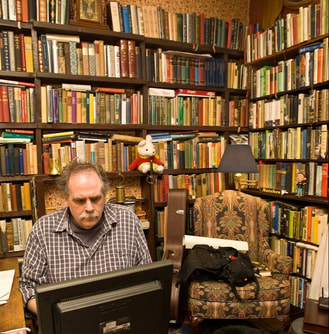

LONDON, ONTARIO – Life got in the way this week, so here’s a little talk I delivered to the Baconian Club of London almost exactly fourteen years ago: A dream I had in my late twenties strongly suggested that my predilection for reading was getting out of hand. My wife and I are carefully navigating King Street just west of Clarence during a rush hour dusk when I see a beautifully illustrated book lying open right there in the middle of the road. Though I can scarcely make out the words in the falling light, I apprehend that the great secret to life I’ve urgently been tracking is contained in those pages. Paying no attention to the bumper to bumper congestion all around us, I drop to my knees to ferret it out and my wife pulls me up by yanking on the collar of my shirt. “Before you crack that little tome,” she reasonably suggests, “perhaps we’d better get off the road.” At a Labour Day barbecue about ten years ago, my sister-in-law nodded me over for a quiet aside, her face suggesting that she was becoming concerned about my mental health. “I saw you biking down Dundas Street last week,” she said, pausing to phrase the next part of her inquiry as judiciously as possible. “And it looked like you might have been reading a book? You weren’t really, were you?” “That was Wednesday when they put out the new arrivals cart at Attic Books,” I explained. “I finally found Ronald Knox’s Essays in Satire for $7.50. Do you have any idea how long I’ve been looking for that book? So, yeh, I was reading it a little. I was watching the traffic too, though. Oh, come on,” I said as she backed away as one from an alien repulsed. “Haven’t you ever felt that way about a book?” Apparently not. About five years ago I was talking with a friend who was depressed out of his gourd by the forty-minute commute he had to make to and from work each day by bus while his wife took their car. “I’d kill for eighty minutes a day on the bus,” I said with perfect sincerity. “That’s a wonderful opportunity you’ve got there. Do you realize how much reading you can get done?” This didn’t ameliorate his distress whatsoever. In fact, my suggestion irritated him and I realized, not for the first time, that all are not constituted as I am. For that matter, nor was I, at first. First of all I remember the sound of my parents reading to me in bed, intoning the words with just enough expression to convey the sense of the story without repelling the advance of drowsiness. I remember hearing both collections of the Winnie the Pooh stories by A.A. Milne, perhaps Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and apparently Helen Sewell’s Black Beauty. I say ‘apparently’ because I could’ve sworn that the first time I ever read it was in the late ‘80s, one chapter each night to my son Hugh. I enjoyed it then though I was a little taken aback at how many of the chapters seemed to be little more than lectures on temperance from the equestrian perspective. But when we were moving our parents out of the old family home on Wortley Road in the spring of 2000, I was put in charge of winnowing their music and book collections. And I came upon a badly battered edition of Black Beauty with my name on the flyleaf written in my mother’s hand. I suspect my tee-totalling Gran (being married to an alcoholic can do that to you) probably gave it to me for Christmas. Perhaps I’d said something about wanting a pony and this seemed a reasonably priced alternative. I don’t recall that my parents read to us habitually or even frequently. It seemed to come in waves, probably as part of an occasional campaign to reinforce the idea of a stricter bedtime regimen. I remember both of them, perched on the end of one of our beds and holding forth from time to time, maybe my father a little more than my mother because his facility with words and language was so easy and natural. I feel quite certain it was the kind of thing that Mom would’ve put him up to, however; explaining that it was good for us. And so, by gum, it was. Neither one of my parents were big readers. Mom would occasionally take up recent bestsellers of a religious nature. Catherine Marshall’s memoirs of her pastor-husband, A Man Called Peter, was a big hit with Mom, as was Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Slightly more surreptitious were her excavations in tomes of prophetic hokum by Edgar Cayce and Jeane Dixon. Her standards weren’t high or particularly sophisticated but she rightly sensed she was slumming with those goofs. Jack regularly knocked back his daily London Free Press and his weekly Time magazine but books were few and far between with him. I know he read John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley because he marvelled repeatedly at what a slight and fluffy thing it was. I fear that he let that experience put him off giving other books much of a chance for a decade or two. (An interesting reversal of that stand-off took hold late in his life when he approached books warily because they made him feel too much. The poetically apocalyptic prose of Anne Michaels’ novel Fugitive Pieces had him crying on page one and he set the novel aside because he just couldn’t bear it.) Those parental story-telling sessions prepared the way for similar readings in the lower grades of primary school. Whenever the teacher put aside the lessons and drills of elementary tutelage and instead took up our book of the month for ten or fifteen minutes of pure recreational reading, everything about school changed for the better. With no nagging requirement to analyse or regurgitate anything, the usual tedium of the classroom was magically lifted away as if some oppressive ceiling that ordinarily cramped our vista had suddenly been opened up to the sky. It was the splendidly named Miss Mitten who introduced me to Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, a sublime book that pulls together all of the most potent strains of English children’s writing. There’s not only the irresistible whimsy of talking animals, these ones also drive cars and hijack trains. To this day I practically levitate with the snug-as-a-bug cosiness of the Christmas Eve feast at Mole End, complete with a passel of carolling field mice. And then, lest this tale become too static in its contentment, there is the distinctly unsettling pantheistic mysticism of that otherworldly chapter called The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (a title Pink Floyd aptly nicked for their very first psychedelic platter). Miss Mitten, bless her heart, had read us a book aimed well above the heads of most of her seven-year-old students. The story could be listened to quite profitably but it was beyond my own reading comprehension as I discovered not too long after when I took out my first few books from the Fred Landon Library on Wortley Road. Right in the very first paragraph, I was flummoxed by the third sentence, “Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing.” What? Come again? Far more accessible, though still a challenge, was to revisit Winnie the Pooh which opens, “Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head behind Christopher Robin.” That was more like it. This summer I read, On Englishing The Bible, by Monsignor Ronald Knox, describing the challenges he faced in the late 1940s as he worked on his modern English Catholic translation of the Bible taken afresh from the Latin Vulgate. In one passage Knox writes, “Words are not coins, dead things whose value can be mathematically computed . . . Words are living things, full of shades of meaning, full of associations, and, what is more, they are apt to change their significance from one generation to the next. The translator who understands his job feels, constantly, like Alice in Wonderland trying to play croquet with flamingos for mallets and hedgehogs for balls; words are forever eluding his grasp.” I would say that Knox’s simile just as vividly conveys the awkwardness of every aspiring young reader who must learn how to navigate his eyeballs across a page covered in row after row of inky black marks. First he must cast his eyes in such a way as to discern those marks as letters, then divine the words each clump of letters represents, and then grab hold of the developing flow of a narrative as he scans his way along a whole series of those clumps. For any sort of pleasure to arise, all these processes must be undertaken in rapid and unconscious succession like a string of intricately co-ordinated firecrackers that sets off explosions of meaning in his brain. I remember my own big breakthrough. It was an autumn evening in my seventh year, sitting cross-legged on my bed in a brand new pair of fabulous smelling flannelette PJs when I was finally able to more or less read, Chapter One: “In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie-the-Pooh and Some Bees, and The Stories Begin”. After years of imbibing the alphabet with only patchy, rudimentary comprehension, my flamingos suddenly started to connect with my hedgehogs with wonderful frequency and I got the hang of it, the sense of it. For the first time reading wasn’t an activity I took on trust as something I would come to enjoy some day. That night I tasted the sheer independent joy of reading for oneself, and felt the amazing rush of pride and elation as I pushed off from shore in my own little craft and somehow stayed afloat on this vast sea of words. Though my progress was swift and instinctive and I quickly became known as the class’s best speller and a reader who could be counted on to read aloud with intelligent expression, it would be another fifteen years before reading joined breathing, eating and sleeping on my biological must-do list. There were months, indeed whole seasons, as a kid when I didn’t read anything that wasn’t required for school. And far more often than not, when I did take up a book, it was tripe. I read a few instalments of the Hardy Boys series but soon tired of their formulaic pseudo-sleuthing. I found the Enid Blyton Adventure series a little more engaging. While her characters were cut from the same bland cardboard as Franklin W. Dixon’s – Kiki the Parrot is the only one who still resides in my memory with any vividness –the English milieu and references were a little more exotic and engaging. I also knocked back most of Beverly Cleary’s Beezer and Ramona oeuvre. I was initially drawn to try one out because my best friend also happened to be named Beezer. In reading these contemporary tales of small town American life involving paper routes and dogs and birthday parties gone wrong, I discovered that unlike most of my male friends, I didn’t require guns and explosions and heists to hold my attention. A few years later when Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels were being greedily read by some of my faster moving friends (and particularly treasured for all the naughty bits where Bond has his way with voluptuous foreign agents), I was not even momentarily attracted. Insightfully rendered stories of everyday life were quite compelling enough for me. The magic of my favourite kind of writing wasn’t that it showed me something I’d never seen before, but that it showed me something I thought I knew well in a much different or richer way. We are talking here about a period in the development of readers when – short of Mein Kampf or pornography – it frankly doesn’t matter much what a kid reads. If a kid enjoys stupid, hokey, sentimental or sensational trash, leave him to it, say I. I’ve long championed the now criminally neglected literary biographer, Margaret Lane, whose books on the Brontes, Samuel Johnson, and Beatrix Potter are second to none. In a wonderful essay collection called Purely for Pleasure, she writes about a boys' sci-fi shocker called The Wolf Men that she discovered as a child and couldn’t put down even though it traumatized her. The tale and its cheesy illustrations left her face "bathed in tears of voluptuous terror," she deliciously writes. Lane wisely counsels that we shouldn't apologize for "these first responses to bad literature [which] are fresh and genuine, and often, by contrast, prepare the way for more rewarding tastes when the time comes." Later at public school there was Edith Nesbitt’s The Railway Children, Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book stories and in grade five we heard Frances Hodgson Burnett’s, The Secret Garden. We had just finished reading that book when the teacher announced that one of our classmates – a girl who figure skated with some distinction – was having to undergo more surgery for a broken leg that hadn’t properly healed and would be extending her hospital stay a little longer. Would the class like to send her a gift to cheer her up? After a few impractical or dubious suggestions had been floated by some of the kids – a pony, a hockey stick, a subscription to Mad magazine - I piped up and said, “Why don’t we give her the book we’ve just finished?” My suggestion was manifestly brilliant, so, of course, it instantly carried the day. Or so I believed at first. But the pleasure of having my idea taken up was mixed with a new kind of disquiet. The alacrity with which Mrs. Longfield fastened onto my suggestion, got the class to rubber stamp it and actioned it, convinced me that I had been set up. I mean, think about it. The book had already been paid for. She wouldn’t have to go shopping, or lay out any more money. All she had to do was wrap the sucker and send it off. The thing had all the built-in teacher appeal of a professional development day. This was obviously what Mrs. Longfield had wanted to have happen all of the time. And she had cannily trusted that some representative student of no originality whatsoever would step forth and suggest it. And that sap had been me. If I have subsequently wasted more time than was warranted in struggling too hard to do the unpredictable thing – and there have been times in my life when I fear that has been so - then I blame Mrs. Longfield. She started it. She made me do it. Though Mountsfield Public was part of the normal or secular school system, I remember listening to oodles of child-friendly retellings of the Bible stories by some first rate writers like Walter de la Mare and Pearl S. Buck. This was the late ‘50s and early ‘60s; the last historical moment when educators could still get away with such (by today’s standards) heavy-handed cultural indoctrination. Even worse, we regularly sang hymns in music class, including that gross incitement to take up arms against the infidel, Onward Christian Soldiers. Yes, and they made us recite the Lord’s Prayer every blessed morning too. My God, it’s a wonder any of us still have sufficient independence of thought to order our own doughnuts at Tim Horton’s. Because I was born in time to still be brainwashed in this way, I received something that no graduate of the secular system has been encumbered with for more than thirty years now. This is something that our educators seem to think the rising generations can get by quite adequately without, thank you very much. I allude to a passable grounding in, a more than glancing acquaintance with, the stories of the Old and New Testaments. These are the tales that constitute nothing less than the founding and forming meta-narrative of Judeo-Christian civilization itself. To be unfamiliar with these characters, themes, parables, metaphors and stories is to have many of the most exquisitely outfitted rooms in the mansion of Western art and thought closed off to you. I was shocked by how quickly and completely that tap at the end of the Biblical storytelling pipeline had been shut off. In my late twenties I was back in a secular high school reading some of my fiction to a senior class. During a question and answer period one of the students wanted to know if writers had to read a lot of books. I acknowledged that it had taken a while for the reading habit to really take hold of me, but that I now consumed books like Moses consumed manna. “Like who does what?” this same girl asked and I stared back in gob-smacked bewilderment to match her own. “You’ve heard of Moses, right?” I asked. ”He’s like God – or a son of god. Or something like that,” she replied vaguely. Her bored sense of disconnection with this story was such it might as well have hailed from some abstruse wing of Mayan mythology. “I think he was more like a second-cousin god,” one of her classmates joked. His eye-rolling exasperation suggested he was one of very few people in that room who had any sort of grip on who Moses actually was. That was when the teacher intervened, hoping to nip this humiliating exchange in the bud. I wonder if she also felt some implication, some blush of tutorial negligence regarding the part she and her colleagues played in depriving these students of a workable cultural foothold. As I poked around in my distracted and desultory way en route to becoming a constant reader, I occasionally happened upon various mind-shaping books that went much deeper than the others. Among these in my teen-aged years were A Separate Peace, by John Knowles, The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley, Bright Day by J.B. Priestley and Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse. I’m constantly foisting these four coming of age novels on young relatives who loved J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and don’t know where to turn next. I think all four of them do at least as good a job as Salinger of tapping into endearingly vulnerable male egos undergoing various processes of construction or assault and manage to tell far more gripping stories while they’re at it. For a beautifully rendered distaff variation on the coming of age novel, I now recommend my recently discovered treasure of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle. I also happened upon an American edition of Richard B. Wright’s very first novel, The Weekend Man, remaindered for ninety-nine cents at Coles and read it in one delirious go, thus commencing my nearly four decade long campaign to spread the good word on my favourite Canadian writer. Wright’s greatest strength has always been the uncanny verisimilitude of his storytelling – both the all too credible incidents he writes about and the flawlessly natural prose in which his tales are rendered. His stories of contemporary Ontario life are routinely populated by likable, thoughtful, middle-aged types who never quite manage to take hold of the steering wheel of their lives; because of a complexity they can’t deny, a decency they won’t discard, or a wicked sense of humour that can’t be suppressed. His is an unflashy gift too readily overlooked in an age when the hyper poetic prose of a Michael Ondaatje or a Jane Urquhart tends to scoop up all the prizes. I was delighted a few years ago when Wright’s ship of good fortune finally came in for his ninth novel, Clara Callan. After decades of critical neglect and so-so commercial sales, he won every Canadian literary prize worth having. In addition to The Weekend Man and Clara Callan, I highly recommend his second novel, In The Middle of a Life, and his eighth, The Age of Longing. Those are the crème de la crème but in truth, there isn’t a stinker in the lot. And then there was Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, which taught me that the whole purpose of falling in love was – oh but of course! – to destroy ourselves. The entire scribbling Bronte brood (one sister, Charlotte, wrote Jane Eyre and three other novels; another, Anne, wrote The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Agnes Grey) is well worth reading but it is Emily’s only and very singular novel, Wuthering Heights, that really takes the cake. This one-of-a-kind romance is populated with brutally vivid characters caught up in a love story that demolishes and consumes everybody who gets in its way. Bronte spins out a vision of such uncanny, elemental power that the wretched unhappiness of virtually every character in her book is of strictly secondary importance. Like a nightmare or a myth that throttles you in its grip, you hang on for the ride and don’t really stop to think that life’s not ordinarily like that. When the gods go a-courting, mere mortals run for cover. It didn’t hurt a bit that this most fevered of Gothic romances was urged upon me by my shapely, blonde and wonderfully encouraging grade ten English teacher for whom I’d developed a powerful yet utterly innocent crush. She was at least six years older than me and was a woman of the world who held down a real job so I knew there was no way we’d be running off anywhere together. But that didn’t mean I couldn’t adore her and strive to serve her and bask in her presence and make her laugh whenever possible. And it soon became clear that the best way I could maximize the opportunities for all of these forms of devotion was to write. I handed in something for her appraisal virtually every day and she kept up her end of the bargain without flagging. It’s a little painful, a little wince-making today to leaf through the dreck I turned out for her by the binder full – much of it strained and pretentious, self-indulgent and stupid. But ultimately, all that really matters is that she got me writing at a furious pace. I was soon cranking out volume after volume of short stories, novels, autobiography and poetry. Of course, it was mostly crap but I learned a lot as I went along and my stuff did incrementally start to improve. I was writing so much that I had precious little time left for reading. And this I have come to regard as a real blessing. A preternaturally sturdy ego that accounts for thirty per cent of my total body weight also probably helped out here. Let me explain myself. So long as one resists paralyzing self-consciousness and attendant thoughts of unworthiness, that ten years after the onset of puberty is the most fertile time in any budding artist’s life to take their undeveloped potentialities for a walk and see what turns up. During those same crucial years from the mid-teens to the early 20s, I have watched many potential writers with at least as much innate talent as I ever had, extinguish their own flames in two different ways – both the result, in my estimation, of reading too much too soon. Some were way too influenced by one favourite writer’s style and when they bashed out their own early experiments, they inevitably turned out work that read like a pale and affected imitation, and so quickly lost heart. I confess. I produced one “What I Did on My Summer Holidays” type report in shameless emulation of Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. My teacher knew what I’d done and wasn’t impressed. I knew I’d sold myself short and never resorted to such camouflage again. I’d only been taking a couple of part time literature courses anyway and by the following spring, I’d quit school altogether. Then there were those friends who went on to university and immersed themselves in a wider range of excellent writing. Finding all of it to be so completely beyond their own capacity to match or add to in any significant way, they too became discouraged about pushing along their own unworthy projects. By constant comparison with the great work of others, they recognized how great their own work wasn’t and decided they had to learn a lot more before they would presume to put their own stuff out there. Some of them believed that once they’d earned their degrees, then they would have the confidence to let it rip but I have rarely seen that strategy pan out. That usually turned out to be just the first in a series of way stations on the road to Never-never-land. Once my student loan’s paid back, once we get married, once the kids are in school, once the divorce comes through, once I retire, once I get hit by lightning, once I get reincarnated as Graham Greene. Because I only read fitfully and erratically at this time, I was not cursed with the dismal knowledge that virtually every published writer on the planet was better than me. A part time dishwasher’s wages also helped out here in that when I did buy a book, I avoided expensive new bestsellers and contented myself with the neglected dross of previous generations that I’d pick up for a pittance from Sally Ann and Goodwill stores. With the glitter of newness and the haze of hotness all worn away, I still found much to admire in such solid, journeyman authors as John Steinbeck, J.B. Priestley and Somerset Maugham. I learned a lot from these craftsmen and best of all, I never had my head turned or my instincts dulled by being tempted to emulate the latest literary crazes and fads. So I had written a fair whack of stuff and had a novel and some early music journalism published, before constant reading really took hold of my life. Unlikely or inexplicable as it seems, the volume that heralded the breakthrough was Wilifrid Blunt’s, The Dream King, a biography of mad Ludwig II of Bavaria. This was a deluxe illustrated edition with lots of pictures of Ludwig’s ruinously expensive castles that I picked up for $2.99 at a sale of battered and soiled Penguins at Coles. I followed up this study of ruinous failure by coughing up the full price for a paperback edition of Margaret Lane’s biography of the doomed Bronte siblings, The Bronte Story. This has got to be the saddest real life story in all of English literature as you watch one remarkable genius after another get cut down as tuberculosis slowly and intractably stalks their household. Was it any wonder that Wuthering Heights was so pitiless a book? These tragic biographies not only gripped me, they also supplied a sort of solace; simultaneously warning and reassuring me that neither genius nor high birth, talent nor industriousness, were guarantees of happiness or success. While there were things you could do to augment your luck should Dame Fortune ever turn her gaze your way, life was one big crap shoot where the very best work would often fail to be taken up by a larger public. So be it. Either way, I would never be sorry if I managed to follow my own curiosity and affirm the truth as I understood it, both as a reader and a writer. I first  read James Boswell’s now two hundred year old Life of Samuel Johnson the year I was married and have revisited this sprawling and affectionate account of a great soul’s life every few years since. I found that I could not only enter the world of Queen Anne with ease, I loved the whole milieu and longed to live there. Remembering my struggles in high school reading Shakespeare cold on the page (seeing or just listening to a play was something much more congenial), I’d anticipated some resistance but there was none of it. This was the book that first enabled me to lift myself up over the rim of the twentieth century and completely connect with an earlier time. And what a relief it was to finally shed the arrogant and barbaric conceit that contemporary human beings are inherently smarter than, or substantively different from, our forebears. Perhaps its appeal is strongest to we Grub Street hacks and drudges of a later era but anyone who’s ever heard the pub clock chime its closing knell and wished that conversation with friends didn’t have to end so soon, will find heart-warming consolation here. Boswell’s near miraculous portrait presents Johnson in his fullness and occasional smallness, at his wisest and at his silliest, at his noblest and at his most pathetically touching. Success with Boswell’s Johnson, naturally, emboldened me to take another run at Shakespeare with similarly expansive results. I can now extract the sense from the page if I absolutely have to but feel no shame about augmenting my reading with a good crib, or better yet, seeing a production on stage or screen. Whenever we attend a play at Stratford, I read aloud to my wife on the way down from The Friendly Shakespeare – an ultra-accessible guide to almost all of the plays by Norrie Epstein, a University of California lecturer. Once I became conversant with a sampling of the more popular plays, I could only join the universal chorus of praise and exaltation and marvel at the range of this one man’s sympathies and insights. Contrast the aching romanticism of Romeo and Juliet with the iron-in-the-soul pessimism of King Lear; the moon-drenched hilarity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with the oppressive menace of Othello or Macbeth. The great psychological motherlode of Hamlet juggles more themes than most playwrights tackle in their entire careers. The only printed document that beats a script of Hamlet for more perfectly polished aphorisms to the page is a copy of Bartlett’s or the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Even his more obscure plays are amazingly rich and relevant. If he’d only written The Winter’s Tale, he would deserve to be remembered and produced today. Any Canadian who lived under Pierre Trudeau will recognize the dynamics at work in Coriolanus, which portrays the fall of a brilliant leader who’s too proud to flatter the masses. It was in my early years as a father, seeking out material to read to my kids, that I first latched onto Walter de la Mare. When he’s remembered at all today, de la Mare is regarded as a children’s poet and storyteller, and he was both of those, superbly and daringly. He also wrote poetry for adults, in the same class as Yeats, I would say, but without the self-conscious flakery and obscurity of all that Celtic Twilight twaddle. His ghost stories are delicately menacing and irresistibly intriguing and virtually all of his fiction is, in one sense or another, haunted. – either by dead people or the shadow of the living God whom he can never quite believe in nor safely ignore. Perhaps the greatest of all his creations are his brilliant one of-a-kind anthologies of other writers’ work. He compiled two superb collections of poetry – one for very young children, Tom Tiddler’s Ground, and one for older children (which today, I’m afraid, makes challenging reading for many adults) Come Hither. W.H. Auden, a dab hand at poetry, criticism and anthologizing himself, deemed Come Hither “the best of all anthologies for the young.” Nearly half of Come Hither’s eight hundred pages are devoted to wonderfully arcane and illuminating footnotes, a pattern of construction that he repeats in much of his other work of this kind. The anthology Behold This Dreamer! is subtitled Of Reverie, Night, Sleep, Dream, Love-Dreams, Nightmare, Death, the Unconscious, the Imagination, Divination, the Artist and Kindred Subjects and quite miraculously, de la Mare mentions Sigmund Freud a grand total of once and Carl Jung not at all. Love, is a collection of poetry and prose celebrating that most divine and multifaceted of all our emotions. And my very favourite of his anthologies is a great grab bag of poems and musings on earliest childhood, Early One Morning. De la Mare said he was exasperated by reading memoirs by professional men and even certain dim-eyed artists where we find our main subject is smugly seated on the train up to Oxford by page five. Reacting against such criminal obtuseness, he pulled together this collection which he dedicated to his conviction that, “The life of childhood, if it is pondered over closely and heedfully, is as wide and various, as strange and mystifying as human nature itself. It is a vast landscape seen at daybreak.” Considering I quote him somewhere in about every tenth article I write, I suppose I have to at least acknowledge here the impact of G.K. Chesterton on my life. His genius for parallelism, paradox and wordplay infuses everything he writes. One of my very favourite Chesterton quotations hails not from any of his books, but was thrown off in the heat of a debate with George Bernard Shaw about the female enfranchisement movement. “Twenty million young women rose to their feet with the cry, ‘We will not be dictated to!’ and promptly became stenographers,” he said – just like that. It was Chesterton more than any other single writer, who called me on my perpetually postponed standoff with Christianity, and dragged me – not quite kicking and screaming – into the Roman Catholic Church at the age of thirty-two. If you have any use at all for apologetics, you’ll find none better in the English language than the two linked volumes, Heretics and Orthodoxy and his Christian response to H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History, The Everlasting Man. His jubilant biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas (subtitled The Dumb Ox) were profoundly admired by some of the most hard-assed Catholic scholars on the planet, like Etienne Gilson and Anton Pegis. His literary criticism on view in Charles Dickens, A Critical Study and The Victorian Age in Literature, and his art criticism, solely contained in a short, early volume on the now all but forgotten allegorical painter, G.F. Watts, is some of the most exciting and insightful literature of its kind. I can’t really explain why it finally happened when it did but by my mid-20s, the shift was total. And I’ve been fascinated to see that as my children similarly move into their adult years, they are repeating the very same pattern of behaviour. Whereas I used to squander nearly all of my mad money on records, practically overnight that fund was substantially reallocated to books. With music, I was always collecting the newest releases but with literature my fascination often drew me further and further into the past. To my surprise, the more I read, the more conservative I was becoming. By trading in pop stars for authors as my leading cultural lodestars, books were making me less slavishly preoccupied with the time I happened to live in, less embarrassed by the prospect of growing older or even growing up. Records I had always arranged alphabetically. Books – at least all forms of fiction, poetry and plays and collections of essays - I arranged chronologically by birth of authors. Thus some rather startling revelations emerged on my shelves. For instance, that perpetual, alcohol-addled roaring boy Dylan Thomas was a precise contemporary of the well-upholstered Robertson Davies. Now, what does that do to your mind? Isn’t that sort of fun to think about? I have occasionally championed authors at the same time as they’ve enjoyed popular favour. American novelists Anne Tyler and Richard Russo spring to mind here as well as English biographers Richard Holmes, Peter Ackroyd and A.N. Wilson. When I tackled George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien I was reading mid-twentieth century favourites whose broad readership has been steadily maintained throughout my life. With my more recently developed love for the mysteries of Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers and Josephine Tey, I’ve enjoyed that lively sense of cultic camaraderie that virtually all mystery writers seem to inspire among their readers. And as special anniversaries or important new biographies come along, I’ve been but one constituent in wider waves of revived interest in such classic authors as Anthony Trollope and P.G. Wodehouse. But far more often than not, I have happened upon favourite authors by following my own instincts and interests. I’ve already made my case for folks like G.K. Chesterton, Walter de la Mare, J.B. Priestley, Margaret Lane and Keith Waterhouse who’ve churned out entire shelves of books I’ve devoured and enjoyed and whose names almost never see print in critical or book review journals. Then there are a few even more invisible one-off writers whose works I champion. Welsh writer, Richard Llewellyn, wrote a lot of novels that have perhaps rightly disappeared from our cultural radar screen but his How Green Was My Valley deserves to be remembered and read. His portrait of the inner workings of a remote nineteenth century Welsh mining village is fascinatingly rich and strange. It was the illustrations by N.C. Wyeth that first drew me to Charles Nordhoff and James Hall’s Bounty Trilogy. This is a magnificent achievement of research and imaginative writing that tells a mythic story that compares in many ways to the story of Adam and Eve and the fall of man. There have been popular movies of these last two works that barely suggest the power and scope of the books. And far more obscure than either of these, a few years ago at a seaside bookshop in Aldeburgh, England I picked up Under an English Heaven by the utterly unknown Robert Radcliffe which I regard as the finest World War II novel I’ve ever read. Radcliffe, a retired pilot, sets his tale among the American bomber bases scattered throughout East Anglia. My brother in law once took me on a tour of some of these abandoned and now overgrown airfields from which armadas of American bombers headed out across the North Sea, through occupied northern France and into Germany on daring, daylight raids which could exact horrific ‘attrition rates’. In addition to some incredibly vivid descriptions of warfare, in quieter segments Radcliffe beautifully captures the instinctive affinity – mingled with head-shaking incredulity - that exists between North Americans and the English. In one scene an entire village turns out en masse late one evening when the fish & chip shop – closed for three years due to war shortages – suddenly receives a contraband load of cod and fires up the fryers. One of the Yankee airmen writes home to his parents: “It was truly magical, all the villagers just standing out in the road eating their fish and chips in the moonlight together, smiling and laughing, even singing some in hushed voices. It was like there was no war, no hardship, no rationing, like they had no cares in the whole world. Just for a few minutes I felt real privileged to be invited along. A little homesick as well I don’t mind admitting though I’m not sure why.” By forcing it upon a librarian friend who concurred with my estimation, there is now a lone copy of Under an English Heaven circulating in the London Public Library system. Johannes Gutenberg invented the most sophisticated time machine that any of us will ever need in 1456 when he developed the first printing press with moveable type. Completely wireless and battery-less, it can be operated from your easy chair or the bathtub, from your bed or a blanket spread out on the beach, from a cramped seat on an airplane or with one hand gripping the overhead bar on the Oxford bus at 5 p.m. In an essay on books and gardens in his 1863 collection, Dreamthorp, Alexander Smith writes: “Books are the true Elysian Fields where the spirits of the dead converse, and into these fields a mortal may venture unappalled. What king’s court can boast such company? What school of philosophy such wisdom? The wit of the ancient world is glancing and flashing there. There is Pan’s pipe, there are the songs of Apollo. Seated in my library at night, and looking on the silent faces of my books, I am occasionally visited by a strange sense of the supernatural. They are not collections of printed pages; they are ghosts. I take one down and it speaks with me in a tongue not now heard on earth, and of men and things of which it alone possesses knowledge. I call myself a solitary, but sometimes I think I misapply the term. No man sees more company than I do. I travel with mightier cohorts than ever Timour or Genghis Khan on their fiery marches. I am a sovereign in my library, but it is the dead, not the living, that attend my levees.” Here Smith has identified the abiding blessing and miracle of books. Infatuated with (or enslaved by) instant communications as our own age is, it sometimes seems we are in danger of forgetting what we already have and too often take for granted in these technologically primitive documents. But give any of us a week at the cottage or even a few days recovering from a not terribly debilitating illness, and we remember. Give us a stretch of undistracted time when we cannot be pestered by mundane concerns and can really give ourselves over to the richest and most rewarding aesthetic experience possible, and what do we inevitably do? Turn on the TV? Surf the Internet? Fire up the Playstation 2 system for a round of Grand Theft Auto? No. We reach for a book. And if we’re lucky and we’ve chosen it well, we utterly lose ourselves therein and return from our hedgehog and flamingo-propelled voyage refreshed, informed, and sometimes even transformed. I expect it’s time, or even past time, that I wrapped this opus up. If I’ve whetted your interest in a book, or a few dozen books, then good for me. That’s what I set out to do. During the past few months as I’ve reviewed my personal history of reading and plugged away at this talk, I’ve reacquainted myself with a lot – but by no means, all – of my favourite stories and writers. While this has made me appreciate what a very well-stocked head of books I carry around on this neck of mine, it has also highlighted for me how much more there is for me yet to read. While I’ve read oodles of Trollope and all of the Brontes, I’ve barely touched the oeuvre of that smoking, belching narrative factory known as Charles Dickens. While I’d wager money that I’m the only person in this room who’s actually read Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, I blush to admit that I’ve only read the first book of Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. While I’m coming to terms with the likelihood that I may never read Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, I’m not ready to forswear Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary or Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. And my acquaintance with the great Russian writers is so criminally slight that it ought to be punishable by imprisonment in a cell well-stocked with Dostoevskys and Tolstoys. In other words, it’s time for me to stop talking and get reading.

2 Comments

Sue Cassan

21/9/2020 08:45:25 pm

What a great account of a long history with books. For those of us who find that keeping company with books is one of the eternal pleasures of life, this article expresses what we experience when the email comes from the library or bookstore saying the long awaited book is in. Then there is the incomparable pleasure of opening the book and reading the words, Chapter One. Best of all, is the uncanny arrival of just the right book at just the right time so that it speaks to you as though it was written for that sole purpose. Just as all dogs go to heaven, all the walls there will have shelf on shelf of books and more books, making the place absolutely perfect. Good for you for writing this paean of praise for the joys of the book.

Reply

Marlene Stoez

21/9/2020 08:46:56 pm

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed