section of the Sunday edition of the London Free Press; a section which Chris contributed articles to almost as frequently as me as a way to supplement the modest avails of operating in London as an independent documentarian. This article ran as a sort of preview plug to his just completed history of London, Vagabonds and Visionaries; a film which can be seen today in its entirety on YouTube. A WITTY AND TENACIOUS advocate of forgotten characters and lost causes, documentary film director Chris Doty has always had the confidence or the nerve to quietly go his own way. He made his earthly arrival in his own way too. “I was born in St. Joseph’s Hospital on September 8, 1966, an hour and a quarter before they aired the first episode of Star Trek on CTV.” Since the death of his father in 1993, the 31 year-old filmmaker helps out with the domestic economy by living with his mother in the same south London home where he grew up, two short blocks east of his old alma maters – Tecumseh Public School and South Secondary School. Tooling around town on his trusty bicycle, the non-driving Doty cuts an inconspicuous figure but this incisive and opinionated dynamo is earning a national reputation for some first rate documentaries which tell little known tales of the Forest City’s past. “I didn’t intend to become a historian,” Doty explains. “I actually had a horrible experience with history in public school.” When the Parti Quebecois gained power in 1976, Doty swears that his teachers began emphasizing French content in Canadian history courses at the expense of other study segments. “They thought ‘if we can just teach our students enough French history then Quebec will never leave. We’ll simply overwhelm them with our knowledge and love for French history.’ Consequently, we had all this stuff about Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain rammed down our throats. I think there was one paragraph about a certain battle on the Plains of Abraham. There was nothing about Governor Simcoe or the founding of London, nothing at all about local history.” If adolescent peer pressure couldn’t make Doty discard his quirky enthusiasm for LP recordings of Nat King Cole and Doris Day, then he certainly wasn’t going to submit to anybody else’s view of what did or didn’t constitute appropriate historical subjects. Determined to show that history isn’t just a bunch of boring dates and facts that happened to other people in other places a long time ago, Doty gave his big speech in grade seven on the Victoria Day Disaster of 1881 when an overloaded steamboat, The Victoria, capsized in the Thames River northeast of Springbank Park, killing an estimated 180 passengers, mostly Londoners. It is said there was scarcely a single London household at the time which didn’t lose a relative, friend or neighbour. Ever the archivist, Doty still has the tape recording of that speech. “I was twelve years old so my voice hadn’t broken yet. It makes for pretty painful listening.” Despite his nervousness, Doty detected an almost vicarious reaction in his classmates to all the local references in his speech. One by one, he could see the little light bulbs over their heads switching on. ‘Hey, he’s talking about something that actually happened here.’ Doty sees the same sort of illumination gradually dawn on viewers of his films. “I’ve always believed that Londoners are interested in their history,” Doty says. “But you have to find the right medium to really get to them. We live in the so-called ‘information age’ which I think is a load of crap. The last thing people want is more CD-Roms full of Canadian history. What people want is strong storylines told in a compelling way. You have to present characters in gripping situations and mix all that with the right kind of visual material.” Doty graduated from the journalism program at UWO in 1991. Whether he was developing stories for print, radio or TV, Doty was particularly drawn to local historical subjects. His 20-minute student documentary on the old Palace Theatre (a long time movie house on Dundas Street East which was then being refurbished as the home of the London Community Players theatre troupe) was sufficiently impressive that the folks at Maclean Hunter Cable TV gave him project funding (but no salary) to put together his first post-graduate film. Marc Emery: ‘Messing Up the System’ premiered on the cable channel on September 22, 1992, though it was eventually pulled from their schedule following viewer complaints about vulgar language and controversial subject matter. Telling the life story of the strident marijuana advocate and libertarian activist who was just then emigrating to Thailand because he was fed up with stodgy old London, Doty’s first feature documentary couldn’t help but upset some viewers. Today, it remains the only one of Doty’s films not available on video through the London Public Library. Edgy, provocative, wickedly funny in spots, Doty’s first documentary was a revelation for London TV viewers who’d never seen local stories handled with this kind of flair. “I just shudder at some of the things we did in that documentary,” Doty admits today. “Shooting photos off of newspapers, using VHS tape dubs of television broadcasts - I wouldn’t dream of doing stuff like that now. But I’m still damn proud of that documentary. I think it’s one of the three best things I ever did. Everyone wants to forget about that one except me.” The Emery documentary was seen by Merle Zoerb who was the head of programming for Maclean Hunter. He liked it and gave Doty his first paid assignment, making a documentary on Fred Metcalf, the founder of Maclean Hunter Cable TV. With more money to acquire better production standards, Doty saw the making of this corporate video and a couple later assignments as his technical apprenticeship. “With Emery I showed that I knew how to do content and how to write it. The next few documentaries allowed me to polish my style and to realize different kinds of pacing, to use proper visuals and get the best quality material for the documentaries.” All that would come in handy later. But first of all, Chris Doty’s world had to fall apart. “We were going in to record the narration on the afternoon of March 31st, 1993. I’d come home from Western after looking at some photographs and there was a police officer at the front door and he had news that my father had been in a car accident and had been killed.” Doty pauses to collect himself. “That was easily the worst day of my life. The reason why I’m telling you all this . . . my father was an insurance agent all his life but he was a frustrated historian at heart. He always told me that if he had his life to live over again, he’d make sure he went to college or university and properly study history. His family just didn’t have the money back in the ‘40s and he had to start working at a very early age.” With an affectionate smile, Doty recalls, “My dad was a big Civil War buff. This was a man who took his wife to Gettysburg on his honeymoon – that’s the type of guy he was. I went to Gettysburg with him in ’91 when I got out of journalism school and we had a great time. I loved listening to him because he was just so knowledgeable about it all. And he still wanted to go back again.” And here’s the kicker. “I’m pretty sure that he died a frustrated man. He was only 65. He had just retired and had he lived I’m sure he would’ve delved more and more into his love of history. With my father’s death I realized the importance of not sticking with a job because it pays well. I knew I wasn’t going to be one of those guys who turns 40 and says, ‘Gee, I wonder what would have happened if I’d ever given that a try?’ I learned that you shouldn’t pile up all your dreams in the hope of a second act – because you might not get it.” In July of ’94, Doty resigned his day job in the circulation department of the London Free Press and started work on the documentary which would first bring him to the attention of many Londoners, Slippery. Even though Maclean Hunter was being taken over by Rogers, Merle Zoerb still had some production funds left in the kitty. “Merle called me up one day and he said, ‘Ah, Chris, Earl Catchpole (who was the program manager in London) tells me you’re working on this thing about a walrus or a lion, is it?’ I said, ‘No, it’s about a sea lion,’ and started explaining it. And he said, ‘This sounds good to me, Chris. Here’s $5,000. Go to it.’ It was the easiest bloody funding I’ve ever had in my life.” Doty regarded Slippery as the culmination of all his work to that point; something which would show the new cable station owners just what could be done in the field of local documentaries. Using footage from old home movies and newsreels and conducting contemporary interviews with a dozen subjects in London, Toledo and Sandusky Ohio, Doty told the fabulous tale of a brave California sea lion’s escape from Storybook Gardens in 1958. Heading out on the lam a week before the zoo’s official opening, Slippery eluded capture for eight long days as he went snaking through the waterways of south-western Ontario and the neighbouring states, monitored all the while by massive international media coverage. Slippery won two first prizes in Canadian and Ontario broadcasting festivals but all the same, Doty’s career as a filmmaker was suddenly stalled. “I sweated my heart out over that film, just really trying to do this whole thing up well. And absolutely nothing happened. Rogers bought out Maclean Hunter and all my contacts dried up overnight. By the spring of ’96 I realized this was all going nowhere. Rogers wasn’t interested in any of my proposals. I had half-heartedly started sketching out a script on the flood but put it aside thinking there must be more commercial things to get into and was forced to take a job at the Strathroy Age-Dispatch. I had to do something to make a living.”  CHRIS DOTY ( 1966–2006) CHRIS DOTY ( 1966–2006) Doty really believed that he was walking away from his “erratic, so-called career as a documentary filmmaker” but life had other plans. “It was like the hand of God poking through the clouds and setting me back on the right path,” he says about a 72 hour sequence of events that fall. First, Andy Robinson, an eager young pup just out of high school, came up to him at a party and said he really wanted to work on a documentary with him. “Aren’t you working on something about the flood?” he asked Doty. “I can do camera work, produce . . . anything.” Three days later Doty was dumped by an unreciprocated love interest who took him to C. Ross Park in Broughdale to drop her little bombshell. “Broughdale was the first part of London to succumb to the flood of 1937,” Doty explains. “She just wanted to be friends, she told me. The Aubrey Fetterly house was just across the way from the park. That’s the place that had its whole front wall torn off in the flood and I’m staring at that, thinking, ‘Wasn’t that joint torn down? I could use that in the film. If I was making a film.’ I had my charming Alaskan malamute, Tiki, with me that day, and went for a walk to clear my head and she somehow managed to fall into the river and I had to fish her out. It was uncanny how everything was conspiring to make me think about the river and the flood.” Feeling that he badly needed some sort of project to pull his life together, Doty called Craig Cole, the program manager at Rogers, and offered to make the flood documentary for nothing if they’d pay for all the film stock transfers, the photo enlargements and also hold a premiere for it. Cole agreed and work started on Lost April: The Flood of ’37, one week later. The film’s total budget Doty estimates at $750. “It was the luckiest project I ever worked on,” Doty says. Everything just came together. From getting Max Ferguson to share his stories of the flood, to finding more film footage than anyone dreamed existed, to getting these great photographs out of the Free Press that no one had seen before. Our premiere was held on the 60th anniversary so this was going to be the last chance to get a lot of these great stories from the people who went through it.” Lost April (Doty copped the title from a Nat King Cole record) won the big national prize for documentaries at the Galaxi Awards for Excellence in Programming. With interest goosed by the flood in Manitoba last spring, Lost April was broadcast by cable channels across the country and was optioned by Vision TV and the History Channel. Locally the documentary was received with almost religious significance – particularly by the flood’s survivors. One of the questions most frequently asked of him was, where on Earth did he find the footage of rats fleeing London West just before the deluge? “No one thinks film footage exists of London before 1950 but there’s reams and reams of it out there. I knew about the footage that a guy named Charlie Ford had shot and that had been excerpted in a CFPL broadcast from 1987. I got hold of a really lousy video copy and was trying to track down the original footage and was told, “Oh, you’ll never get that because the Ford family is very protective of it.” Charlie Ford had since died and the footage had passed on to his son, Bob Ford, who was a very good friend of my father’s and when he found out who I was, it was no problem. This is what I mean about getting lucky with this project. And then when I saw the footage of the rats leaving London – I couldn’t believe that CFPL didn’t use that segment.” The Rogers brass were sufficiently impressed with Lost April that they readily funded Doty’s next project, Vagabonds and Visionaries: The London Story, which premiers this Thursday night on Rogers Community TV. “For the very first time, I had a decent budget. About $25,000. It approximates a job. It’s enough to live on. Being able to go to CFPL when I want to use their film footage and pay to have it transferred to video – this has been a real novelty for me.” Unlike his earlier films which have zeroed in on individual characters and events, Vagabonds and Visionaries gives an overview of London’s 205 year history in 90 minutes. “I got lots of advice about what I should cover but when push comes to shove, it’s me in the editing suite with my editor calling the shots. If it doesn’t feel right to me, I’m not saying I won’t put it in but you’re going to have to persuade me. I see the model for this film as Noel Coward’s Cavalcade. You’re zipping through history focussing on some people in the foreground and trying to fit as much interesting material into the background as you can. But it’s very much a panoramic sort of story.” Doty was surprised to find the ghost of London writer and historian Orlo Miller (1911–94) perched on his shoulder while working on his newest documentary. “Academics deride him as a blood and thunder writer who churned out cliché upon cliché but Orlo and I are essentially trying to put the ‘story’ back into history. When I go to the library and see students doing research on projects, I constantly see Orlo’s books on tables. I don’t see anything by Fred Landon or Sherwood Fox – and these guys have schools and libraries named after them but there’s nothing named after Orlo. He’s the Greek chorus throughout the whole film. He keeps popping up here and there. We open up the documentary with Orlo talking about his play, This Was London from 1955. And that’s what I want to establish right up front. Don’t expect this to be academic. We’re not going to list every single date and fact for you. We’re here to tell you the story of a city, about the people who developed it and made this city what it is today and how that city changed them as well.” Doty maintains that our most interesting ‘vagabonds and visionaries’ have been people who saw something unique in London and have worked to cultivate that uniqueness. “What would have happened if John Graves Simcoe had arrived here and said, ‘I’d like to put a capital here but Lord Dorchester might not like it, or I’d better check with the people back in England on this?’ Simcoe walked in and said, ‘I don’t care if the river peters out into nothing after Thamesville – this is the place for me.’ If Simcoe hadn’t done that, we wouldn’t have had the capital located here, we wouldn’t have had the military garrison stationed here because of the rebellion, we wouldn’t have had merchants following to cater to the soldiers stationed here, and we wouldn’t have had the railroad. And all that stemmed from one guy saying, ‘Sod it all – this is where I want the capital and I don’t care what anybody else thinks about it.’ “And I see flashes of that same spirit carrying through the entire documentary – certainly with George Wenige and his tireless campaigning, with Adam Beck riding roughshod over the interests of private power companies, with Greg Curnoe turning his back on the Toronto art scene to see what sort of scene he could encourage here, with Jane Bigelow slowing down development and building London’s first free-standing art gallery.” Doty’s biggest regret is that his dad’s not around to see his newer work. “He watched a bit of my Marc Emery documentary but he was one of those who just thought Emery was a blowhard and he couldn’t watch very much of it. I know he would have liked the more recent films more.” After the premiere, Doty plans to sleep for a week and get in some heavy duty bicycling to clear away any tensions left over from his latest project. Then he’ll start to contemplate the next one. He’d love to do a history of the Blackburn family or flesh out a few of the figures featured in Vagabonds and Visionaries. “I’m not kidding myself by thinking that this is going to be my big break and it’ll be smooth sailing from now on. I thought that with Emery and Slippery and basically ended up flat on my back. There will be another one after this and another one after that.” For anyone who enjoys seeing London stories told with style and wit, that’s very good news indeed. (Originally published in the Londoner, the London Free Press, June, 1998) And this second article from the winter of 2006 is my obituary of Chris, written in the immediate wake of his suicide by hanging. WITH THE SUICIDE on Friday, February 3rd of filmmaker, historian, writer and playwright, Chris Doty, one of London’s very brightest cultural beacons has been cruelly extinguished. Those of us who were his friends have been left grappling with cold air as we try to identify what possible misery it was that drove this most conscientious keeper of all kinds of arcana and lore to so recklessly throw away life itself. Chris’s life appeared to be on a roll. Or at least his career was. He’d carved out for himself an utterly unique niche as a freelance historian, unaffiliated with any school, and an independent filmmaker whose specialty was local stories, vividly and wittily told. His newest play (Citizen Marc, written with Jason Rip and based on Chris’s 1992 documentary, Marc Emery: Messing Up The System) was still on the boards. At its gala opening, exactly one week before he hanged himself, Chris played a roomful of media, dignitaries and guests like a fiddle, effecting introductions, providing quips, making the wheels of public relations spin and sing.  With that play’s closing the following night, Chris would not have been left twiddling his thumbs. Next up was a revival of his wildly successful play, The Donnelly Trial, comprised entirely of court transcripts regarding the unsolved 1880 massacre of a Lucan area family; unwieldy documents that Chris had brilliantly edited down into dramatic form. Generally lurching from one barely funded project to another, Chris joked that he hoped annual re-stagings of his Donnelly play could become to London (and his own cash flow) what the musical, Anne of Green Gables, was to the tourist trade of Prince Edward Island. The financial success of The Donnelly Trial seemed to give Chris the idea that his best work could be done in the theatre. But I believe the Donnelly project was a bit of a fluke. It made for a riveting entertainment largely because it was a true story. The compilation of its script engaged Chris’s uncanny gifts for burrowing through archives, plucking the most pertinent material and arranging it in a compelling sequence. These were the very same gifts he employed even more effectively, I believe, in his real medium - documentary filmmaking. While the Emery play generated masses of publicity, reviews and attendance were less than stellar and his disappointment in that reception undoubtedly contributed to the depression he was suffering. I worked with Chris in one capacity or another on five of his films. For those where I was featured as an interview subject, Chris didn’t actually provide direction, though he did what he could in couching certain questions to get the sort of material he was after. "What I want next," he told me once between intervals of filming, "is one of those ' now- get-out-of-town’ quotes." "A what?" I asked him. "You know. It’s like a zinger of a quote that completely ties up one section and bounces us forward to the next section." Over the last few days I’ve wondered again and again if Chris would still be with us, if he might have risen to greater heights and rewards and confidence, if he had been so constituted that he could ever have managed to ‘get out of town’. As one who largely shares that London-tethered constitution with Chris, I almost feel like a traitor for asking the question. But there it is. There are all kinds of artists in London, like Chris, who uniquely draw their inspiration from this place and only this place. Subsequently, their works of creation may not travel all that well and London by itself simply is not enough to support them. Chris’s brother Grant has told me that there are plans to take the profits from this year’s staging of The Donnelly Trial to establish an annual award to fund artists working in any medium who tell us something about London. I can’t think of a more fitting memorial. Chris was never one to dump his troubles on you or burden you with his woes. How one now wishes he had been inclined that way just a little, if only to have given his friends a fighting chance to dissuade him from his final appalling decision. While he maintained a gentlemanly demeanour, he was no cold fish. If you looked at all closely, you could see emotions and uncertainties burbling away just under the surface. But somehow one (or at least I) never felt invited to probe or pry. Except once, in 1998, when I interviewed him for a feature article just prior to the premiere of his 90-minute history of London, Vagabonds and Visionaries. On that occasion, I got to ask him anything, and I distinctly remember two reflections that brought him to the brink of tears. The first, quite understandably, was recalling the 1993 death of his father in a highly suspicious car accident with a tree – an accident that looked a lot like suicide. "He had just retired," Chris told me. "And had he lived, I’m sure he would’ve delved more and more into his love of history. With my father’s death I learned that you shouldn’t pile up all your dreams in the hope of a second act – because you might not get it." The second and more intriguing occasion for tears – and one that visibly surprised him, so that he shook his head in exasperation at his weakness – occurred when he got talking about London historian Orlo Miller (1911–93). Chris deeply admired Miller for his knack of "putting the story back in history," of writing books that people actually enjoyed reading. Chris clearly identified with Miller as a model to emulate. Chris was exhausted after racing to finish Vagabonds and Visionaries. In singing the praises of this older historian who had never known material ease and was routinely sniped at by academics as a fabulist, I think Chris was shuddering a little at what might lay ahead for anyone who insisted on telling local stories in his own interesting and idiosyncratic way. In the same way that Miller wrote books that people actually wanted to read, Chris’s best work could captivate people who thought they didn’t care about London history. To see what I mean, check out his films Marc Emery: Messing Up the System, Slippery (about a certain escaped sea lion), Lost April (about the flood of 1937), or Vagabonds and Visionaries. Attend The Donnelly Trial when it’s reprised this summer or get your mitts on a copy of the script. Visit his website (www.dotydocs.com) and marvel at the wealth of London lore he posted concerning everything from big bands to (portentously enough) public hangings. Dig out the commemorative 75th anniversary book he compiled and edited just three years ago about his alma mater, We’re From South! You’ll be grateful that somebody worked with such dedication and wit to tell these precious stories before the details all evaporated. And you’ll be heartbroken that, for reasons we probably shall never understand, the teller of these tales could not find a way to continue his extraordinary work. (Originally published in The London Free Press, February 2006)

3 Comments

Jim Ross

19/10/2020 11:02:18 am

Thanks, Herman. Many lives have ended like Chris Doty's, and are later recounted in the form of a single uncomplicated string. You do Mr. Doty a great mercy by holding him in a more understanding web of events.

Reply

Kim Baker

20/10/2020 10:06:47 am

Hey Herman....Further to my message yesterday, got a chance to read your post. What an amazing fellow Chris was, and what a gift to London to have all of his films. So sad that his life was cut short. Thank you for the window into his world. I am learning so much from his work.

Reply

Scott

25/7/2021 06:54:26 pm

Hi Herman - I worked with Christopher in the mid late 90s through Rogers cable Strathroy - I produced his 5 minute segments from the Age dispatch for 'Plugged in" weekly local news show - here's one of the many examples : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BapdXVkuYk

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed