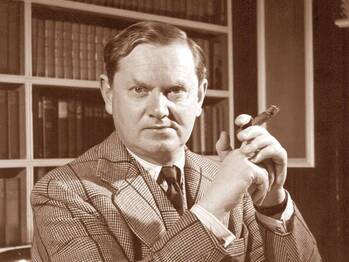

EVELYN WAUGH (1903–66) EVELYN WAUGH (1903–66) LONDON, ONTARIO - To mark this 75th anniversary of the first publication of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, I have re-read my favourite 20th century Catholic novel for the third time and – just tonight – finished re-watching the magnificent, eleven-episode Granada TV adaptation of the book for at least the fourth time. When that mini-series originally aired on the PBS network in 1981, we had neither cable nor a colour TV but we did have a brand new baby – our very first – who very graciously consented to sleep through the 60 to 90 minutes of air time when we invaded my in-laws’ living room for eleven weeks in a row. (Hoping there might be something Emily found innately soothing about the Masterpiece Theatre theme music or Alistair Cooke’s spoken introductions, we tried repeating this stunt the following year when PBS aired their adaptation of Paul Scott’s The Jewel in the Crown. But Em wasn’t so co-operative in 1982 and we had to wait about ten more years to catch up with that series on video.) Brideshead Revisited was my introduction to both Evelyn Waugh (1903–66) and his most popular book by far; a romantic, wonderfully funny and powerfully moving novel whose theme – as stated by Waugh himself – was “the operation of divine grace on a group of diverse but closely connected characters”. The story spans the years from 1922 to 1944 and is narrated by Charles Ryder, a bright but rather zipped-up only child of an emotionally distant widowed father whose surreal non-conversations with his son, shot through with a toying kind of sadism, are regularly recurring highlights of both the series and the book. When we first meet Charles, he is just beginning academic studies at Oxford University. He has a capacity for draughtsmanship but no clear idea what he intends to do with his talent or his life until his third term when he falls in with the divertingly glamorous Sebastian Flyte who acts as the magnetic centre of a set of budding aesthetes. A charming flouter of every convention going (and, it soon becomes obvious, an Olympian dipsomaniac-in-training) Sebastian is the younger and wilder son of the disgraced Lord Marchmain who has abandoned his too pious and too controlling wife and their four children to live in Venice with his mistress. If his friendship with Sebastian emboldens Charles to court fascination from vital sources infinitely more responsive than a university prospectus, it is his repeated and extended visits to the Flyte family’s country estate of Brideshead that focuses Charles’ talents as an architectural painter. “It was an aesthetic education to live within those walls,” Charles narrates, “to wander from room to room, from the Soanesque library to the Chinese drawing room, adazzle with gilt pagodas and nodding mandarins, painted paper and Chippendale fretwork, from the Pompeian parlour to the great tapestry-hung hall which stood unchanged, as it had been designed two hundred and fifty years before, to sit, hour by hour, in the shade looking out on the terrace . . . and, in the centre, dominating the whole splendid space rose the fountain; such a fountain as one might expect to find in a piazza of southern Italy; such a fountain as was, indeed, found there a century ago by one of Sebastian’s ancestors; found, purchased, imported, and re-erected in an alien but welcoming climate . . . “This was my conversion to the baroque. Here under that high and insolent dome, under those coffered ceilings; here as I passed through those arches and broken pediments to the pillared shade beyond and sat, hour by hour, before the fountain, probing its shadows, tracing its lingering echoes, rejoicing in all its clustered feats of daring and invention, I felt a whole new system of nerves alive within me, as though the water that spurted and bubbled among its stones was indeed a life-giving spring.” Equally attractive to Charles as this stunningly grand house are the fascinating people who have grown up inside it. They too constitute an education for the comparatively isolated Charles in the dynamics of family life and the way in which characteristics and experiences common to this closely-knit group take on different forms in the development and expression of each individual. Of the four children born to Lord and Lady Marchmain – abandoned to the exclusive care of their mother as children and steeped in every precept and nuance of the catechism throughout their growing up – two take on the faith so completely that they hope (in vain, as it turns out) that they have callings to the religious life. These are Bridey, the eldest son, and Cordelia, the baby daughter. The coldly logical Bridey is both blazingly brilliant and woefully obtuse; a perfectly hopeless reader of people who causes so much inadvertent offense that he rarely gets a chance to impart the knowledge he possesses. The much more generous-hearted Cordelia (though occasionally mischievous) has a knack for taking anybody’s measure in seconds flat but routinely goes her own way with such quiet self-containment that her gifts are commonly overlooked. There’s a sort of parlour game that lovers of Brideshead Revisited like to play with one another, believing as we do that your answer to the question, "Who's your favourite Flyte?" reveals so much about you. Well, Cordelia is mine.  Anthony Andrews and Jeremy Irons in Brideshead Revisited (1981) Anthony Andrews and Jeremy Irons in Brideshead Revisited (1981) It’s the two Flytes in the middle, Sebastian and his equally worldly and even more headstrong sister, Julia, who struggle most valiantly, and mess up their lives most completely, in trying to elude the clutches of – almost literally in their case – Mother Church. And of course, it is those two rebel Flytes, who successively elicit what turns out to be the doomed love of the agnostic Charles Ryder. No small part of the fun of the book or the series is to watch, in one situation and conversation after another, as the uncomprehending Charles smacks up against and tries to make sense of the religious reflexes of all the members of this beguiling family. I particularly enjoy this exchange between Charles and Bridey as they clear out Sebastian’s rooms at Oxford – finding bottles of booze stashed everywhere – after Sebastian has been sent down in disgrace after one too many benders. This is the first big demotion in what will turn out to be Sebastian’s steady descent to the exiled half-life of a remittance man who is given a regular allowance to disappoint his family somewhere beyond the range of their sight, like Tunis. Irked that Bridey’s demeanour is “as grave and impersonal as ever” as they carry out this melancholy task of erasure, Charles bristles when the older brother just comes out and says, “My mother thinks Sebastian is a confirmed drunkard. Is he?” “He’s in danger of becoming one.” “I believe God prefers drunkards to a lot of respectable people.” “For God’s sake,” I said, for I was near to tears that morning, “why bring God into everything?” “I’m sorry. I forgot. But you know, that’s an extremely funny question.” “Is it?” “To me. Not to you.” “No, not to me. It seems to me that without your religion, Sebastian would have the chance to be a happy and healthy man.” “It’s arguable,” said Brideshead [who then fastens on an umbrella stand he covets]. “Do you think he will need this elephant’s foot again?” Amazingly, with Brideshead Revisited it really doesn’t matter if you take in the book or the TV series first. Both deliver the Full Meal Deal. Not even three hundred pages long, there is very little indeed that didn’t get carried over, intact and meticulously observed, from the book to the 650 minute running time of the series. With whole sections set in Oxford and at Brideshead, in Venice and South America, in New York City and London and on board a trans-Atlantic liner, it is common for people who take up the book after seeing the series to be amazed at its un-thickness. "But the story feels so epic . . ." Many establishing shots and sequences of transition come with whole paragraphs of Waugh’s ravishing prose narrated in the voice of (then) new star Jeremy Irons who played Charles Ryder. Laurence Olivier and Claire Bloom played Lord and Lady Marchmain. John Gielgud played Charles’ father. The always dependable Mona Washbourne played the superannuated Nanny Hawkins who resides in the attic of Brideshead where she is regularly visited by the now-adult Flyte children when they need a little grounding. Simon Jones played Bridey, Diana Quick was Julia, Anthony Andrews was Sebastian and Phoebe Nicholls played Cordelia and went on to marry the director of the whole enterprise, 28-year old Charles Sturridge, a couple years after the production wrapped. (So I guess we know who Sturridge's favourite Flyte is.) Originally conceived as a six hour series with an adapted script by John Mortimer (of Rumpole of the Bailey fame) the series took almost three years to make because the production had to be halted twice; first for a four-month technicians' strike and then for even longer when Jeremy Irons had to fulfill his first big movie contract on the set of The French Lieutenant’s Woman before he could resume his work with Brideshead. Shooting could hardly proceed without him as he appears in virtually every scene.. Those interruptions so easily could have derailed the show or at least messed up its coherence but cast and crew were uniquely dedicated to the project. Everybody was reading and re-reading the novel to keep up to speed and finding wonderful bits that hadn't been included in the first screenplay. Then, one by one, various players started approaching the director and producer, Derek Granger, with requests to find a way to include this bit or that scene with the net result that the total running time more than doubled during downtime. John Mortimer was fine with including more scenes so long as the dialogue was lifted straight from the book. And he remained the only credited writer even though, in the final analysis, he only worked up about half of the scenes that made it into the final series. I don’t know of a more faithful or complete adaptation from book to screen anywhere. Brideshead Revisited was a watershed book for Waugh; written when he knew he was at the peak of his powers and racking up sales like nothing else in his canon. Interestingly enough, he thought it would bomb in America where his sales were never that hot anyway because of the Anglophilia of so many of its themes. In fact its American sales greatly outstripped total British sales when the Book-of-the-Month club chose it as a main selection. As things turned out, it was in Britain where a case could be made that its release was ill-timed. Lest we forget, in 1945 Britain had just sent Winston Churchill packing - "Thanks for helping us through the war and all that but we fancy a change" - and elected its first Labour government. So a spanking new novel whose plot points Kingsley Amis would witheringly summarize as “How I Lived in a Very Big House and Found God”, was not primed to win a warm reception at home. A number of influential British critics who had loved Waugh’s earlier (and, it must be admitted, more one-dimensional) satires like Decline and Fall, Vile Bodies, Black Mischief, A Handful of Dust, Scoop and Put Out More Flags, regarded Brideshead as an aberration, an establishment butt-kissing sellout and a betrayal of his talent. And then, there is always that portion of the reading public – more plentiful in Britain than America at that time – who will roll their eyes impatiently at anyone who is so gauche as to render a sympathetic account of religious faith. Waugh was accused of snobbery and elitism and - an entirely new charge for him - of perpetrating purple prose. He'd always been an exquisite writer but such perfectly-tuned prose in the service of satire only increases its bite; whereas it seems to arouse suspicion when employed in a more full-bodied tale. For all of his celebrated crustiness, Waugh was a sensitive man and these new and disparaging charges stung. Waugh tweaked the book for a new edition in 1960, recognizing, he said, that the austerities of the war years had perhaps engendered a reactionary overindulgence. “It was a bleak period of present privation and threatening disaster – the period of soya beans and Basic English – and in consequence the book is infused with a kind of gluttony, for food and wine, for the splendours of the recent past, and for rhetorical and ornamental language, which now with a full stomach I find distasteful. I have modified the grosser passages but have not obliterated them because they are an essential part of the book.” I admit there are a couple of passages I could either do without or which I would submit to a very vigorous haircut. Charles as narrator commits one grotesquely clunky declaration just after he and Julia, having cheated on their disappointing and pretty well discarded spouses, finally have their way with one another. I notice the filmmakers of Brideshead Revisited discreetly deep-sixed this bit as well. And good for them. (Yeah, I know, writers never set a foot wrong when describing sexual congress, do they?) And then there’s Julia’s famous speech at the fountain when an undiplomatic observation from Bridey about her and Charles “living in sin,” detonates her own sense of religious guilt. Blindsided by the awful realization of just how much damage her willfulness has caused to others and to her own soul, a sudden injured outburst would have said so much more than this sobbing Gettysburg Address of remorse which sheds a little more credibility with each additional phrase of elegantly couched self-incrimination. But I find such momentary glitches eminently forgivable in the far larger context of this magically exhilarating novel that gets so much so perfectly right. For instance, I don’t know any other novel which so beautifully evokes the bonds of excitement and love that can operate between young male friends when they awaken new capacities within each other. And I’ve never seen a more lifelike portrayal of the simple habituation, the no-nonsense efficiency, with which Catholics carry out their devotions and prayers. As the great Newman scholar, Fr. Ian Ker, writes in a chapter on Waugh in The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, “The idea that religion is a natural part of life, not something to be brought out solemnly on Sundays, is a recurring theme . . . The job to which all the Flyte family are called, is the practice of Catholicism.” Ker's main point in that essay is that it was the practice of good craftsmanship which most dependably elicited Waugh's respect, whether he encountered it in a carpenter, an artist, a penitent or a priest. And the hallmarks of that practice were a submission to the laws that legitimately pertain in any situation and a striving, whenever possible, to embody truth and beauty in our actions and our work. I believe this same simple credo is expressed in Waugh's thrilling account of Charles striving to meet an unrealistic deadline for his very first commission when Bridey appoints him to work up some interiors of the family’s London home, Marchmain House, just before it falls to the wreckers: “I had the perspective set out in pencil, and the detail carefully placed. I held back from painting, like a diver on the water’s edge; once in I found myself buoyed and exhilarated. I was normally a slow and deliberate painter; that afternoon and all next day, and the day after, I worked fast. I could do nothing wrong. At the end of each passage I paused, tense, afraid to start the next, fearing, like a gambler, that luck must turn and the pile be lost. Bit by bit, minute by minute, the thing came into being. There were no difficulties; the intricate multiplicity of light and colour became a whole; the right colour was where I wanted it on the palette; each brush stroke as soon as it was complete, seemed to have been there always.” And that same note of respect for work carried out well is struck in this book's climax when an unassuming local priest refutes the charge of a sceptical Charles Ryder and the attending physician he's trying to marshal to his side, that in spite of what the Flyte children might want, it is monstrous to ask the priest to give the last rites to the disbelieving and barely conscious Lord Marchmain who has returned to Brideshead to die: "Now doctor," said the priest, "how would I be a shock to anyone?" He turned his bland, innocent, matter-of-fact face first on the doctor, then upon the rest of us. "Do you know what I want to do? It is something so small, no show about it. I don't wear special clothes, you know. I just go as I am. He knows the look of me now. There's nothing alarming. I just want to ask him if he is sorry for his sins. I want him to make some little sign of assent; I want him, anyway, not to refuse me; then I want to give him God's pardon. Then, though that's not essential, I want to anoint him. It is nothing, a touch of the fingers, just some oil from this little box, look it is nothing to hurt him." When the last physical act of Lord Marchmain’s ebbing life is to slowly, silently make the sign of the cross over his brow and breast, Charles knows that his dream of marrying Julia and living with her at Brideshead has irrevocably dissolved. And yet his long and tangled romance with this family and this place has brought him to a larger consummation, though it will be a couple years before he realizes it. The Catholic scholar and translator of Dante, Anthony Esolen, beautifully describes the transformation that has taken place in his book-long meditation on home and belonging, Nostalgia: “Charles Ryder, the successful dilettante, the antiquarian, the Bohemian poseur, is finally woven into a true culture. Brideshead is his home, not because he grew up there (he did not), but because it has placed him, as if he were a stone, in an ancient edifice of meaning. He is in communion with the Crusaders who fought at Acre, now in ruins, and Jerusalem, also in ruins. He is in communion with the friend of his youth, the alcoholic Sebastian, now an exile, a pilgrim, and a man with a home, half in and half out of a community of monks in North Africa, where one morning, as his sister Cordelia foretells, ‘after one of his drinking bouts, he’ll be picked up at the gate dying, and show by a mere flicker of the eyelid that he is conscious when they give him the last sacraments. It’s not such a bad way of getting through one’s life.’” Waugh converted to Catholicism in his late twenties after the humiliating collapse of his first marriage to an unfaithful woman who also happened to have the first name of Evelyn. He credited that decision for saving his sanity and his life and went on to write a number of worthwhile books on Catholic subjects, including superb biographies of 16th century martyr Edmund Campion and his own contemporary and good friend, Monsignor Ronald Knox, whose posthumously collected sermons (some of the finest in the English language) Waugh also had a hand in editing. Waugh also wrote a novelization of the life of St. Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. And a more recently published exchange of his letters with John Cardinal Heenan on the liturgical changes ushered in by Vatican II - A Bitter Trial – shows how upsetting those alterations were to this thorough-going traditionalist. Waugh’s death on Easter Sunday of 1966 at the age of sixty-three was actually seen by some as a blessing as they couldn’t imagine what discomfort it would've caused if he’d still been around when Catholics were required to turn to their fellow parishioners shortly before the distribution of the Eucharist to say, “Peace be with you.” Waugh’s only other fully-fledged (which is to say, non-satirical) novels are those which comprise his late war trilogy - Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen and Unconditional Surrender - collectively entitled, Sword of Honour. I’ve never been able to get past the first volume, finding the characterizations thin and the humour strained but some folks I respect, including Fr. Ker, actually regard them as the supreme expression of the more mature and religiously informed Waugh. So I guess I still have those to look forward to though it's hard to imagine that they'll ever win a place in my esteem to compare with Brideshead Revisited.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed