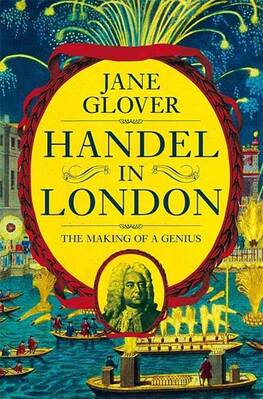

LONDON, ONTARIO – During the car ride up to Latin Mass in St. Thomas yesterday, I kicked off our 2019 edition of the Christmas season perhaps one week earlier than I can usually get away with it. “I’m writing about it,” I said by way of belligerent explanation that brooked no objections, slipping the first disc of Handel’s Messiah into the car’s CD player. I blame this uncouth jumping of the Christmas queue entirely on Jane Glover whose magnificent, Handel in London (2018), I just finished reading last week. Glover, herself a conductor and director of the Glyndebourne Touring Opera and the London Mozart Players, has wonderfully expanded my appreciation of the German-born George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) whose formidable industry and gift for invention did so much to help England forge its own musical identity. As a music professional Glover writes that “Handel has indeed occupied a sizable portion of my activity and my repertoire.” While she brings an insider’s perspective gleaned from hands-on experience with dozens and dozens of Handel’s operas, oratorios, anthems and orchestral works – and is able to combine that with her own wide reading and historical research – she still manages to tell a story which remains wonderfully accessible to the layman. Though Handel’s surgeon father allowed the boy to take his first lessons in music, he was leery of the facility and passion which the young lad displayed. Like so many parents, he feared the unlikely prospects of his son ever managing so unorthodox a talent – however precocious and pronounced it might be - in a way that would be congruent with steady financial sufficiency. I remember in grade three being haunted by a commonly reproduced illustration that a visiting music teacher showed us of a young George Frideric in his nightshirt being apprehended by a lamp-bearing father who has caught him tickling the keyboard of a banished clavichord in the attic in the wee hours of the morning. Glover reports that while the scene as portrayed almost certainly never happened, Handel’s father insisted that his son's primary vocational training was focused on some field other than music.  The apprehended musical night owl The apprehended musical night owl At school Handel was diligently preparing himself for a career in law and keeping up all of his musical activities on the side. Even though his father died when he was twelve, Handel kept up his non-musical studies until the age of 17, when he moved full time into the pursuit of a musical career. Greatly benefiting from all of that paternally administered cautiousness and his his own solid grounding in legal principles, right from the get-go Handel was remarkably adept at securing contracts and sponsorships. In a field of endeavour where so many great talents get taken advantage of and exploited, even as a teenaged prodigy Handel had an innate nose for business and an unerring eye for the main chance; for what he could accomplish and what it was worth. While working as a second violinist in a Hamburg opera house, he had his first opera professionally staged at the age of 20. And the very next year he was off to Italy where he rubbed elbows with Correlli, Scarlatti and Telemann and had two more operas staged in Florence and Venice. At the age of 25 he was appointed court conductor to the German House of Hanover and was invited that same year to write an opera to be produced in London. Then when a convoluted crisis in succession played out with Handel’s mainstay, the Duke of Hanover, being crowned the King of England as George I, everything came together quite spectacularly. For the rest of his life, this German composer would live and work in England specializing in – then all the rage – Italian operas. He sat on the board of governors of the opera house, he composed at least a third of the operas performed there, he recruited and trained the singers and players, adapting or swapping out various arias and songs to suit the specific talents of his performers. He also wrote music for state occasions – Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks being two of the most famous – as well as Zadok the Priest in 1727 for the coronation of George II. This spine-tingling choral hymn has been subsequently performed at every British coronation since then. I also treasure his dozen Concerti Grossi and the fifteen Organ Concertos which Handel himself would frequently perform between the acts of his operas and oratorios. In the final chapter of her book, Glover summarizes Handel’s career: “But Handel’s real legacy, to the infinite benefit of posterity, is his quite remarkable compositional output: over seventy dramatic works (operas and oratorio) and impressive lists of sacred music, secular cantatas, instrumental music and keyboard music. Throughout this massive oeuvre, quality is consistent. Handel was always individual and repeatedly of startling, exhilarating innovation; and although he was sometimes routine, he was never mediocre. There was no question of him ever resting on his laurels, or submitting to defeat if things went against him. If one door closed, he would find another straight away and march confidently through it. And the manner, too, in which he delivered his immortal masterpieces speaks of a supreme professionalism. In his assessment of singers, his building of teams, his challenging the supremely gifted to even greater heights, to their glory as well as his own, his accommodating weaker components with sympathetic skill, he was constantly vigilant and inspirational. The preparation of all his musical material and the rehearsal of so much music – often at a pace, especially in his latter years, almost unimaginable – was staggeringly impressive. To be sure, he had around him the right people to keep his energies running. But there is no doubt that it was his own charismatic energy and fierce insistence on the highest possible standards that drove the whole machine.” Musicologist Michael Kennedy identifies Handel’s development of the dramatic oratorio – and of these most especially Messiah – as his “most original contribution to the art of music.” He devised the oratorio out of necessity because the London audience for Italian operas was suddenly and sharply fragmenting. It always had been a rather rareified art form that appealed to a select and wealthy fraction of the populace. And just as that support was starting to diminish, a second London opera company opened its doors which only further sabotaged the prospects of success for everybody involved. There always had been grumbling in the wider society about why London insisted on presenting operas in languages that most Londoners didn’t speak. That frustration greatly fueled the impact when John Gay premiered his wildly popular Beggar’s Opera in 1728. Featuring 69 adapted popular ballads in three acts and telling the stories of low-lifes, thieves and whores, The Beggar's Opera was as startling a gob in the face of the musical establishment as anything that Johnny Rotten ever expectorated in the general direction of progressive rock blowhards in the 1970s. It was time for Handel to introduce a whole new wrinkle to the musical proceedings. Within a couple of years he produced the world's first oratorio based on the Old Testament story of Esther. Referencing a story that was commonly known . . . rendered in a language that everybody spoke and understood . . . straightforwardly presented without ruinously expensive sets and costuming . . . and capitalizing on the English genius for choral music . . . in one perfectly brilliant and perfectly simple stroke, Handel attracted whole new audiences and infused new life into English music-making. And, apparently, he revivified himself as well. When Handel perfected his new musical form several years later with the composition of Messiah, setting a libretto supplied by his friend and colleague Charles Jennens, he wrote the entire oratorio in less than three weeks.  George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Jane Glover gives a wonderful account of the very first performance of Messiah in Dublin, Ireland on Monday, April 12, 1742. The 27 year-old soprano for that historic performance was glad to get out of England where she had become the subject of scandal by extricating herself from an abusive marriage with a little help from her brothers, one of whom was the rising composer Thomas Arne: “Susanna Cibber received an especial tribute,” Glover writes. “After she had sung ‘He was despised’, the longest aria in the whole work, combining sorrow, desolation, guilt and even rage, the Reverend Dr. Delaney of St. Patrick’s (and soon to be the husband of Handel’s friend, Mary Pendarves), leapt to his feet, crying, ‘Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven thee!’ If Susanna’s reputation as a fallen woman had followed her from London to Dublin, she had certainly received the most public absolution, and in the most august of circumstances. It is to be hoped that this brought her comfort rather than embarrassment.” In 1784 to mark the centenary of Handel’s birth, the third Hanoverian King, George III, and a philanthropic doctor named Charles Burney were part of a team who organized a Handel Festival in which more than 500 musicians at multiple venues took part, the whole thing concluding with a grand performance of Messiah in Westminster Abbey not far from Handel’s tomb. In his Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster Abbey which was published the following year, Dr. Burney concluded: “Handel . . . though not a native of England, spent the greatest part of his life in the service of its inhabitants; improving our taste, delighting us in the church, the theatre and the chamber, and introducing among us so many species of musical excellence, that, during more than half a century, while sentiment, not fashion, guided our applause, we neither wanted nor wished for any other standard.” On my last visit to England I spent an afternoon mooching around inside the Handel Museum on Bond Street. The museum is housed in the building where Handel lived for the last 36 years of his life. They’ve done everything they can to restore the three-storey home that he occupied to its 18th century state and outfitted it throughout with period furnishings. Concerts are regularly held there and most afternoons, students from a nearby music academy play recitals on an antique harpsichord. On the front exterior wall between two windows on what we would call the second storey and the Brits would call the first, is a blue, National Trust plaque which reads: “George Frideric Handel 1685–1759 Composer lived in this house from 1723 and died here”.  The Houses of Messrs Hendrix and Handel The Houses of Messrs Hendrix and Handel And believe it or not, right next door, and again between two windows on the front wall, is another blue plaque that reads: “Jimi Hendrix 1942–1970 Guitarist and Songwriter lived here 1968–1969”. Strange near-bedfellows, indeed. But there is at least one parallel between them that merits mentioning: England, and specifically London, refined each of their very different talents to its purest and most striking form. Stateside, the Seattle-born Hendrix had a career but nothing that ever would have netted him a plaque on a building. So perhaps you’re wondering whose rendition of Handel’s Messiah I popped into the car’s sound system to get Christmas of 2019 underway. My choice was a sentimental favourite, the now 24-year old set produced by London Ontario’s own Gerald Fagan conducting the 135-voice London Fanshawe Symphonic Chorus, the 35-voice Gerald Fagan Singers, the Concert Players Orchestra and featured soloists Leslie Fagan (soprano), Janis Taylor (mezzo-soprano), Mark Dubois (tenor) and Gary Relyea (bass-baritone). I remember I was reviewing the disc for SCENE magazine in December of 1995 and had phoned Gerry up with a few supplementary questions about the production process. That first disc was merrily spinning away on the machine in my study as we talked and midway through track 20, He Shall Feed His Flock, as the mezzo-soprano stepped back and his own daughter took over in her pure and soaring soprano, Gerry politely asked, “Could we just be quiet for a couple minutes?” When the song concluded he resumed with two more questions: “Can the kid sing or what? Now then, where were we?”  Leslie Fagan Leslie Fagan Yes, there was a brashness to Gerry Fagan in those days but – unlike some other choirmasters in town who sometimes struggled to capture a fraction of the notice that he attracted – I always found him engaging and endearing. Today when you have to keep an eye open to find out where you can catch a Christmas performance of Handel’s most beloved oratorio, it’s hard to appreciate the way in which Fagan and his musical consortiums all but monopolized the sizable Christmas Messiah market for about 25 years. Though only the first of Messiah’s three parts is concerned with Christ’s nativity and the work was originally conceived for and flourished as an Easter oratorio, its association with the Yuletide has been established for the better part of two centuries. Through most of the 80s and 90s and into the 2000s, the only way other London choirs could get some Messiah action to themselves was to mount a production during the Easter season when the appeal was much more limited. Always Fagan helmed at least one December performance with the big choir at Centennial Hall and a more intimate performance with the smaller chamber choir in the exquisite acoustics of St. Peter’s Cathedral. Routinely, concert presentations trim about a half hour out of Messiah’s second and third parts so as to bring the whole show in at about two hours. For a few years in the early 90s, Fagan also put on a complete and unexpurgated performance and also a do-it-yourself Messiah where audience members were invited to bring along their own scores and join in the singing on all of the beloved choruses. Between editing SCENE magazine and freelancing as a columnist and arts writer with The London Free Press, I frequently drew the assignment to preview Messiah presentations, usually focusing on that year’s roster of soloists. In 2004 I was given a little more space than was usually available to write something up for a quarterly called Christian Life in London, and gave Gerry a heads-up that if he wanted to dig into the deeper religious significance of the work, this was his chance. He did not disappoint. That year’s soloists were Mark Boucher, bass; Darryl Edwards, tenor; Anita Krauss, alto; and Donna Bennet, soprano. The Friday night performance at Centennial Hall was going to be his 100th gig as a Messiah conductor and Sunday afternoon at St. Peter’s Cathedral was going to be his 101st. Here are some excerpts from that article: Fagan remembers well when his choral mentor Elmer Iseler conducted his 100th performance. “I wondered, ‘My gosh, how could you possibly do the same piece that many times?’” Well, now that day is here for Fagan and the only thing he’s wondering about is the depth and breadth of Handel’s genius. Fagan has brought his battered and much annotated score to our breakfast interview. “Here’s an example of the kind of thing I mean,” he says, enthusiastically flipping open the over-sized book to page 106. “We have this phrase from Isaiah, ‘All we like sheep,’ and look, the notes are all together, everything is moving exactly the same way until we get to, ‘have gone astray,’ and look at the notes here – everybody wanders off their own way. Isn’t that amazing? That’s the gift he brings to this music. With the language, with the setting of the words, he creates these word pictures all the time. I’m humbled to be learning new things every time we perform it. What happens at rehearsal is I get to pointing out this sort of thing to my singers as a musicologist and we almost forget to rehearse.” Fagan says his thrust at rehearsals is twofold. “One is to get them through the technique of what I want them to do, but I also want to give them insight into each chorus, make them understand. For instance, here, look at this page,” he says now flipping through the book at random. ‘Who is this king of Glory? Who is this king of Glory? Who is this king of Glory?’ He asks that three times before you get the answer. He presents us with this sort of repetition in almost every chorus. Whenever that happens, it’s an obvious reference to the Holy Trinity.” Fagan flips over to a page in the Easter section. “‘Surely he hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows,’” he reads. “Now this is a mob scene so he has solid chords. Then he leaves those chords and goes to the chastisement where he starts to break things up. I mean, look at the angularity of the writing here when we sing, ‘And with his stripes.’ What’s going on here? Christ is being flogged, they’re cutting His flesh and each word comes with this sharp, cutting edge. But when we get to the end of that line, ‘And with his stripes . . . we are healed’, then it suddenly goes to legato with this wonderful rounded smoothness. The music itself is being healed, in a way. The man was a genius. Every year I’m bowled over by the inexhaustible brilliance of his writing and his setting of the text. And you have to remember, English was Handel’s second language which makes such sensitivity to the text even more phenomenal.” Fagan says there are 25-year veterans in his choirs who love to sing the Messiah every year because it’s a work that is so wonderfully challenging. “Except perhaps for one or two solos, the choruses are the most challenging part of the work. It’s not often that the choruses are harder than the solos. A choir has to work and work and work at them. It’s almost the exact opposite of opera. The final chorus takes six full pages to say ‘Amen’. It’s treacherously difficult but it says ‘Amen’ like it’s never been said before or since.” Fagan admits that another reason why his enthusiasm for Messiah never diminishes, quite frankly, is because audiences come out to see it like no other oratorio. The only other big choral work that comes remotely close in terms of enduring popularity is J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. “As a performer, of course, I want to perform for people who enjoy the music,” Fagan says. “They might come to it for many, many reasons. Maybe they like the choruses. Or they think Darryl Edwards is a good tenor. Or they’re motivated more by their faith and want to hear the Psalms and all the different sections from the Bible. For some people it’s just one of those things they do every Christmas like decorating the tree or mailing out a pile of cards. For as many reasons as there are people, both in the audience and in the choir, Messiah is enjoyed.”  Marlene and Gerry Fagan Marlene and Gerry Fagan Because Christmas music is something we return to every year throughout our lives, it eventually accumulates a formidable memorative power that is more pungent than some people are comfortable with. I don’t believe I’m morbid but I do admit that no small part of the appeal of Christmas for me is the annual opportunity it provides to commune with the beloved dead. To hear Messiah’s opening recitative of ‘Comfort ye, comfort ye my people,’ is to be sitting once again with my parents in the balcony of Metropolitan United Church on a December Sunday evening in the mid-1970s when I heard that beguiling refrain for the very first time and knew this was music I’d be avidly returning to for the rest of my life. In December of 1991, I was late to the ‘do-it-yourself Messiah’ that the Fagan choirs were hosting at Dundas Street Centre United Church because I’d been at the bedside of my dying father-in-law. The choirs and the singalong audience were well into Part Three, just beginning ‘Worthy is the Lamb,’ when Gerry sent me in with a lyric sheet to sit among the tenors and the basses. I remember thinking at first how wrong they sounded, how flat, but soon understood that no, they were singing it right. What was missing was the blend that comes from sitting apart from the choir in a hall or a church and hearing all the different sections at once. And then the next thing I knew, I was utterly engulfed in that great ‘Amen’. I remember being startled into something like an out of body experience by the power and audacity of all those male voices; the music just cascading all around me like a meteor shower. Like Gerry Fagan, Jane Glover also describes the Messiah's conclusion as “the finest choral ‘Amen’ ever written – tranquil and reverential at its beginning, and building through ingenious controlled counterpoint to a thrilling climax. Whether performed by 250 singers or just eight, this ‘Amen’ never fails to make an impact and triumphantly to express the conclusion of the world’s most serious and important story.” And this will be my first Christmas without my mother-in-law; the person in this world with whom I most shared my love for Christmas music and to whom I most longed to read out whole sections of Handel in London. We had about a ten-year run when I took her to the Fagans’ Sunday matinee performances of Messiah at St. Peter’s Cathedral where we always sat in the lectors’ section of the pews to the west of the altar. I'm looking forward to spending some time with her again in the month ahead, enveloped in the revivifying waves of this immortal music.

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

19/11/2019 06:39:04 am

May I flesh out a little of the background about Gay and the Beggars Opera? John Gay 1685-1732, was a popular Poet and dramatist, and a member of the Scriblerus Club. He invested all his earnings into the first great stock market scam; The South Sea Bubble. Briefly The South Sea Joint Stock Company was formed in 1711 after the Spanish War to help reduce the National Debt. It's purpose was to Monopolize the fishing and trading rights of the Pacific and the Americas, in the manner of the East India Company. In 1719 it began trading it's shares in a public-private partnership. Without ever making a profit or actually engaging in any activity but with the help of Walpole's government and certain members of parliament the shares soared. Over the following year they doubled and redoubled in a hysterical feeding frenzy until 1720 when the bubble burst, ruining John and the majority of investors, and almost bankrupting the Exchequer. But not the founders and their political friends, who made huge fortunes from insider trading and bribes.

Reply

M.Menear

21/11/2019 05:52:34 am

Music lovers inspired by this portrait of Handel can hear his Opera Agrippina on Met Live at Silver City in our London on Saturday, Feb. 29, 2020. at 12:00 noon (get your tickets at least 4 weeks before this date). This was Handel's first Operatic masterpiece which he composed at 24 years of age. It was first performed in Venice 1709 and ran for 27 performances. It was revived by Handel in London in 1733. It is the story of the mother of Nero (Agrippina) scheming against the Roman Emperor Claudius (her husband) to have her son succeed Claudius as Emperor. It is said that at the end of the last performance the Venetians shouted "Viva Il Caro Sassone!" - Long Live the Beloved Saxon. He indeed is still living among us.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed