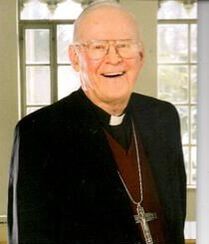

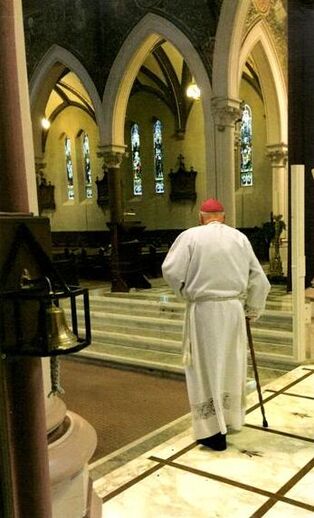

BISHOP SHERLOCK BISHOP SHERLOCK LONDON, ONTARIO – With the death on August 12th of Bishop John Michael Sherlock at the age of 93, I expect that I am not the only member of the sprawling Diocese of London, whose sense of bereavement has been mixed with bursts of jubilation at a race that was so very well run. I shall indeed miss his steadying presence in the day to day life of our local Church but it would seem ungrateful and even myopic to only express regret at a death which came at such a good age; or to wish for the prolongation of a life which the Bishop himself was willing and prepared to let go. Always a courageously forthright man who met challenges and adventures head on, I never knew Bishop Sherlock to hold back from any prospect. If anything, he was perhaps at times a little too impetuous in speaking his mind. But whenever he overshot the mark (and I’m not saying this happened routinely or even often) he soon realized it and just as courageously admitted his fault and apologized. Instinctively convivial, the Bishop sought to see the best in people and for the most part, that generosity of spirit was reciprocated. I knew of people who disagreed with him but none who bore him a grudge. I often recall a brilliant autumn afternoon when we fell into a brief conversation outside the old central library and he must have exchanged greetings with a half dozen different interlopers who happened by in just those few minutes as we unlocked our bikes and piled our newly leased books into our carriers. A lot of civic leaders make a point of avoiding situations where their elbows might get rubbed in such a random way but the Bishop never seemed to find such encounters a strain. The years of Sherlock’s episcopacy (1978–2002) almost perfectly coincided with the years of St. John Paul II’s papacy (1978–2005). And in his capacity as president of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, he organized the 1984 Papal visit to Canada and accompanied JPII all across the country. It was a time he looked back on with special fondness for the rest of his life.  Bishop Sherlock with St. Pope John Paul II. Bishop Sherlock with St. Pope John Paul II. In 1994, I was the editor of SCENE magazine and Bishop Sherlock did not hesitate to take me up when I asked if he would sit for a feature interview in our humble little rag that more often than not, featured rock stars of dubious moral and intellectual distinction on the front cover. I think he saw it as an opportunity to engage in a little community outreach; to bring the message of Christ’s salvific love to a whole new kind of congregation. After establishing his birth in Saskatchewan and his childhood in Brantford, I asked him how old he was when he first knew he was called to the priesthood and couldn’t help saying “Yikes” when he gave the monosyllabic answer of “Six”. “It’s unusual but it’s not unique,” he went on to explain. “When I was six I made my first communion and my aunt gave me a book about saints. The story that I read was about Isaac Jogues who was one of the Canadian Jesuit martyrs. In this story, Isaac’s mother was reading to him from The Jesuit Relations, and as his mother read to him about New France in the 1600s, Isaac knew that he would become a priest and go to the new world. And when I read that, it was just like a light went on in my head – I’m going to do that too.” And from his personal background, we ventured into deeper, theological waters. I asked him how literal our interpretation of the Bible should be. “My answer is the same as St. Augustine’s. ‘I would not believe the Bible if the Church did not tell me to.’ The Bible needs an outside testimony to establish its credibility – and that testimony has always been the Christian community. The Bible did not fall out of the heavens from the hand of God. It was produced in the community, by the community and under the inspiration of the same Holy Spirit that was given to the community at Pentecost. “We have to accept that the Bible is inspired by God and that it teaches truth. But the Bible is made up of all kinds of literature. There is poetry. There is history told not so much to tell about the past as to illustrate a moral point. The creation narratives in the Book of Genesis are a profound commentary on spiritual reality; on the fact that we are creatures, on the fact that God is the source of all being, and on the fact that evil is now a part of human experience, that it is something that God did not create; something for which we have a responsibility, something which God in His goodness and mercy enables us to surmount through His grace. There is fiction. The parables of Jesus were stories he made up to illustrate a point. This was the rabbinical tradition. Was there a Good Samaritan? Probably not. But the point of the story is no less valid; that people who don’t even share faith with us are often the people who demonstrate in practice what it truly means to love your neighbor.” And for our interview’s conclusion, I dropped the big one; asking him to explain the presence of evil in a world created by a loving God. I read out to him this journal entry by the Catholic poet and essayist, Alice Meynell (1847–1922), following the death of her five month-old child: “We have something to forgive God for. We have something to forgive the Creator who makes husband and wife grow one only to smite them in two again. Who prodigally overdoes and exaggerates the love in a mother’s heart and then forces her to watch a child’s long agony. If we saw all we should have nothing to forgive. But He makes us see little and He must wish us to forgive Him. We forgive Thee, our Maker, for thy infinite inventiveness in planning the anguish of human life.” “Is that blasphemy?” I asked him. “It’s not blasphemy,” he answered. “It’s great pain. It reminds me a lot of some of the Psalms where the people cry out bitterly. Or the Book of Job. I had a brother, a priest, who died very suddenly. A niece of mine is a Carmelite nun in a convent in Norwich, England. The prioress at that convent writes under the pen name of Ruth Burrows and she wrote to me a most startling sentiment when she heard about my brother’s death. She wrote, “Be consoled because God weeps with you.” Theologically – it’s not accurate. But it expresses in human terms a truth that we cannot adequately grasp. When you look at Jesus weeping at the tomb of His friend, Lazarus, when you see Him weeping over the city of Jerusalem – then you know that this is a divine person who does share our pain and grief. Rather than pardoning God because He arranged for my child to die in agony, I would rather see God as weeping with me because of what the evil in the world has brought about even on this helpless child. I don’t know how disease fits into the pattern of sin, but there’s not much doubt in my mind that prior to the coming of sin among us, there was no disease. And yet God does not intervene in most of our pain because to do so would be to turn all His creatures into a robot; because the causes of all these things lie somewhere in the exercise of human liberty.” Fr. Michael Prieur, who taught moral theology for almost 50 years at St. Peter’s Seminary and regularly looked in on the ailing Bishop throughout these last six months of his final physical decline, told me that his faithful colleague was ready to go: “He was a man of deep prayer and love for his brother bishops across the country and his own priests. Every day he prayed for many of them – by name – for at least 20 minutes. His elephantine memory remained until the end. On Pentecost Sunday this year during Mass on request, he recited the complete Sequence Veni Creator Spiritus in Latin. It underlined his love of the Trinity, especially the Holy Spirit. He also had a deep devotion to the oil of St. Joseph from the Oratory in Montreal, often offering it to people asking for his prayers. Right up to his 93rd birthday this January, he loved to celebrate the weekly Monday Eucharist at the Cathedral, and especially hearing confessions for an hour beforehand. He was always a pastor at heart. “A month before his death, sitting in his chair he pronounced, ‘This dying thing is difficult’. He was ready every day. On a recent visit, he said he had a question for me. On offering to discuss it immediately, he declared, ‘Not now; I will call you at the end.’ He died about five days later, without calling me. He remained a bishop right to the end. I am sure God was able to answer his question. May he rest in peace.” Bishop Sherlock’s funeral Mass at a packed St. Peter’s Cathedral Basilica on Friday, August 15th was a splendidly cathartic ceremony with clergy in attendance from all across the country who helped to form an honour guard that flanked his coffin’s progress from the front steps of the Cathedral all the way down to Dufferin Street where his hearse awaited. The Bishop himself had chosen all the readings and hymns; none more exquisitely apt than the stirring processional hymn, O God, Beyond All Praising, set to that sublime tune which composer Gustav Holst named Thaxted. But more than our interview or his funeral, the encounter I’ve been recalling most frequently these last few weeks, is that Easter Vigil ceremony in 1984 when Bishop Sherlock baptized me and anointed me with holy oils and brought me into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church. Ever since that night he has been for me a man set apart by God who beckons me into the light. And that is a role that does not end with his death. A shorter version of this essay appeared in the August 25, 2019 edition of The Catholic Register.

1 Comment

Ninian Mellamphy

2/9/2019 10:48:04 am

What a memorable synopsis of the life of Bishop Sherlock!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed