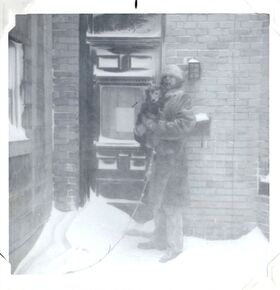

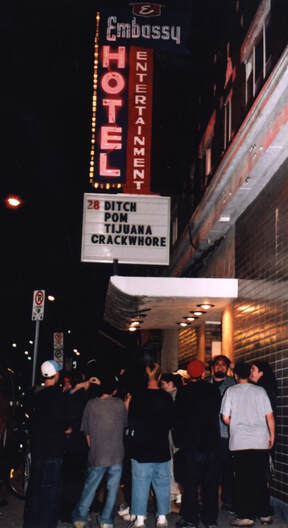

Herman and Myrtle at 728 Dundas St. in the blizzard of ‘77 Herman and Myrtle at 728 Dundas St. in the blizzard of ‘77 LONDON, ONTARIO – There was a glowingly optimistic feature in last Saturday’s Free Press about the promise of revitalization and an economic turnaround for East London that might be spurred by the overhaul of the gargantuan old Kellogg’s cereal factory as a mixed-use space that will eventually house a relocated Children’s Museum and Canadian Medical Hall of Fame, a distillery, a brewery, some kind of simulated golf course, a hotel, a market and food hall, and more executive offices than you can shake a stick at. Well, I don’t want to rain on anybody’s parade here but I’ll believe it when I see it. It could, of course, be that I’m old and out of touch and worn down to a cynical nub by the regularly repeated experiences of my lifetime when one over-hyped new elixir after another has failed to effect the promised transformation of London’s east end. I don’t have much faith in the power of one-off projects to turn around whole civic sectors. And while we yearn and hope for such magic bullets to work their magic, I’m struck by a kind of collective ingratitude for what East London already is: a more generally affordable, working class section of town with some wonderfully intact old neighbourhoods and its own unique sense of community. This city has looked down on East London for decades for its seediness and its crime but – except for several blocks of Dundas Street from Adelaide east to Rectory – it’s an unwarranted slander. At least that stretch used to be the danger zone. I know because I moved to the festering heart of it at the age of 22, drawn by the bar-none cheapest rent in town. The only definite plus I foresaw in moving out on my own was that I’d be able to blare my records at paint-peeling volume any time of the day or night and nobody would have any say in the matter but me. And so I’d spun the third Audience album on my trusty turntable one night around 12:30 and just as Howard Werth was bellowing his way through Jackdaw, an empty bottle of Old Vienna came smashing through my front window; a little request from my neighbour across the way who perhaps would’ve preferred something by The Carpenters. It wasn’t the first or the last time I regretted ever setting out on that period of exile and impoverishment known as ‘living in bachelor digs’. Forsooth, I’m sometimes amazed that young men ever move out on their own at all. An irresistible lure or a very strong repellent is required to dislodge any ageing child from the ease and comfort of his parents’ home and I didn’t really have either. I’d moved into my parents’ basement at the age of fifteen and had all the space, privacy and freedom that I required and no compelling reason to strike out on my own. About once every 24 hours my parents liked to know where I was and there was a sort of standing request that I refrain from finishing up the last of the milk during late night raids on the fridge. Wildly irritating as I found these impositions at the time, even then I knew that as violators of human rights my parents would never make it onto the Amnesty International blacklist. The sad truth of the matter was that as parents go, mine were just about ideal. They knew that all I really wanted to do was write and seemed content to let me work at various low-paying jobs in a part time way to earn spending money and otherwise devote the main part of my energy and time to writing. I was one of the last in my circle of friends to move out on my own and while I still wasn’t mad about the idea of scratching together money for rent, buying my own groceries and cooking my own meals, I could see in a half-embarrassed sort of way that the time had probably come. I’d agreed in principle to split the $135 a month rent on a back alley slum tucked in behind Lucky’s Open Kitchen at 728 Dundas St. East (rear). But then moving day came and went and I was still comfortably ensconced in my psychedelic dungeon in the family home on Wortley Road. I didn’t know how to drive, wasn’t about to rent a moving van and certainly wasn’t about to go anywhere without the real staples of my existence – my mammoth book and record collections. I guess I didn’t believe I was going. I certainly hadn’t mentioned a word of it to my parents. I was sitting down to supper with my parents one evening in late September when some friends of my brother showed up with a borrowed van. They went downstairs and started tearing my room apart while I returned to the table and officially – permanently – excused myself. “What’s so important that you can’t finish your supper?” asked Mom. “Uh . . . I guess I’m moving out.” “Now? But I made those Rice Krispie squares for dessert.” Dear God, I was going to start crying if she didn’t stop it. In the soles of my feet, I could feel the harsh wrenching sound as bolted crates were pulled away from the wall one floor below. “Can’t we talk about it at least?” she asked. I couldn’t even think about it and looking at Dad, found some refuge in his objectivity. Mother was the million tiny particulars, the atmosphere and soul of our home. I couldn’t look her in the face and still believe I was going. Dad didn’t say a word; wasn’t going to push it one way or the other but in his eyes I saw a kind of confirmation; that if I wanted it, then the time had come. About an hour later I was carrying the last random scraps of my worldly belongings out to the van (a piggy-bank shaped like Colonel Sanders and a lacrosse stick; why do I have such things?) when Mom tackled me in the hall, all teary-eyed at the departure of her youngest. “It’s so sudden,” she said. “I really wasn’t expecting this until you got married.” “No,” I told her, smiling as bravely as I could. “When I get married, we’re moving back in here.” That same night at two a.m., rearranging familiar furnishings in a strange room that I didn’t much like, I was numb with my sense of displacement and loss but had so far held off tears. I congratulated myself for pulling off the impossible. I was finally acting my age and was amazed to have eluded that cataclysmic sorrow which I had feared would overwhelm me. Desiring a cigarette to puff on while pondering just what a mature fellow I’d become, I reached into my shoulder bag for a fresh book of matches and came upon a wax-paper bundle of Rice Krispie squares that I hadn’t put there and proceeded to weep like an idiot. Much as I wanted to, I didn’t turn tail and run home. A tip for any parent whose kids keep moving back: encourage your child to cultivate enormous collections of just about anything. In the contest between inertia and homesickness, an overwhelming quantity of junk can act as a very decisive anchor. I stayed in that place for four years, outlasting four other cohabitants and racking up a bill for rent in arrears to the tune of more than a thousand dollars. The rent was not steep. In my final year my landlord apologetically bumped it up to $150 a month. But I mention this disgraceful business about the arrears because it illustrates how un-seriously I took this whole enterprise. I used my fridge for cooling bottles of beer and coke and that was all the kitchen I really needed. I made coffee on a hotplate in my bedroom upstairs and could easily go months without turning on the stove, mostly subsisting on bags of chips and leftover food at the restaurant where I washed dishes. I lugged laundry home to my parents once every couple of weeks and acquired impromptu and mismatched furniture from neighbouring curbs and dump sites. When a home represents so very little to a young man – smelly clothes and bed, cast off furnishings, appalling food – is it any wonder that he might resent paying for all this deprivation? That he might fall behind in his rent? That nothing would be more welcome than the eviction notice that would send him back to live with Mom and Dad? But my landlord did not evict me. In fact my debt was hovering around the $500 mark that second Christmas when he dropped me off a bottle of sparkling Ontario wine, saying I was one of his ‘preferred tenants’. Who was living in his other apartments? Satan’s Choice? I was living in a badly dilapidated 19th century townhouse and once I’d cleared out a defunct, cast iron furnace from the basement, I had three full floors of rotting decrepitude to play with. The story was that there used to be two or three more townhouse units attached to the north but these had burned down; probably, I imagined, in some Al Capone-style act of arsonic vengeance between clashing drug lords. I once answered a knock at the front door from a rather dazed-looking older woman, checking in to see whether an old acquaintance of hers still lived there or did I know where he’d moved to. I’m afraid I wasn’t much help to her and regarded her with such alarm and skepticism that I probably managed to undermine her own sense of her mental acuity. The place had been empty, virtually unrentable, for a couple years before I moved in. My front door opened onto the so-called compost heap behind Lucky’s Open Kitchen and just beyond it loomed the western wall of the Embassy Hotel, blotting out all sunlight until the early afternoon. The alleyway leading out to Dundas Street was only three feet wide and among my more immediate neighbours were a strip club, a body rub joint, a bar, a tattoo parlour and half a dozen flop houses. So we weren’t talking about a prestigious rental property.  The last days of the Embassy Hotel The last days of the Embassy Hotel You can imagine what an education it was for this naive and aspiring writer to move out of his parents’ ivy-covered pile in old South London to take up habitation in this darkest corner of the city that common decency forgot. Prostitutes serviced their not very fussy clients in the corner between my front door and Lucky’s back wall. Staggering oafs full of too much beer routinely peed and occasionally threw up on that barren patch of ground that was my excuse for a front lawn. In silent disbelief I once watched a young woman take a dump there in broad daylight. One of the first nights in our new digs, my co-tenant and I were yanked away from our game of Scrabble by the sound of shattering glass nearby and a ringing burglar alarm. We ran out the front door and that bell sound, now winding down, seemed to be coming from the alley that led out to Dundas Street. Amidst shards of glass on the alley floor, an alarm clock metallically vibrated away in its death throes. So, not a smash and grab after all. Some poor old soak, sleeping off a bender in one of the Embassy’s sparsely appointed rooms, had been rudely yanked to by the blaring ring and pitched the nasty thing through a window. My co-tenant wanted to investigate further and I was propping up his bum as he tried to crawl his way up between the alley walls when a policeman at the Dundas Street end of the alley swept a brilliant flashlight beam across our blinking faces. “But . . . but Officer . . . We live here. We were just checking out the noise.” It didn’t look good but thankfully, he believed us. In fact, I think he felt kind of sorry for us. We regaled him for about five minutes with breathless tales of all the unsavoury things we’d seen since moving in and he looked more amused than shocked to learn what was going on in this neck of the woods. When we finally finished our tirade, it was his turn to speak. I paraphrase but I swear on a stack of Embassy Hotel Gideon Bibles that the gist of what he said was this: “You seem to want the police to do something about all of this but I might just point out to you that we recently moved our headquarters to the corner down there. And that was no accident. We know what’s going on here and frankly – as long as it’s contained to this neighbourhood – we don’t intend to bother very much about the small stuff. But if it’s a quiet, peaceful life you want . . . well, I’ll tell you what I’d do: I’d move.” In 1997 I related that story to then-Chief Julian Fantino and he said to me, “I don’t believe that any neighbourhood should be relegated as a war zone, a drugs-tolerant zone, a prostitution-tolerant zone. That’s despicable. Not everybody can live in the Windermere Manors and the people who live down here are no less entitled to safety and quality of life than anyone else.” Well, Fantino talked a pretty good game but during his reign as chief my old stomping ground didn't exactly settle down. I remember one report from that period of a drug-addled chap chasing his pusher down Dundas while swinging a machete overhead. During the first December in my new home, I was thunderstruck by a window display at Simpson’s Department Store downtown, promoting the annual Salvation Army Christmas drive. They’d wanted to present a grim image of the kind of blighted urban squalor which the Sally Ann works to alleviate and there was a huge dramatic photograph of a drunk, empty bottle at his feet, head in his hands, sitting on my front stoop. When I pointed at the picture and blurted in amazement – “Hey, that’s my house!” nearby shoppers pulled their coats a little tighter round their shoulders and scuttled away. The earnings from my part-time dish-washing job obviously weren’t sufficient for me to carry the rent on my own. I should have been soliciting new roommates whenever an old one left but instead I would mark each co-tenant’s passing with another bout of home improvements. I was big on the ‘open’ concept and eventually demolished every interior wall on the first and second floor except those surrounding the bathroom. (There are some functions I’d just as soon not share with others.) I had a brief mania for Mr. Ed-style Dutch doors, put in a trap door and ladder leading from the living room to the cellar (I justified that ‘improvement’ as a fire exit) and seriously considered the installation of a fireman’s pole at bedside that would get me to the downstairs fridge in two seconds flat. Luckily, I never found a suitable pole or length of pipe. Though I couldn’t really afford to live alone, I had so completely made over my surroundings to reflect my own twisted and immature tastes that nobody else could stand living there. Including my wife. When I finally did move out, it was eight and a half months after getting married. (She had her own small apartment about floor blocks away, west of Adelaide Street and next door to the restaurant where we both worked.) There was that small matter of the arrears to clear up before I could move and as two budding artists who didn’t want to over-invade each other’s physical and psychic space, we were leery of getting too married right away. Also it took us a while to shed our Aquarian pretensions. There was something so pedestrian, so irredeemably Ozzie and Harriet about getting married that we had to incrementally sneak up on the concept of all that relentless overlapping. Plus it was a cheap source of amusement to see how puzzling our domestic arrangement was to our parents and even some of our more conventional friends. Personal friends moved in for a couple of years after I left in 1978. And once they moved out the stained glass transom over the front door and two panes over the windows were pillaged, everything was boarded over with plywood and the house stood empty and increasingly derelict for almost three decades until the 2009 fire that destroyed the Embassy Hotel next door. There was about a ten-year period starting in the ‘90s when the Embassy actually started booking some decent bands rather than the dreadful C&W two-piece combos who proliferated during my residency in the hood. (If I had a nickel for every rancid cover version I ever heard of Charlie Rich’s Behind Closed Doors, I’d be able to buy at least a case of beer.) Two Embassy gigs whose memory I cherish to this day were the magnificent Mutton Birds out of New Zealand circa 1994 and several years later, the Embassy’s very last hurrah as a concert venue with Guided by Voices out of the States. Every year when our kids were small and we attended the Western Fair, we’d park nearby and I’d take them around to see their pappy’s first home. It gave them the wiggling creeps. It was just the kind of place they’d instinctively avoid at Hallowe’en. But taken all in all, I look back on my tenancy there with real fondness. Yes, the neighbourhood could get oppressive in the summer but the winters covered everything with a deep and penetrating stillness and were very copacetic; even paradisal in a Shangrila-on-a-budget sort of way. We had a whole series of great, city-paralyzing blizzards in the mid-70s when all I had to do was read and write all day, play my music and hang out with the woman I’d just married. I got my first dog in that house and raised her from a puppy which inculcated a lot of skills that came in handy when we started having babies a few years later. It was a tough neighbourhood, all right, but nothing I couldn’t handle and rise above in my fearless twenties and it outfitted me beautifully for the rest of my life. In comparison, every home we’ve lived in since then - both of them - has seemed absolutely perfect in every way.

3 Comments

Vanessa

24/2/2020 12:56:58 pm

A fantastic piece.

Reply

Peter Jarvis

24/2/2020 04:13:13 pm

I loved the story of your somewhat squalid bachelor digs and your mother’s kindness and thoughtfulness.I hope that your current wife makes you rice Chrissy squares occasionally.

Reply

Max Lucchesi

25/2/2020 12:23:04 am

Hopefully your artist wife bought along a pot or two of paint. A coat of paint was something you never mentioned when listing your home improvements. Can I assume your conversion to Catholicism was your final leap into adulthood? I think most of us have been there, at one time or another. Me, I've lost two libraries during my travels and moves including my collections of Doctor Strange, Silver Surfer and the black and white folio Conan the Barbarian set. Take heart Herman, it's taken almost three hundred years to turn the East End of London into gentrified Docklands.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed