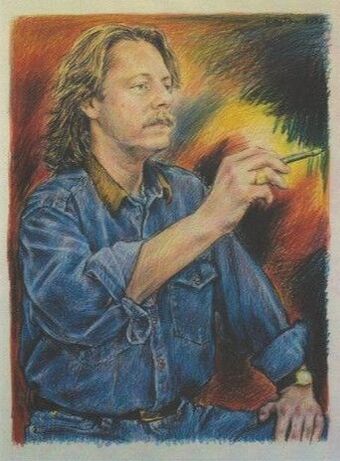

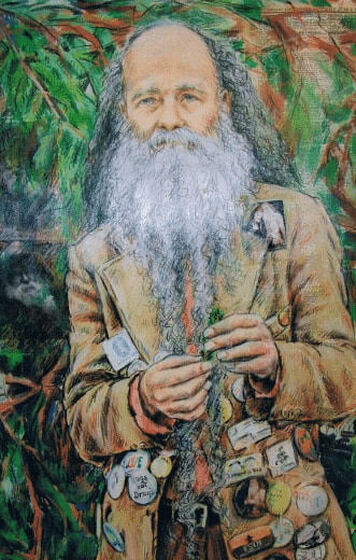

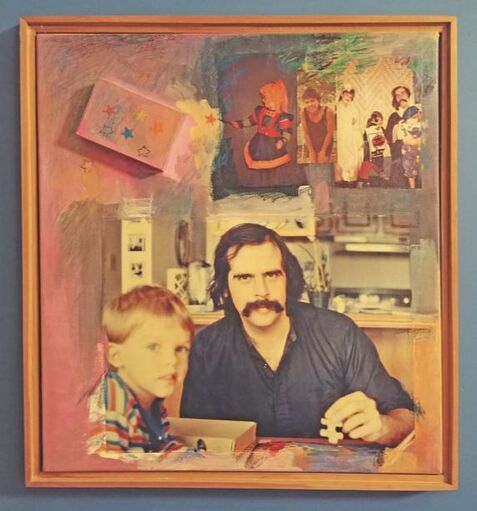

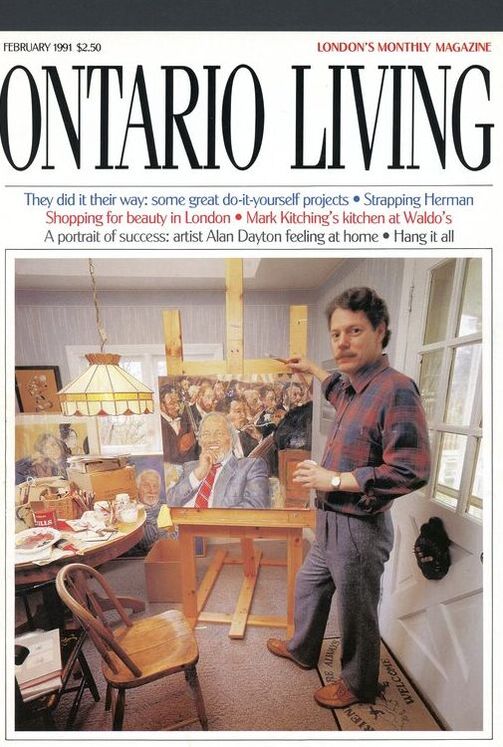

Alan Dayton: Self Portrait Alan Dayton: Self Portrait LONDON, ONTARIO – Colleagues and patrons were completely blindsided when London artist, Alan Dayton (1949–2013) died ten years ago this May at the age of 64. It took several months for family and friends to pull together a memorial and retrospective exhibition for him at Eric Stach and Catherine Morrisey’s riverside studio as not even those closest to him knew anything was wrong until very shortly before the end. Dayton may have justified his secrecy as a strategy to spare others anxiety and dread. But shocked as his friends were to learn that he had even been ill, they also shook their heads in rueful recognition that so discreet an exit perfectly accorded with the man they knew and so suddenly missed. The shy and reticent Dayton never did call attention to himself. Indeed, his forte as London’s foremost portraitist was to lavish his attention on others. I first met Alan in the fall of 1987 when – quite out of the blue - he called to invite me up to his York Street apartment across from the train station to see some of his work and discuss the prospect of having my portrait painted. I was perhaps equal parts flattered and appalled that anyone might be interested in rendering my likeness and was pretty sure that I wouldn’t be able to afford a portrait even if he went ahead and created one. Alan said there was no obligation for me to buy a painting; he wanted to do it anyway as part of a show of portraits of writers’ that he was putting together. Believing our first meeting would only be a brief ‘sounding out’ session and not a formal sitting, I made zero effort to look any more presentable than usual and took along our then-three year-old son, Hugh, who liked to tag along on excursions into town because he knew I’d find a way to visit at least one used bookshop on the way home and – if the gods were smiling - would also take him into the Zellers toy department to pick up another ninety-nine cent Dinky Toy; one of which always seemed to be clutched in his little right fist. Buzzed up to Alan’s apartment, we immediately surveyed an impressive array of recent portraits - these ones mostly of visual artists - that were hung all along the hallway and into the big front room which Alan used as his studio. When I reciprocated with a portrait of Alan four years later in a profile for Ontario Living magazine, his wife, Sue, told me of the territorial campaigns that were waged in every space they lived; how Alan would initially set up his easel in some back corner and then incrementally take over all the largest, best lit rooms. I was immediately struck by his portraits’ remarkable verisimilitude – for I instantly recognized most of the subjects – and his brilliant use of colour. I was impressed that this guy I’d never heard of before seemed to have arrived on the London scene full-blown, fully formed, and was painting the town one citizen at a time with uncanny skill and vigour. As a father of four himself, Alan knew a thing or two about how to keep a three year-old occupied and set me and Hugh up at a table with a picture puzzle of a farm scene as he gathered information about my background and my so-called career and, somehow quite un-invasively, shot off a couple dozen photographs. After about an hour of what felt like nothing more arduous than easy-going - if a little one-sided – conversation, Alan announced that my sitting was complete and he had what he needed for developing my portrait. I did eventually buy it – and the price wasn’t all that punishing – and in 1990 the portrait took its place with thirty-two others (including such heavy hitters as Robertson Davies and Margaret Atwood) in a traveling exhibition called Figures of Speech which was shown in galleries across Ontario and the National Library in Ottawa. It was never Alan Dayton’s way to push himself forward or suck up to the usual mavens and gatekeepers of high culture. He always proceeded quietly in a self-directed way, seeking to secure the physical and the mental space that would allow him to devise his own way forward. His artistic progress was not charted by working his way from some backwater to the centre. His entire trajectory was quite opposite to that. Born in New York City in 1949, his family moved to San Diego when Alan’s s stockbroker father retired. While he definitely acquired some preliminary skills during his first couple decades in the States, Alan wasn’t able to start painting in a serious way until he eliminated the besetting distraction of possibly getting drafted into the army. This he achieved by coming up to Canada with Sue in 1969; first setting up his easel in Montreal and then Toronto but not releasing any of his work for public exhibition until moving to London on a recklessly intuitive whim in 1974. After finishing high school and meeting Sue, Alan had enrolled in English and art at UCLA; not because he particularly wanted to study anything but just to evade the draft board’s clutches. He bailed out of university in the middle of his second year, unable to keep up the charade any longer. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life,” he told me in our 1990 interview. “I felt all these pressures. I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. I didn’t want to be in university just so I could keep out of the army. I came up to Canada as an alternative to going into the army or prison or pretending I was psychotic. “I was going to come up on my own and Sue would come up later – either when and if she got her parents’ consent or when she turned 18. I got as far as Chicago, landed at the airport there and was feeling real uneasy, had this incredible headache. I didn’t feel right about it, changed my ticket and flew back to California. We decided we’d come up together. It was time to act, to roll the dice. This was our lives and it was time to make our own decisions.” Though Sue still wasn’t quite 18 and her parents would not give their consent, they stopped short of constraining their daughter and the couple fled the country of their birth. “We just loved Montreal,” Alan said. “And we were such babes in the woods. The whole FLQ thing was starting up around then and we had no idea. There was also this big barn of a building not far from our place and every now and then at night we’d hear this incredible roaring sound in there. One night I stopped somebody to ask what it was and he just looked at me like I was from Mars and said ‘the Montreal Canadiens’. And I said, ‘What’s that?’ ‘Hockey,’ he said and walked away.” The Daytons – married by this time – were looking forward to their first Canadian winter. “We couldn’t wait for the snow,” Alan told me with a foolish grin. “The first week in November, it started, and we thought ‘that’s good’ but then it kept coming and just didn’t stop. We were totally unprepared for that.” They were starting to feel a little hemmed in, Sue was pregnant and, said Alan, “We figured if we were going to have a baby . . . we’d have to be able to speak to people, you know? So we thought maybe English would be a good idea and moved to Toronto that February.” “We might’ve left Montreal sooner than we did,” Sue interjected, “but we were waiting for all these canvases to dry. That was sort of what we brought with us to Ontario – Alan’s first oil paintings.”  Alan's portrait of Roy McDonald Alan's portrait of Roy McDonald “They were horrible,” Alan remembered. “I was doing copies of medieval religious paintings, some work that was reminiscent of Dali, portraits of Sue and myself. It was real exciting when I was doing it but when I looked at them afterwards, I would just be amazed. Sometimes it took an hour, sometimes a few days, but the magic just wouldn’t be there anymore. There was so much to learn. I’d say my apprenticeship took twenty years and for the first ten years, I hated most of my work and for the second ten years, I at least liked most of it, I could usually see what I was getting at. So I guess that’s progress. “It took me a long time before I was ready to exhibit, to really commit to being an artist. I didn’t know any other artists for years and years. Not being Canadian, I didn’t have any school friends or professional contacts. Except for a few life drawing classes, I was working in real isolation. I had some sort of personal notion of what I wanted my work to be and as long as I fell short of that, I wasn’t going to push it out there yet.” The Daytons landed in the Beaches area of Toronto where their first two children were born. Then when Hogtown started to become too pricey, they cast around for somewhere more financially forgiving to live. What ultimately drew the budding artist to London in 1974 was seeing the Jack Chambers Retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario: “I didn’t know of him or his work at all – walked into the gallery and was really quite moved by it. He had two sons like we did. And he looked like such an approachable guy in his photographs – none of that Salvador Dali exhibitionist routine. I liked all the blue sky in the paintings, the feeling he expressed for his community. And that was London.” In recounting his impulsive foray to check out the lay of the land down Souwesto way, Dayton voiced one of the sweetest tributes to London that I’ve ever heard: “I drove over one day to have a look and there were all those trees and the sky – I recognized it all from his paintings. It felt like the opening of some Fellini film where you get the bird’s eye view of a community and you know that everything you’ll need for a great story is being laid out before you. The frame is small enough that you can take it all in but it’s big enough that you know there’s going to be some surprises – there’s enough scope to allow diversity and movement. London is a great resource for an artist. A greater artist could do even more with less but the human pageant is all here.” Alan lived and worked in London for the next two decades and in that time he built up a solid reputation as London’s foremost portraitist, chronicling everybody from politicians and cultural leaders to street people. Never content to prop his subjects up against bookcases, curtains or Romanesque columns, Alan distinguished himself not only for the uncanny likeness of his portraits but for the attention to personal detail that showed up in his backgrounds. “It’s still a very mysterious process to me. I love doing portraits. The best portraits are always a collaboration between the subject and myself. I talk with them and learn about them while I take a few photos and a lot of the details I learn will show up in the background. I often work on the background first and that will create a suggestive environment. When it comes time to place the subject within that environment . . . that can be quite daunting . . . trying to find that single image that will best express your subject’s personality.” A lot of artists shy away from portraiture. This is partly because it can be a bit of a ghetto that doesn’t garner much in the way of critical attention but also because portraits are so notoriously difficult to do well. And if the subject of a portrait isn’t pleased then who else is likely to buy it? When I wrote up a short talk to give at Alan’s memorial, I asked London artist Kevin Bice to comment on Alan’s work and the challenges of portraiture in particular. “People want a likeness, right?” Bice said. “A single photographic image rarely cuts it. Who’s ever been happy with their school photographs? With portraiture, all it takes is a subtle miscalculation in proportion or nuance and the whole thing goes south. As an artist I really envy anyone like Alan who could keep that sort of focus and find it endlessly absorbing. With my own work I tend to flip around like a grade nine boy at a dance but Alan really had a fascination with portraiture that never seemed to end.” Alan primarily switched to portraiture in 1984 and attracted lots of individual commissions. On the side, he liked to do his series and in addition to his traveling show of writers’ portraits, he produced similar series of visual artists, theatre people, and perhaps most tellingly, street people. The very first portrait he ever exhibited was his 1977 painting of Jessie Robbins, who was a touchstone of Old South London, famous for riding her bicycle in all weathers and collecting twigs in her basket carrier. That painting sold quickly at the 37th Western Ontario Exhibition but a more important confirmation of the work’s worth for Dayton was the fact that Jessie haunted the gallery for the duration of the show, proudly standing next to her portrait each day and chatting with patrons. It was a hallmark achievement that made both the artist and his subject feel validated. Following the collapse of his marriage to Sue in the mid ‘90s - and the official extension of amnesty to Vietnam-era draft dodgers - Alan felt the need for a change of scene and returned to the States for about a decade with his second wife, Phillipa, exhibiting his work extensively in Florida galleries and museums. His return to London in 2005 was commemorated in a show at the Art Exchange that year entitled, Coming Home. His return also coincided with the first burblings of a group show celebrating the Thames River where I was able to reconnect with him. I wrote up essays on all of the 19 artists involved in that show and Alan contributed portraits of people – including six of the The River Project’s artists – who lived by the river.  Alan's portrait of Herman Goodden (1987) Alan's portrait of Herman Goodden (1987) “Since I’d just come back I was certainly interested in reconnecting with artists in London," Alan recalled. "I told Kevin [Bice: the leader of the Project] at first that I didn’t know what I’d be able to do but I would be glad to come to the parties. And finally I thought I’d better do something. Being primarily a figurative painter and assuming that most of the other artists would be doing more landscape-based work, I said that what I thought I could contribute was portraits of people who live along the river, showing them in the river environment.” When I was interviewing Alan about his portraits, Phillipa, who took the photographs which he worked into his canvases, told me how she was born in South America in what used to be British Guyana and then moved to Dutch Guyana, emigrating to Canada when she was about 15. Dayton couldn’t resist commenting in mock condescension, “She’s had such a limited experience of rivers, really. Just the Orinoco and the Amazon. Nothing so grand as the Thames.” And when I asked what their favourite stretch of the river was, Alan’s answer managed to touch on both the origin and what would turn out to be the terminus of his long and fruitful affinity with the unlikely city where he chose to leave his most lasting mark. “We generally walk from here up through Gibbon’s Park. My own personal thing is the pair of trees planted for Jack Chambers and Olga Chambers in the north part of Gibbon’s Park. I usually walk up to there as a kind of gesture of respect. And I enjoy that walk. But sometimes we walk south down the river to Eric and Catherine’s studio. So that would be our stretch of the river.”

2 Comments

Randy and Beth Stewart

1/12/2023 10:53:49 am

Thank you for the tribute to Alan.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

2/12/2023 10:21:26 am

I enjoyed your last two posts enormously Herman, you are so much better and accessible when you leave out the politics. No need to be an Ontario Londoner to enjoy "The Battle of the Bands". As a young London England Londoner I remember the development of the music scene from the "Trad Jazz" clubs of the late fifties populated mainly by Jiving university students and mid-twenty year-olds to the discos of the mid-sixties where teenagers could dance to pop records. The 100 Club at 100 Oxford Street opened in 1942 to Swing Time and Big Band was where GI's brought the Jitterbug to England. The cry there was "ignore the Doodlebugs, come to the 100 and Jitterbug". I found it when it had morphed into, by the late fifties, a trad jazz club with a resident Humphrey Lyttleton and I was still there when at the death of "trad" the club was again reborn as England's premier blues club with a resident Alexis Korner's Blues Band where a host of young blues musicians like Georgie Fame cut their eye teeth before going on to form their own bands. My own locals, West Hampstead's, which I have mentioned before, Klooks Kleeck and Witches Cauldron Cellar at Belsize Park like Richmond's Crawdaddy where the Stones began, Ricky Tick at Windsor where everyone appeared at one time or another, have all gone. Recently though, looking something up, I found that they (and no doubt many more) all have internet sites with their potted history and pathways to other connected sites where one can add facts and memories.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed