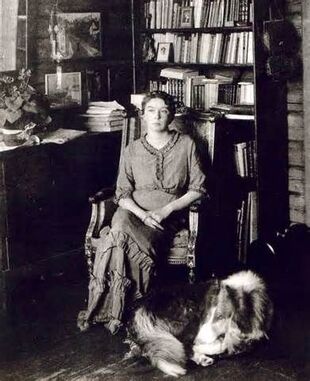

Sigrid Undset (1882 – 1949) Sigrid Undset (1882 – 1949) LONDON, ONTARIO – Prompted by a glowing commendation this spring by David Warren on his Essays in Idleness website, I finally read Sigrid Undset’s (1882–1949) triple-decker saga of life in Medieval Norway, Kristin Lavransdatter. Originally published in three installments – The Bridal Wreath (1923), The Mistress of Husaby (1925), and The Cross (1927) – Kristin Lavransdatter was collectively awarded The Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. In that essay, Mr. Warren was insistent that an English reader who wanted the richest possible Lavransdatter experience, must seek out the original translation by Charles Archer and J.S. Scott and avoid the streamlined, mildly sexed-up revamping by one Tiina Nunnally which is being peddled by Penguin Books today. Luckily the original translation sold in sufficient numbers back in the day that a trawl through a good used book shop or the interwebs will still turn it up readily enough. Liv Ullman clearly based her three-hour 1995 film of the first book on the Nunnally translation. Despite a few casting infelicities mostly having to do with too-old actors and some narrative threads that were feebly elided or dispensed with altogether, I’m not sorry to have seen it as a sort of visual supplement to the book. Particularly in the matter of 14th century Norwegian domestic architecture and clothing, the film filled in some gaps in my visualization. Yes, the old translation does come with twenty pages of endnotes that illuminate such details but not so tangibly as seeing them on the screen. I’ve had a 1929 single-volume edition of Kristen Lavransdatter on my shelf for yonks. Intimidated by its 1066 page-heft and the battery of Scandinavian names and historic arcana that assails the reader in the opening pages, I resisted diving in. But mindful of the esteem in which the book was held by such considerable worthies as Willa Cather and Dorothy Day, I kept it in my ‘one-of-these-days’ pile and now am ever so grateful that I did. Undset met both Cather and Day during the five years she spent in the USA on the lam from the Nazis during their occupation of Norway. Cather’s best biographer, Hermione Lee, writes that, “The New World greatly impressed [Undset], especially the mid-West. Like Cather, she was a strong woman with a deep feeling for people’s spiritual relation to their land and their past; they got on well. (Indeed, it was Cather’s only warm relationship with a woman writer of her own stature and generation.) Cather . . . admired Undset’s large, heroic warmth and calm, her truthfulness, her ability to surmount her losses, and her combination of the artist, the peasant and the scholar.” That introductory barrage of data and impressions that must be construed before a reader can proceed with Kristin Lavransdatter, is not unlike those first ten panicky minutes at Stratford when you settle into your seat to watch a production of some less-renowned Shakespeare play and think, “Oh man, my mind’s gone to pot. These people might as well be babbling at me in Portuguese free verse. I’ll never get my bearings.” But, “perseverance furthers” as the I Ching says, and eventually the story begins to coalesce and take hold, shaking the wool from your wits as it bears you along and reminding you that utterly exotic transports like this are one of the great services that books uniquely provide. I remember the ordinarily circumspect female clerk at Attic Books who sold me my Lavransdatter so many moons ago with a look of profoundest approval, saying, “This is my favourite novel of all time.” It was an unusual enough choice that it whetted my appetite for anything else she might give the nod (I wondered if she was biting her tongue when I bought three novels by that jovial lager-lout, Keith Waterhouse, at one go) but nothing else I ever purchased from her elicited similar approval. But I did walk along with her for a couple of blocks on Dundas Street one day as she sang the praises of Agatha Christie for those times when you still want to read but are so mentally overloaded that you can’t risk taking on anything that will stimulate “the little grey cells”. Small risk of that with a scantily sketched Marple or Poirot. There is such a depth of insight into the complexities of the human condition throughout these three linked novels that I think of Sigrid Undset as the great anti-Christie. Undset was reportedly fond of an old, Norwegian proverb that goes: “Never take hold of the truth with mittens on.” And the details and complications, the social, political, familial and religious backgrounds that inform our knowledge of every character in this most highly regarded of her twenty or so books, indicate that this was one superlatively mitten-free writer. Her storyteller’s grasp is ever-alive to nuance and paradox. The primary narrative arc of the novel tells the life story – from girlhood to grand-motherhood – of a conscientious and God-haunted woman who enters a nunnery in her teens so as to postpone her arranged marriage to a decent man she doesn't love. In a chance encounter during a day trip from the convent, Kristin manages to fall under the spell of a disgraced and dissolute older man named Erland Nikolausson whom she does most recklessly love and eventually marries (while secretly pregnant), much to the disapproval of virtually everybody in her life, including her own thoroughly conflicted self. The clear dictates of logic and religion having been jettisoned by sexual passion and impulsive personal choice, we watch, both enthralled and appalled, as these two incompatible yet irrevocably smitten souls struggle to work out their destiny together. Watching them contend with the lifelong difficulties and challenges that grow out of their rash conjunction, there was another old anonymous proverb – this one Spanish – that repeatedly popped into my mind while reading this book: “Take what you want,” said God. “Take it – and pay for it.” While Erland has an undeniably seedy past to live down and his every manoeuvre in the early sections of their saga rouses the reader’s suspicion and dread, he gradually comes to embody a touching integrity in his simplicity and directness. Yes, he can still get into trouble when he reacts too impetuously or says too freely what’s really on his mind. But he rarely operates out of malice or pettiness or a will to manipulate or deceive. More instinctively, completely and easily, he seems to fulfill some of those Christian dictates that Kristin far more self-consciously labours to uphold herself and instill in others. A number of Undset’s earliest successes as a novelist told the tales of sassy, urban proto-feminists. It was her extensive research into Norwegian history that led to her Catholic conversion in 1924 and she subsequently regarded many of those early novels as “immoral”. I’ve not had the opportunity to read them but find it hard to imagine that any of them could possibly present such a comprehensive woman’s eye view of the world as Kristin Lavransdatter. Undset's ten-page description of Kristin’s first of seven childbirths – all boys – was an immersive revelation that had this male reader crying out for an epidural and a mouthful of crushed ice to suck on.

For its engrossing depiction of an entire alternative universe in Undset’s rich portrayal of pre-Reformation Norway, David Warren called Kristin Lavransdatter, “Tolkien for adults”. Reading how powerfully influenced Margaret Mitchell was by Undset’s saga when she wrote her one and only novel in 1936, I also think of Lavransdatter as Gone with the Wind for adults, with Scarlett O’Hara standing in as a cardboard cut-out for Kristin, Rhett Butler for Erland and Ashley Wilkes for the decent fiancé Kristin spurns, Simon Darre. In consultation with Undset in the last year of her life, A.H. Winsnes wrote his critical study of her life’s work, Sigrid Undset: A Study in Christian Realism. In its summary chapter, Winsnes wrote: “What is at issue in her imaginative writing, or for that matter in all of her work, is the question of loyalty. Her novels do not put problems to debate – there is no over-riding bias; they are not doctrinaire in that way. But they answer the question: What is loyalty? In what does the essence of loyalty consist? Can human beings be loyal to each other? . . . The conflict of conscience which results from disloyalty – the conscience tormented and the conscience saved – is the theme which constantly recurs. For this reason, her writing revolves around the central relationships in life in which loyalty is demanded, wherever a pact must be kept or service rendered – between husband and wife, parents and children, the individual and his home, family and country. Most of all it is concerned with man’s loyalty and disloyalty towards the Creator, for without loyalty towards Him, no other loyalty is possible.” Not too surprisingly (how else could she have gained such insight into the mischief that intimate misalignment can wreak?) Sigrid Undset’s marriage to the artist A.C. Svarstad seems to have been just as tempestuous and riddled with strife as Kristin and Erland’s. But this never caused her - as an author or a wife - to jettison personal difficulties by writing off the other as the sole source of trouble. Imperfect and precarious as Kristin and Erland's union may be, there is never a denial of the love they feel and the need they have for one another. As a hugely influential public figure whose visage would one day turn up on the national currency, it was widely noted that Undset had repeatedly spoken up against the Nazis in the 1930s. Her books were summarily banned when the Nazis took over as occupiers and in fear of her life (one of her sons was killed in a concentration camp) she was forced into exile in her late 50s, travelling to San Francisco via Sweden, Moscow, Siberia and Japan in the spring and summer of 1940 and keeping up her resistance work by writing magazine articles and doing radio commentaries with the Norwegian government in exile. When she returned to her beloved home just outside Lillehammer at the war's end in August 1945, she was notably depleted and put fiction writing aside, investing all her remaining energies into writing her final book, a superb biography of St. Catherine of Siena that was published shortly after her death.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed