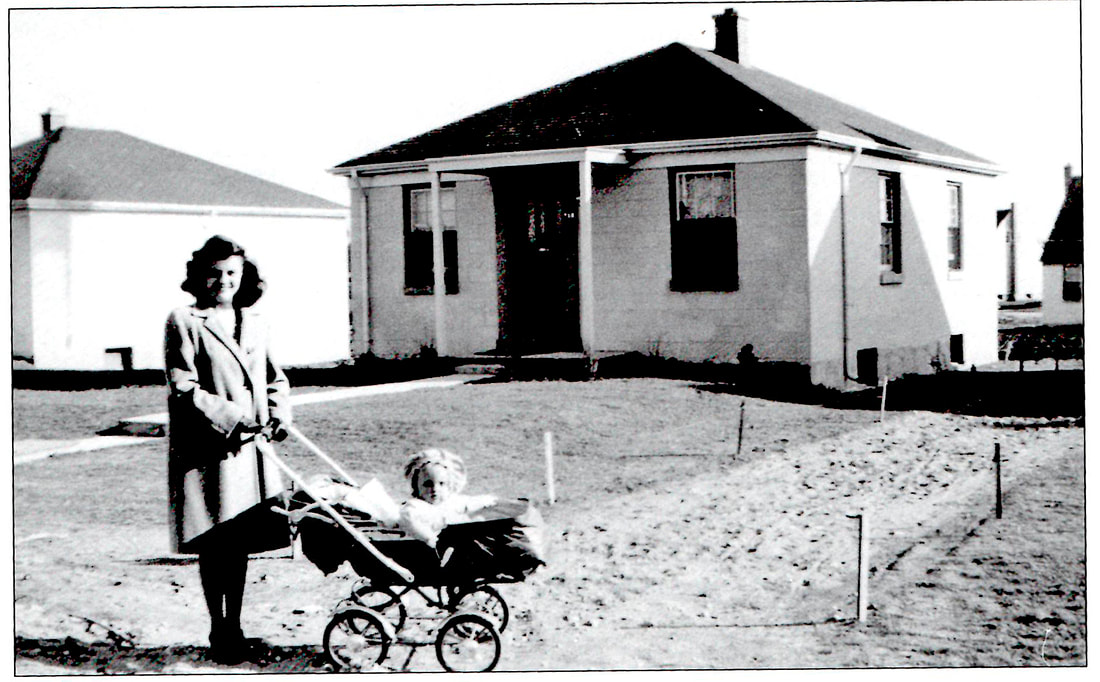

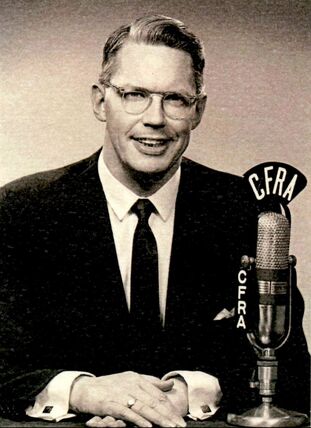

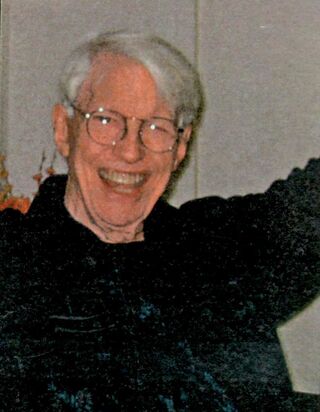

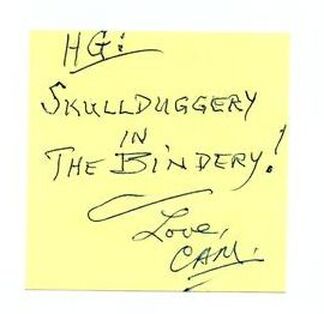

G. Campbell McDonald with his CCM Bluebird (1934) G. Campbell McDonald with his CCM Bluebird (1934) LONDON, ONTARIO – Back in June of 1995 when I was editing SCENE magazine and my wife was doing the layout, I turned a review of Susan Wallis’ just-released book, Bicycle Day Trips in and Around London, into a full-length column which I entitled Recovering the Thrill of Messing Around on Bikes. Wallis’ book had inspired me to drag the Raleigh ten-speed which I had been ignoring for almost 20 years out of our garden shed and take it for a spin. It was then I realized how much I’d never liked that bike and how much I preferred the old one-speed coaster bikes of my youth which didn’t require me to crouch forward in a way I found unnatural and uncomfortable. Then, remembering the previous month’s celebrations of the 50th anniversary of VE Day when a whole phalanx of wooden-clogged Dutch-Canadians rode crepe-decorated coaster bikes down Dundas Street as part of a glorious parade, I dropped into To Wheels to see if such a straightforward cycle could still be had for love or money and went zooming out of there ten minutes later (and $199.98 lighter) on a blue Raleigh one-speed with coaster brakes and a commodious seat and upright handle bars – just like God intended. In one impetuous trice I was smitten with biking all over again and the essay I dashed off for that week’s issue was a giddy hymn to the rediscovered joys of simple mobility. I was delighted a couple days later when one of my most encouraging and faithful readers, Cam McDonald, submitted a typically elegant and winsome letter to the editor for our next issue: Ah Herman . . . Bard of the Bikes! Sure, it was like hearing the lilt of a harp as you strummed your ballad of praise on the spokes of your new bike. There’s no such writing to be had anywhere else, I do declare. Your words rode me back to one of my most vividly happy years when I turned 13. My dream cycle was a Royal blue, shiny new CCM coaster of the classic series that spanned the 30s, 40s and 50s. Before even a scratch should mar an inch of her, I half-pushed, half-carried her up a long narrow flight of steep wooden stairs to a photographer’s studio for a formal portrait of Bluebird and me. Still have it in my album of tinted memories. Has your baby been christened yet? And there, prominently displayed in the foyer outside the modernist chapel of St. Gabriel’s Passionist Parish in North York where Cam’s funeral mass was held last Thursday, was the legendary photo of one deliriously happy boy and his brand new bike. And in that photo and all the others pinned onto three bulletin boards, was confirmation that this irrepressible man had always been a most exuberant smiler throughout the 98 years of his earthly sojourn. Riding the pre-dawn milk train into Toronto that morning, I kept getting yanked out of the book I was reading to give myself over to recollections of the man whose passing I was en route to mourn. I remembered the summer afternoon in 1993 when he introduced himself to me at a London Tigers’ ball game. I initially wondered if this beaming 72 year-old cherub – asking to take my picture, for goodness’ sake – could possibly be for real. Of course one is naturally predisposed to like anyone who says they love your writing. And whatever residual qualms I retained soon melted away as we fell into conversation. This most un-wretched looking man had himself been an ‘ink-stained wretch’ back in the day but had somehow made it into his dotage without losing his curiosity and still sought sustenance by reading every newspaper and magazine he could lay his hands on; be it local, national, international or extraterrestrial. Having made my acquaintance, Cam immediately began inundating me with his regularly dispatched manila envelopes that were covered in rows of low-denomination stamps and crammed with clippings that he thought might pique my amusement or inspire a column. Concerned that I wasn't getting enough slander and gossip in my literary diet, that Christmas he gave me the first installment in a perpetually renewed subscription to Frank magazine so that I could keep tabs on the low behaviour of the high and mighty, I recognized that this was a man who knew an awful lot about everything and Cam quickly became indispensable to me as a savvy and reliable source of information and tips and as someone to bounce ideas off of when I was working up certain articles or projects. Though we both were practicing Roman Catholics, shared a love for well-turned prose and a respect for the community-binding powers of a fair and diligent press, I pretty well understood from the get-go that Cam intuitively skewed in a more socially liberal direction than me. (In truth, I meet very few people in this life who don’t.) I remember gaping at him incredulously when he announced prior to a municipal election that he intended to vote only for women for every office listed on his ballot and challenged me to do the same. “No,” I told him. “Anyone who’d do something so manifestly stupid should forfeit the right to vote.” “I’m still going to do it,” he said, grinning like a mischievous kid. And I have no doubt that he followed through on his threat to devalue his ballot in such a reckless way. And yet here is the great and curious thing about Cam. While a stunt like that might well irritate me when perpetrated by another; with him I always found it funny and endearing. This disparity of our philosophical temperaments didn’t discourage the blossoming of our friendship at all but instead loaned it the added lustre of amusement, wonder and intrigue. I’m sure we both had cause on multiple occasions to ponder some utterance the other had made – in person or in print – and reflect to ourselves, “So, apparently, it really is possible for a sane and honourable person to think that way.” Already retired by the time I met him, and never inclined to boast about his own accomplishments, I only gradually came to understand that over the years Cam had undertaken just about every job there was in the world of journalism and public relations. As he had done most of that work in Ontario cities other than London, I had a very sketchy grasp of his overall career trajectory and am grateful to his daughter, Mary Pat, for filling in a lot of the details in the wonderful obituary she had printed in The London Free Press and The Ottawa Citizen on October 10th and in our conversation at the reception after the funeral .(A true pressman’s daughter, she signed off that obituary with a “–30–”.) The second oldest of five brothers, G. Campbell McDonald was born into a family of Irish descent in the predominantly English-speaking town of Granby in Eastern Quebec, where Cam's father was a foreman at the Empire Tobacco Company. He landed his first piece in a newspaper at the age of 12 when the weekly Granby Leader Mail published his poem, A Schoolboy’s Dreams. Cam's high school education concluded with three years as a boarder at Loyola High School in Montreal, a Jesuit-run prep school affiliated with Loyola College. Though a childhood hockey injury necessitated the wearing of glasses, 19 year-old Cam was so determined to get into the action of World War II that he deviously memorized the sequencing of letters on the commonly used eye chart so as to more readily pass his enlistment exam with the Royal Canadian Artillery where he was signed on as a gunner in the 24th/75th Field Battery of Granby and Cowansville. His sub-standard vision was occasionally a problem, as he reported in a January, 1944 letter home, explaining to his parents why there would be a bit of a delay in sending them an updated photo to put up on the piano: ""I'm afraid I can't get it done now because my civvy glasses are broken and I split my upper lip in the blackout and the fog last week. My own fault. I walked smartly (??) into the rear-vision mirror on the outside of a stalled tactical vehicle during a night exercise the Colonel sprung on us. I haven't a clue when I'll be able to get up to London to have my specs fixed. I'll be sporting respirator glasses till I do." 20/20 eyesight or not, Cam served in the Canadian Army right through to the end of the war in 1945, rising to the rank of lieutenant as a regimental artillery officer. He recounted his very last moment of engagement in a note responding to a reference I'd made in a column to the seething hatred which the Poles maintained for the Nazis: "The Polish Armoured Division was part of the Canadian Army in battle in North-west Europe. When the cease-fire order came down in Germany at midnight, May 4, 1945, I passed the order to my guns and they fell silent. The Polish artillery regiment was on our right - they kept on firing until every last shell they had exploded on German soil!."  Sue McDonald with baby Mary Pat outside their veteran’s bungalow in Northeast London Sue McDonald with baby Mary Pat outside their veteran’s bungalow in Northeast London Back on Civvy Street a few months later, Cam wasted no time in marrying a Montreal girl, Sue Danford. We have a couple of scrapbooks of crayon drawings that Sue worked on as a young child and mixed in among her renderings of goldfish in a bowl, birds fighting over a worm, a young girl sledding, the cow jumping over the moon, a portrait of Jean Harlow, etc., are dozens and dozens of drawings of comic strip characters like Mutt & Jeff, Felix the Cat, and Maggie & Jiggs. As Cam was constantly referencing philosophical insights he had gleaned from such strips as Pogo and Li'i Abner (and once worked up a feature for SCENE on Al Capp's invention of Sadie Hawkins Day) one can imagine at least one shared enthusiasm that might've drawn these two together. In 1947 the young couple came to London while Cam studied journalism at UWO, living in humble, pre-fab housing supplied at a bargain price by the Department of Veterans Affairs,. In 2003 Cam wrote a short essay for London Street Names: An Illustrated Guide, edited by Michael Baker and Hilary Bates Neary, in which he described that domiciliary adventure and his introduction to London: The Bellwood Park subdivision originated in northeast London as a postwar nursery where baby carriages outnumbered cars twenty-to-one . . . Applications for the 186 neat little bungalows and storey-and-a-half houses were ranked in priority by a Department of Veterans Affairs points system based on length of overseas service and number of children. My family of three (later four) became happy homesteaders at a Grosvenor Street bungalow for $35 a month . . . Our two bedroom house came equipped with a gas stove and icebox, a wood/coal furnace in the cellar, a back stoop with a clothesline pole, seeded lawns in front and back, and a gravel driveway. Our next door neighbours were ex-Navy and ex-Air Force; I was ex-Army. Besides our shared military backgrounds, many of us were fellow students at the University of Western Ontario, having moved to London to take advantage of the government’s program for student veterans. All of his life Cam was rightfully proud of his half-decade in the Army. Also pinned to one of the boards at his funeral were the half dozen medals he’d earned and a yellowed instructional monograph that he’d written and typed up for the men in his unit on the defusing of incendiary devices. I couldn’t help muttering “Good for you,” at the end of his funeral mass when we all stood up to sing the recessional hymn he had personally chosen; the currently reviled (too pugnacious, don't ya know?) Onward Christian Soldiers. Cam maintained an encyclopedic grasp of Canadian military history as is manifest in that essay’s concluding paragraph: Today, by virtue of its street names, Bellwood Park remains an ever-green war memorial. Ortona Road, Falaise Road and Apeldoorn Crescent memorialize the battles won by London’s Royal Canadian Regiment at Ortona in Italy, by London’s First Hussars Armoured Regiment at Normandy’s Falaise Gap in France, and by both regiments at Apeldoorn in the liberation of Holland. Watling Street, Wallbrook Crescent, and Mincing Lane pay lasting tribute to some of London England’s most heavily bombed streets. Bellwood Park and its main thoroughfare, Bellwood Crescent, are named after James S. Bell, the city treasurer who played a leading role in the project’s financing. After graduating in 1949, Cam’s first paid journalism gig was as the editor of a newly overhauled weekly newspaper, The Wallaceburg Standard. I asked him to write a column for SCENE about that first journalistic posting and, perhaps because he didn’t have much respect for the ethics of the paper’s owners, he didn’t deign to name the paper or the town: I was a new boy in town, freshly arrived from university to put out a weekly newspaper. The man who stepped from the street into my aisle-sized office was big. When I looked up, he seemed to almost fill the door frame. He held a small sheet of paper in his hand. “You the editor?” he asked. I said I was. “You charge for birth notices?” “No, we’re happy to run them for free. Boy or girl?” “Boy. Came last week. It’s written here.” I took the note. The family name was Sands. “Congratulations, Mr. Sands. We’ll have it in the paper next Thursday.” We shook hands. He filled the door again on his way out. I leaned over my desk and handed the information to the local woman whom I’d inherited as bookkeeper-cum-secretary from the paper’s former publisher. She glanced at the name and address and frowned. “We don’t print these,” she said. “Oh! Why not?” “They’re Indians . . . from Walpole Island.” Thus it was, in the summer of ’49, the birth notice appeared and my secretary, by invitation, disappeared.  Cam during his stint at CFRA Radio in Ottawa Cam during his stint at CFRA Radio in Ottawa OVER THE COURSE OF what Mary Pat called Cam’s “many careers in the communications arts”, he worked as a “journalist, broadcaster, TV anchor, innovator and mentor.” His longest radio gig was at CFRA Radio in Ottawa where he eventually became news director. By the 1960s he was moving more into the fields of public relations and became communications coordinator for Alumni Affairs at UWO and in his retirement years also served as an adjunct professor at Western’s Graduate School of Journalism. Mary Pat noted that Cam was especially proud to have been a founding director of the Native News Network of Canada and the founding chairman of the Ontario Advertising Review Board. Cam also worked extensively for the Ontario government during the premiership of Bill Davis. During those years at Queens Park he helped to develop Ontario Place which opened in 1971 and he also got to meet the Pope in the course of planning out the logistics of John Paul II’s first visit to Toronto in 1984 when he presided at an enormous outdoor mass at Downsview Park. I was one of an estimated 300,000 people crammed into that rain-churned field of mud that day (it was sort of like Woodstock for the religiously zealous) and ten years later, Cam rooted through his trunk of souvenirs to give me an official gold and white papal-visit ball-cap of my very own. Cam and I were both devotees of old school manual typewriters and held out against certain digital innovations in the publishing world for as long as we possibly could. Shortly before he and Sue moved to Toronto in the late ‘90s so they could be closer to their kids and their families, Cam started dropping off his stockpiled fleet of crapped-out Underwoods and Royals to my house for "safe keeping". I still have the hand-written note in his beautiful, red, felt-tip script that Cam taped to one of these machines that he left on our front porch like a mangled, abandoned infant: “Sue’s typewriter needs a new ribbon, otherwise it’s (Clunk! Wham!) functional. Enjoy!” The fanciful conceit we were concocting here was that when civilization collapsed and the whole electric grid went down for good, I’d be able to haul a couple of these 30-pound relics up out of the basement and, with a bit of a tuneup, we two newshounds would be back in business and providing fresh copy to a post-apocalyptic world. In secret, I think we both understood this was hooey; that we'd never be using these typewriters again and sooner or later I'd face that melancholy fact and quietly dispose of the whole lot. While we’d both been using word processors and printers for a few years, we didn’t actually get hooked up to the internet until 2002. And it so happened that we were both experimenting with some of our first emails to each other on the day when Sue suddenly and quietly died in the living room of their Toronto apartment; a dreadful occurrence I learned about electronically shortly after it happened. I may even have been the first person he told. My guts evaporated at the news and also at the shocking immediacy with which it was conveyed. Just an hour before we'd been merrily corresponding about the scuttlebutt in the latest issue of Frank and now his entire world had been flipped upside down. I remembered another day when I'd seen this notably happy man suddenly wracked by grief. In January of 1996 Cam came over to the house, eager to pick up some extra copies of the latest SCENE, still warm from the printers, in which we’d published his tribute to his younger brother. Kenneth McDonald (1925-45) was one of the first boys to take training with the Air Cadet League of Canada so that he could be sworn into the R.C.A.F. as soon as he turned 18 in 1942. One year later, he met up with Cam in England who took him out on a sight-seeing tour of the Big Smoke: "When he arrived in England full of ginger, our joyous reunion in London combined a pub crawl, a Palladium revue and a spectacular air raid as we dashed to take shelter in the Underground. The next day I showed him the sights of Piccadilly Circus and Soho and we had our picture taken together to send home." Kenneth received his King’s commission as a Pilot Officer at the age of 19 and was killed in action one year after that; six months before the end of the war and five and a half months before his 21st birthday. The Kid Who Was Born to Fly, we called the story and I’d ransacked my library to find a suitable cover image; coming up with a dramatic vintage sketch of five airmen and ground crew standing beneath a sky that is half-darkened by a wave of Lancaster bombers flying overhead. The picture was an unlikely shape to build a cover around – more of a banner than a poster shape – but Kirtley found an ingenious way to reconfigure the usual image-to-text relation. I don’t recall if Cam knew his story was getting the cover. He certainly didn’t know about the picture. “Oh, it’s perfect,” he said, taking up a copy and then suddenly folding it as he sat down sobbing in my study chair. I stood awkwardly by his side for a couple of minutes, wanting to say something to comfort him but knowing I didn't have access to any words with that kind of power. And then his sobs subsided of their own volition, he flattened out the magazine on his lap, looked me in the face and repeated himself in a reassuringly steady voice. "It's just perfect. Thank you so much."  Cam circa 2006, around the last time we visited Cam circa 2006, around the last time we visited LATER THAT YEAR, Kirtley and I bailed out of SCENE when the publisher fell under the sway of trendy consultants who persuaded him to take the magazine in a different, more youth-oriented direction. Cam pitched in (with a lot of other good souls) and tried to help me get another local weekly up and running. We had some great brainstorming meetings in one of the upstairs rooms at Fellini Koolini’s where (for some reason that nobody still remembers) Cam and Kirtley had to avoid each other’s eyes or they’d succumb to fits of the giggles. (I wonder if it had something to do with the preposterous spectacle of watching me attempt to chair a meeting?) I rounded up enough fresh articles from a handful of writers (including some who left SCENE at the same time we did) to print up a preview copy of something we called The London Sunday Journal. We shopped it around to various potential investors but none were prepared to risk it. By about 1998, Cam and Sue were getting ready to move to Toronto and we had them both over for a farewell supper. That was the only real visit we ever had with Sue. She was getting a little ditzy by then and had come up with her very own method - equally ingenious and mad - for keeping track of stuff inside her cavernous purse by attaching everything to sections of string so that it looked like a game of cat's cradle when you peered into its depths. But all in all, the pair of them propped each other up beautifully and the rapport between them was as cozy and familiar as your favourite pair of slippers. At one point in the evening, however, Cam once again was assailed by sudden grief. I don't recall how we got onto the subject. But I do rmember some confusion about a Captain Kenneth McDonald who died in an air accident. I assumed Cam was talking about his brother and was appalled to discover that Cam and Sue's only son who was named after Cam's late brother was a Canadian Navy helicopter pilot who died in 1974, leaving a wife and infant son behind..Indeed, Cam and Sue's later residence in London was largely about being near and helping out their widowed daughter-in-law and grandson; and when the young folk skedaddled off to Toronto, Cam and Sue did likewise. Cam made a special trip down to London in 2003 when Kirtley's No Comment exhibition was on at Museum London in conjunction with the big Greg Curnoe retrospective, Life & Stuff. And we went down to visit with Cam in Toronto twice. The first time, I think, was early in 2004, as I recall that I was still feeling pretty raw after the recent death of my father. Cam took us out to dinner and the prearranged cab rides, the reservations at a nearby restaurant and the schedule that had to be strictly adhered to gave the whole outing the feel of a military operation. Cam was reflecting back on the war a lot just then and was regularly posting columns of his military reminiscences in The Sherbrooke Record, the big daily in that corner of Quebec where his journalistic career had been launched 71 years before with A Schoolboy's Dreams. Over dessert, Cam was getting a little judgmental about the inferiority of men, as soldiers, who waited around to be drafted as opposed to those who stepped forward and enlisted straight away. When I mentioned that my Dad had been drafted, he hastily dialed it back. "But he was married then, wasn't he?" Cam asked. "It was entirely different if you were married." As a matter of fact, I don't think Jack would've taken much umbrage at Cam's original charge. He was no military keener, no happy warrior like Cam, and he knew that about himself. I heard him marvel sometimes about how strong and fit he felt after a few months' basic training; how salutary it would be if such a regimen could be maintained in civilian life. But otherwise Jack did not have an eventful war. He never even shipped overseas, didn't develop any skills or capacities as a result of being in the army, and would have been perfectly content if his name had never been pulled out of that particular hat . . . or helmet. On our last visit in 2006, Cam wasn't so ambitious a host and we ate a dinner his housekeeper had prepared at his apartment. The focus was better this time with fewer distractions and no schedule to adhere to. It was always a pleasure to visit with him but in subtle ways the undertone this time was more sombre and constrained. He had recently taken a fall and inside the apartment, one could see that he wasn't making as much use of his space; wasn't so inclined to go fetch something from another room to show you but confined himself more to certain stations such as his chair at the kitchen table and the desk in his bedroom where his big computer monitor was set up. Things were clearly starting to wind down and his stamina was ebbing away. Cam always liked to give me books; usually beautiful Folio Society editions which he carefully selected for me and presented in person or mailed. Scanning my shelves I see a number of the cherished titles that came from him: Tales of the Unexpected by Roald Dahl. Lyn Macdonald's anthology of British war poets, Anthem for Doomed Youth. Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. Agatha Christie's Miss Marple Stories. Deirdre Le Faye's edition of Jane Austen's Letters. The Once and Future King by T.H. White. Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. Frank Barlow's Life of Thomas Becket. On this night he pointed to a few books set out on a hallway stand and asked if there was anything there that I wanted and I chose John Betjeman's Selected Poems. He was visibly tired by the end of our visit and didn't see us to the door this time but said his goodbyes from a chair in the hall as we let ourselves out of his apartment. I looked at him one last time as I pulled the door to and had a strong sense we'd never see him again and we didn't. But more than a year later Cam would send one final and particularly inspired gift winging its way towards me via Canada Post. I hadn't seen any notices that in 2007 the Folio Society would be bringing out a deluxe edition of Poems by my main man , G.K. Chesterton, and then, 'thud', there it was, like an impossible tome that had dropped out of Heaven and landed between my doors. The Folio Society is renowned throughout the English-speaking world for the superb craftsmanship that goes into every aspect of the books they publish. Their rigorous quality control supposedly prevents the release of any sloppy or shoddy products. But when you flip open the cover and front end-paper of this particular volume, you confront a solid page of text that begins mid-sentence – in fact, mid-hyphenated word (an orphaned 'bing' removed from its preceding 'throb-') – on page XVII of the preface. The first sixteen pages haven't simply been excised; they inexplicably turn up at the very back end of the book. Cam noticed the blunder as well and wrote an inscription on a yellow post-it note which he slapped onto the front end-paper: "HG: Skullduggery in the bindery! Love, Cam." "He cried at his children’s graduations and weddings," Mary Pat noted in her obituary notice of Cam. And when she went up to the ambo to say a few welcoming words before the funeral mass got underway, she was struggling to maintain her own composure and chided herself in an exasperated tone: "I seem to have inherited my dad’s penchant for tears. But I’m not really sad. This isn't a sad occasion." Indeed it was not. It was great to meet and talk with the 50 or so people who turned out for the mass and to know that a good number of them had remained in constant communion with him until the very end. We, on the other hand, had completely lost touch with Cam over the last twelve years which he spent in a veterans’ care home and, mindful of his advanced age, would think of him from time to time and assume he must have slipped away by now and that nobody in his family had thought to send up a flare to let his old London connections know. So for me, seeing his obituary in the paper was another, "Good for you" moment. I mean, how many of us get ninety-eight years in which to make our mark upon the world? And regardless of how much time we get, how many of us are able to play out our allotted span with such high spirits and such generosity of heart; such openness to everything - the joyful and the heartbreaking - that life throws our way? Unable to accompany me to the funeral, Kirtley sent me along with a couple of swatches from the work she's been stitching together for the last few months; replicating three pages from one of Cam's childhood journals in which he jotted down sixteen resolutions for amending his behaviour. The list reads as follows. The spelling and punctuation are eight year-old Cam's. RESOLUTIONS 1. Do not smoke. 2. Do not go to bed later than 8:30 every night. 3. Always obey your mother and father and suprieours. 4. Do not grumble when you are asked to do something. 5. Do not fight if you don't have to. 6. Be tidy and neat. 7. Do a good turn to somebody every day. 8. Always be helpful when you can be. 9. Do not swear. 10. Do not tell lies. 11. Do not go with bad company. 12. Save every cent you get. 13. Do not be a tattle-tail. 14. Do not boast. 15. When you start to do a thing always finish it. 16. Be friends with your enemies. Yours truly, G.C.McD. I love the qualifiers for Resolutions 5 and 8 which acknowledge that there are indeed times when fighting is necessary and when assistance can't be proffered. Emblematic of the existential struggles and ethical shifts that are underway within each heart throughout our lives (and which flare up with particular intensity during adolescence), a few years later a more cynical Cam felt a kind of contempt for his prissy younger self and drew a big black 'X' across each one of those pages. But that censorious iteration of Cam did not get the last word either. He didn't tear up his resolutions or burn them. Indeed, we have no evidence that Cam ever deliberately discarded a single piece of paper in his life; certainly nothing that had any sort of writing on it. And if it didn't have any writing on it yet . . . well, Cam would soon fix that. No, his inky condemnation didn't even obscure a single word of the original document and he kept those 'X'ed out pages until he was an old man. And then at the age of 86, when Kirtley asked him for some representative sample of his handwriting from which she could develop what they both understood would be a sort of "portrait," those were the pages he chose to give her. Mary Pat gasped and put a hand to her heart when I showed her the swatch on which Kirtley had recreated her young father's 16th resolution and signature in thread, with the end of the right tail of the third 'X' just poking down from above. "Oh no, I'm going to cry again," she said. "Yeh, it's been a really good day for that," I assured her. And then a huddle of mourners just behind us exploded in laughter at the denouement of another great story about Cam. "And for that too." Photo Credit: Bellwood Park subdivision - London Street Names, An Illustrated Guide. Edited by Michael Baker and Hilary Bates Neary (2003). James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Toronto, Canada.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed