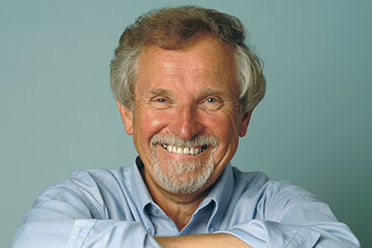

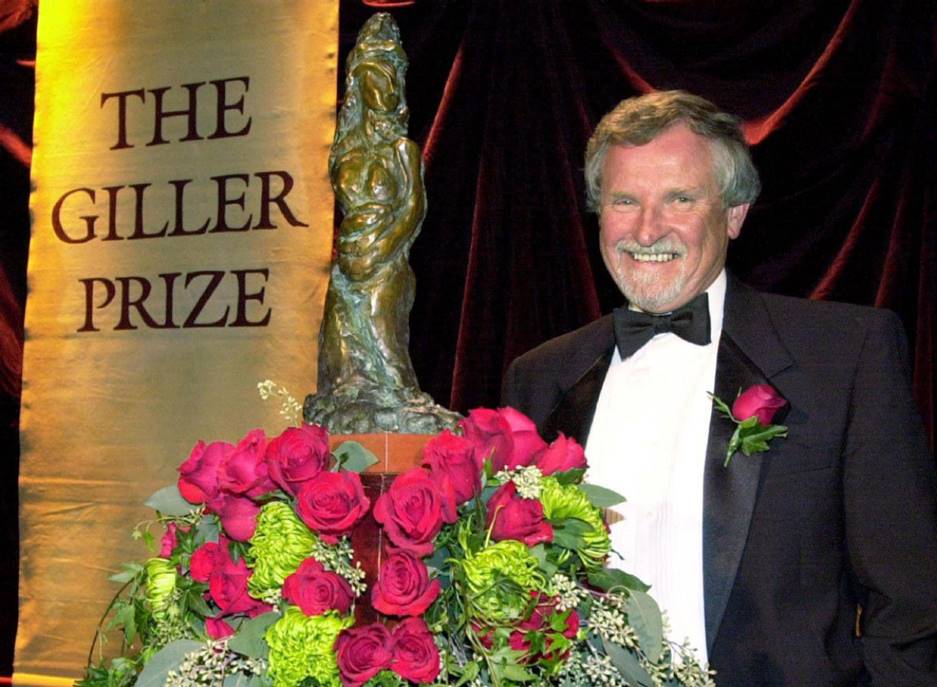

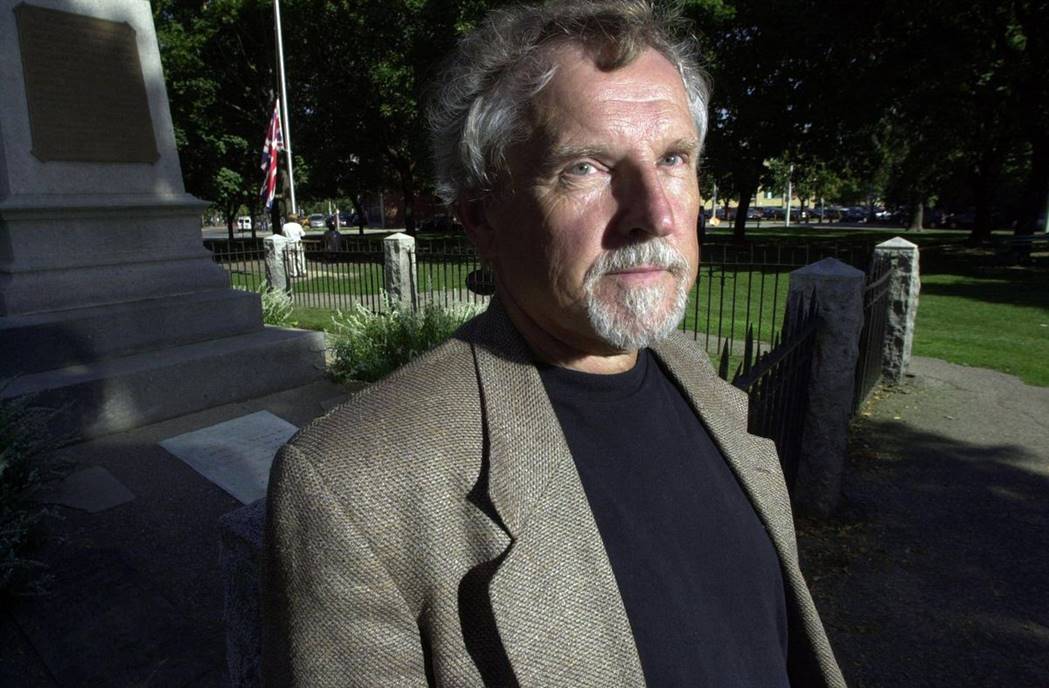

Richard B. Wright (1937–2017) Richard B. Wright (1937–2017) LONDON, ONTARIO – Back in the summer of 2015, I was editing The London Yodeller, then in its prime, and had the opportunity – and the space – to properly discharge a debt of gratitude to the Canadian author who had influenced me more than any other. It had been a half decade since Richard B. Wright had published anything at that point and I sensed things were winding down and wanted to pay tribute before it was too late. Here is that five year old feature. IN 1970 AT THE AGE of eighteen, I happened upon an American edition of Richard B. Wright’s very first novel, The Weekend Man, remaindered for 99 cents at Coles, and read it in one delirious go, thus commencing my four and a half decades-long campaign to spread the good word on my favourite Canadian writer. Fifteen years my elder, Wright’s novelistic career was getting underway at the same moment as I was just beginning to see myself as a writer. Our styles, backgrounds, preoccupations and ambitions hardly overlapped which was perhaps a blessing as I otherwise might have, consciously or otherwise, imitated him. Instead I have regarded him all these years as a sort of elder brother in the trade; a writer whose work I love and esteem and whose progress I have tracked with fraternal interest as he has turned out twelve superb novels; always wishing the world would do a better job of valuing him at his worth. Wright’s greatest strength has always been the uncanny verisimilitude of his storytelling – both the all too credible incidents he writes about and the flawlessly natural prose in which his tales are rendered. Wright’s is an unflashy gift too readily overlooked in an age when the hyper-poetic prose of a Michael Ondaatje or a Jane Urquhart tends to scoop up all of the prizes. His stories of contemporary Ontario life are routinely populated by likable, thoughtful, middle-aged types who never quite manage to take hold of the steering wheel of their lives; because of a complexity they can’t deny, a decency they won’t discard, a haunted disconnect between a remembered past and a not so luminous present reality or just a wicked sense of humour that can’t be suppressed.  THE WEEKEND MAN (1970) set the Wright template. Thirty year-old textbook salesman Wes Wakeham is estranged from his overbearing wife and feeling markedly ambivalent at the prospect of a reconciliation. While not exactly jubilant with his quasi-single status, he has nonetheless found ways to make life a little more interesting outside of Molly’s too controlling orbit – even if it only means taking a different route to his job each morning depending on which slip of directions he picks out of a repurposed peanut butter jar. A weekend man such as himself he explains, “is a person who has abandoned the present in favour of the past or the future. He is really more interested in what happened to him twenty years ago or in what is going to happen to him next week than he is in what is happening to him today. If the truth were known, nothing much happens to most of us during the course of our daily passage. It has to be said. Unless we are test pilots or movie stars, most of us are likely to wake up tomorrow morning to the same ordinary flatness of our lives. This is not really such a bad thing. It is probably better than fighting off a sabre-tooth tiger at the entrance to the cave. But we weekend men never leave well enough alone. First off we must cast about for a diversion. A diversion is anything that removes us from the ordinary present.” At novel’s end, about to give another chance to a marriage that he suspects is still fundamentally knackered, Wakeham muses: “Molly believes that the only reason I am not successful is because I am willfully opposed to worldly success. In her eyes I am a thwarted idealist who has difficulty coming to terms with life as it is lived in our day and age. This is not so. I am not opposed to worldly success and am no more a thwarted idealist than a pygmy’s uncle. The truth is that I am not a success because I cannot think straight for days on end, bemused as I am by the weird trance of this life and the invisible passage of time.” The prototypical Wright character is hemmed in both by the demands and expectations of others and his or her own over-riding awareness of the implacable inevitability of fate; a bone-deep knowledge that however much they might like to see things turn out this way or that, life probably has other plans. There is a rich understanding of family dynamics in all of his books, an appreciation of how in passing on their gifts and attributes our parents both equip us, and in a way unfit us, to deal with life. This is especially highlighted in the perfectly tuned opening paragraphs of Wright’s eighth novel from 1995, The Age of Longing, the book which I consider to be the best of a very good lot. This scene succinctly sets up the struggle that editor Howard Wheeler will be dealing with all of his life, trying to reconcile the two sides of his biological heritage – the priggish but dependable school teacher mother whose careful, measured approach to all things makes a sustained existence possible yet makes life scarcely worth living – and his impulsive father who recklessly reached for the stars as a hockey player and failed, leaving himself with no plan B for navigating any other kind of existence. “When I was three or four years old, I used to look for the Stanley Cup in my mother’s china cabinet. This search arose from perhaps my earliest memory: my father is holding me under one arm while I grip the basin of a drinking fountain in Little Lake Park. With his free hand, my father presses the lever, and looking down I am both astonished and delighted by the cold water gushing from the white mica ball. Around me are the cries and laughter of the bathers and my mother’s voice, insistent and hectoring, the voice of the schoolteacher who is used to issuing instruction or admonition. “‘Be careful, Ross! Don’t let his mouth touch that!’ “For my mother, polio germs lurked everywhere, but especially in places touched by the lips of strangers. Drinking thirstily, I hear too the voices of children nearby. “‘That’s Buddy Wheeler. He played for Montreal and he won the Stanley Cup.’ “They are talking about the man who is holding me, my father. And where then was this cup he had won? Why was it not with the other cups in the kitchen cupboard or the china cabinet? Of course, those children got it slightly wrong as most of us do when we hear stories. My father did play four games in the National Hockey League with Montreal. But it was the year after they won the Stanley Cup. And I am referring to a team that is now only a glimmering memory for a few old people. They were called the Maroons.” (One wonders if Wright, like me, ever used to hear the word ‘maroon’ used as a term of abuse; when you were tired of calling someone a garden variety ‘moron’ and wanted to renew it with an exotic new lustre?)  WRITERS ARE OFTEN exhorted to write about what they know and, aside from the writing life, the two professional milieus that Wright knew best were teaching and publishing. The main characters in Wright’s books, and the parents of the main characters, are frequently teachers and professors, writers, journalists and editors and folks who work in the publishing trade. Born in Midland, Wright himself worked briefly in Toronto journalism and then spent a decade working for the publishing houses of Macmillan and Oxford University Press. No small part of his appeal for me is his insider’s understanding of the thrill and the frustrations of the writing life. His second novel, 1973’s In The Middle of a Life (which picked up the Faber Fiction Award in Britain) presents a brutally funny portrait of a blocked up writer driving his increasingly sceptical wife around the twist with his capacity to kid himself that he’s making real progress on a book that has spiraled completely out of his control. Again from The Age of Longing, here Wright gives us the editor’s perspective on a writer who just doesn’t have it anymore. Howard Wheeler, is now an aging, old school editor impervious to new trends who’s being squeezed out of his job by the arrogant new brooms who’ve taken over the firm. Recovering from a heart attack while back in his old home town settling the estate of his recently deceased mother, Wheeler has been given the job of vetting an immense and turgid dud of a manuscript submitted by Charles Pettinger, a once popular and innovative writer who’s disappeared so far up his own ass that the firm wants nothing more to do with him. “Pettinger’s novel is a shattering disappointment. I read until two o’clock this morning, heartsick at the lifelessness of it all. It saddens me beyond telling to report that his new book is a turbid sermon on the collapse of hope in our century. The vitality and wit so evident in his two earlier books have vanished, replaced by humourless rhetoric and dire warnings about the evils of technology. His characters cannot open their mouths without delivering major statements. The book has no narrative energy; only a bleak message that translates roughly into ‘I told you so.’ And the confounded man has been working on this for nearly twenty years! Think of it if you can bear to! Twenty years! Now he sits in his farmhouse awaiting news from the publisher. Trembling with excitement. Sick with nerves and anticipation. Dying for that treble scotch which he has forsworn these past several years on medical advice. Can anyone with a heart not wish the man well?” The only near-constant element in Wright’s novels that doesn’t seem to be drawn from his real life are the marriages. Wright’s fictional marriages are nearly always in crisis while, to all appearances, his own has held up commendably from the day he married Phyllis Cotton in 1966. They have two adult sons and 2010’s Mr. Shakespeare’s Bastard, the most recent of his twelve novels, is dedicated to Phyllis and “our newest grandson, Nathan”. One possible reason for the success of his marriage is that, unlike a lot of his authorial characters, the ever-sensible Wright realized and accepted that he would not be able to make his way on the avails of novel writing alone – though there was a period of five or so years when he gave that his best shot and the collapse of that scheme must have necessitated a sobering, if not discouraging, readjustment. Wright stopped working in publishing in 1970 and attended Trent University, earning his B.A. in English two years later, thereby equipping himself to take on a full time position teaching English at Ridley College. Except for his half-decade escape in the early ‘80s, this was a position he held until his retirement. Established in 1889, Ridley is a private Anglican boarding school, a university prep school, situated on 108 acres of parkland and includes among its roll of notable alumni, London’s Hume Cronyn. Girls – a small sampling of 11 at first, just to see if they worked out - were finally admitted to Ridley in 1973, right around the time that Wright first turned up there to teach. A dependable day job not only spares a writer the wild vicissitudes which invariably trouble those who depend on art to sustain them, it also – and I expect this was crucially important to Wright’s independent temperament – leaves him free to follow his own instincts and preferences without having to re-jig those instincts so that they align with the current literary zeitgeist in whatever form it happens to take that week. Of course many writers with demanding (or even not so demanding) day jobs have had their literary ambitions frustrated, dissipated and then abandoned when they have to parcel out their attention and their energy in such a bifurcated way. But the very disciplined Wright made it his routine to rise as early as five a.m. to give the best and sharpest part of his day to writing before going off to commence a full day’s teaching at Ridley. The Weekend Man and In The Middle of a Life – a more mature and grounded and wonderfully funny novel whose main character named Fred Landon (also the name of a Forest City teacher and historian who loaned his name to our Wortley Road Library) always makes Londoners do a double take – were products of Wright’s years in the publishing biz.  THEN CAME FARTHINGS' FORTUNES from his first run at Ridley, the longest and least typical book of Wright’s entire career; a sprawling picaresque romp that follows an itinerant roustabout who traverses the globe in search of lost love and fortune and like some ancient precursor to Forrest Gump or Woody Allen’s Zelig, has a knack for turning up in far flung locales at historically significant moments. I remember enjoying it very much when it was first published but it’s not a book I’m ever tempted to return to. The inventiveness and the drive are undeniable but the story feels a little donnish (“See how much I know about history?”) and too consciously manipulated. And, I’m sorry to say, I feel much the same about his much slighter effort of 2010; a speculative imagining of the Bard’s early life, Mr. Shakespeare’s Bastard that also feels as if its content has been cribbed rather than lived. The effortlessness and naturalness I value in a novel by Wright don't flow so readily when he steps too far outside of his own time and place. These invigorating qualities were highlighted by The New York Times reviewer of his very first novel when he wrote: “Mr. Wright writes with the apparent ease of breathing, and he is both touching and very, very funny because you do not catch him trying.”  THE FIRST FRUIT OF Wright’s independence was 1980’s Final Things, by far the most violent book in the Wright canon. Taking his inspiration (if that’s the right word) from the horrific molestation and murder of a Toronto shoeshine boy caught up in a pedophile ring, the novel’s 150 very tightly printed pages constitute a nightmarish descent into a sordid world where, for infantile considerations of profit, children – to an extent – offer themselves up to be exploited by immoral monsters. The boy’s parents are already divorcing when the unthinkable happens and projections of the guilt that each of them feel for letting their only child slip out of their care are added to the usual recriminations of any disintegrating couple. Next up was 1982’s The Teacher’s Daughter. Crime is an element in this novel too – a badly botched bank heist – but the real focus is an ardently desired but wildly unsuitable and ultimately impossible love affair between two lonely people who cannot shake off the conditioning and assumptions of their widely disparate backgrounds to create any ground of common understanding where they will be able to live together.  WE MAY LIKE TO believe that here in the new world, citizens are not sequestered by impregnable class divisions but The Teacher’s Daughter makes a very strong case that although our signifiers of distinction might be different than those that pertain elsewhere, we too are class-riddled. The longest gap ever between Wright novels was the six years between 1984’s Tourists (the last book of his occupational independence) and 1990’s Sunset Manor (the first book after his return to Ridley). I’m just speculating here but can’t help wondering if Wright, foreseeing and dreading the possibility of such a return, wasn’t engaging in a little pre-emptive bridge-burning in writing Tourists which gleefully mocks the antiquarian ethos of schools like Ridley via its narrator, Philip Bannister; an officious snob of an English master at an exclusive boy’s prep school who murders his unfaithful wife and a hideous American couple she’s fallen in with (deliciously named Ted and Corky Hacker) while on vacation in Mexico.  TOURISTS IS THE wildest, broadest comedy Wright has so far written with Bannister delivering exquisitely rendered bon mots of breathtaking bigotry: “I had remarked to my wife that the stolid brown little women in their long dresses and shawls looked as durable as large chess pieces. I imagined that people with such a low centre of gravity would be very difficult to tip over in a scrap.” In the right hands (like an updated Ealing Studios) Tourists would make a fabulously funny movie but the uniformly uncomprehending and disapproving reviews in the papers that I saw – like some dreadful advance guard of the PC police at their most humourless and obtuse – gormlessly wondered if this was really the sort of book that an author who wanted to be taken seriously should be writing.  PERHAPS THE MOST serene of all Richard Wright’s novels is Sunset Manor. There are no collapsing marriages or serious crimes to drive along this gently comedic and often touching study of a retired, spinster teacher of English who (shamed and alarmed by a kitchen fire caused by her careless smoking) comes to recognize that it is time to place herself in the care of a retirement facility. We get to know a fairly large cast of characters and marvel at how the old fires of vanity, appetite and pride still burn away in the hearts of Miss Ormsby and her fellow residents. The primary struggle of the book is between Miss Ormsby and the facility’s administrators and medical staff. Having devoted her life and career to artful and truthful expression, she is not about to chuck that now and submit to all their evasive happy talk about what lies ahead for the residents. Not only does she refuse to heed her doctor’s advice to “forget all this nonsense about death”; she knows that “only by thinking of death can one come to value and enjoy life.”  YOU KNOW MY high regard for 1995’s The Age of Longing. If you’ve only got time to read one of his books, make it this one. It wasn’t reviewed widely, didn’t sell fabulously but did pick up a couple nominations for Canadian literary prizes. Then Wright’s ship of good fortune finally came through in 2001 for his ninth novel, Clara Callan. After decades of critical neglect, so-so commercial sales, and nary a sniff from movie producers, this quietly stubborn and utterly original writer suddenly won every Canadian literary prize worth having – the Governor General’s, the Giller and the Trillium. Those of us who had been flagging Wright’s greatness for decades couldn’t help wondering – why now? Why this book in particular?  THIS TALE OF TWO sisters from small town Ontario who struggle to make their very different ways through early adulthood in the 1930s – one as a teacher in the school where her recently deceased father was principal, the other as an actress in American radio soap operas – was celebrated for its insights into its female characters and the evocation of their voices, all conveyed by their letters and journals. But Wright had done that before; one of his more sustained explorations of the female psyche being Sunset Manor’s Kaye Ormsby. Also commended was his grasp and easy integration of early 20th century details and atmospheres but again, all that was beautifully handled in The Age of Longing.  I WAS SO MYSTIFIED by Clara Callan’s success, I think I downplayed its value – rather like a teenager who gets petulant when some obscure band he’s loved for years suddenly lands a number one hit and is taken up by everyone. I revisited it over Christmas this year and was won over anew by its power and beauty. It is indeed one of his very best books. Those prizes were no fluke. In the wake of this orgy of long overdue awards, Wright’s by then extensive back catalogue was all reprinted and while his readership was enlarged, sales were not phenomenal. He has not entered that pantheon of household name status where writers such as Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro imperturbably reside. Three years later when his next novel, Adultery, was published, his publishers expected a much larger audience which wasn’t there. I was heartsick when CBC’s The National ran a story about trouble in the publishing/bookselling industry, showing huge stacks of Adultery heading into the pulper. It just hadn’t moved like everybody thought it would and nor has anything else in the Wrightian canon.  A GRIPPING EXAMINATION of the appalling fallout of a meaningless fling, I remember walking into town on an errand of some kind during my first read-through of Adultery and being so relieved to realize that this all-encompassing gloom and anguish I was feeling was all because of the brilliantly effective book I was currently reading; that I personally was off the hook and life was good. It is the most claustrophobically menacing book that Wright has written since Final Things. The last novel that I will comment on here is the aptly titled October from 2007; Wright’s most sustained meditation on death. It tells the story of retired professor, James Hillyer, who is reeling with the fatal diagnosis of a beloved daughter (who is dying of the same illness that carried off his wife) when a wealthy, manipulative, and now painfully afflicted friend from his youth for whom he’s always had ambivalent feelings requests that Hillyer accompany him to a special Swiss clinic where he intends to terminate his suffering life. Weaving reflections of his own complicated coming-of-age with all these present day intimations of mortality, it is often the dying themselves who provide Hillyer with the perspective to accept things as they apparently have to be. Even the grimmest of Wright’s tales are never without moments of humour and grace and October is no exception.  IN HIS WONDERFULLY insightful entry on Wright in The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature (1997), the late Tom Tauskey of Western quoted from Wright’s then most recent novel, The Age of Longing, to say that a common quality with many of Wright’s main characters (no heroes here) was their propensity for getting “psychologically cornered by the prospect of finitude.” Let me quote the original passage where Tausky found that quote. This is Howard Wheeler again from The Age of Longing talking about Charles Pettinger’s writing before he lost his gift: “The stories are both funny and serious and they represent a genuine attempt to understand the difficulties of living in a post-Christian world in the last quarter of the century. The characters in these stories are not only baffled by the moral emptiness of materialism but also psychologically cornered by the prospect of finitude. Yet they somehow endure. Pettinger has been labelled with some justification as Canada’s Walker Percy, though, of course, Pettinger hasn’t been nearly as prolific as the late Southern novelist.” Picking up on a reference dropped in an interview from early in the career of the media-averse Wright in which he said that he had been influenced in his writing by Walker Percy’s first novel, The Moviegoer, Tauskey makes it clear that in this passage in which one of Wright’s characters writes about the writing of another of his characters, Wright is in fact telling us something about how he sees his own mission as a writer. (And in the explosive moral rage that concludes 1980’s Final Things I’ve long wondered if Wright hadn’t been influenced by Percy’s Lancelot.) Percy – a loner, an outsider, a fearlessly funny philosophical existentialist as surely as Wright – was in the process of converting to Roman Catholicism while writing The Moviegoer and the faith informed his many subsequent novels. Faith didn’t make everything better for Percy but it did provide him with armour for the fight. Wright has never had this and still has soldiered on, creating a body of work that I consider more courageously insightful than that of any other Canadian novelist.  THERE'S AN ACCOUNT of a televised Christmas Eve mass in The Weekend Man that is pretty scathing and in The Age of Longing there’s a pompous clergyman who gets up Howard Wheeler’s nose by pretending to have known his mother much better than he did. But more often than not, particularly in his later writing, Wright references Christianity wistfully, seeing its beauty and the order and steady reassurance it provides to those who can tap into it. I’ve had the privilege to introduce Wright at about a half dozen London readings over the years and to go out with him afterwards for food and drink. (Always a gracious guest, I couldn’t help wondering if Wright’s spirits never sank upon sighting me on yet another London podium: “Oh God, Goodden again. Does nobody else in this blighted burg read me?”) In the wake of his Clara Callan reading, I asked him if any of the phenomenal media coverage of this book had surprised him. Yes, he told me. About 20, 30 pages in, Clara loses her faith and it’s a pretty big deal in her life, signalling a major shift in her perspective and attitude, and this went utterly unnoted in every review he’d seen of the novel. It shocked him. “No one understood its importance for her,” he said. “They didn’t think it was worth mentioning.” I opened with a reference to my four and a half decades-long campaign to win readers over to my favourite Canadian writer. I’ve had a fair bit of success with this (particularly with men) but when I’ve failed, the most commonly heard objection to his writing is, “I’m sorry – I just find it too depressing.” There are writers out there I understand to be first-rate but who I avoid for that same reason, such as John Updike (just his novels; I adore his critical writing) and Philip Roth (whose characters strike me as needlessly ornery and perverse). Obviously, I don’t have that problem with Wright. I know his subject matter is frequently grim but his treatments never strike me as gratuitous, his main characters always have a streak of decency running through them, and damn it, the subjects he probes and the questions he raises are important. And again and again he delights me with the humour he finds in the most unlikely places and he thrills me with how naturally and perfectly he manages to pin down every detail and nuance of our messy and complicated lives.  SO THAT WAS THAT, I thought. Homage paid, career nicely summarized, a debt discharged. And then two and a half months later, I’ll be damned if Wright didn’t go and produce a totally atypical and utterly unanticipated memoir. Ever the completist, I couldn’t leave that flapping in the breeze and unaccounted for. So I made him the subject of The Yodeller Interview for our October 22, 2015 issue. Here is our final exchange of words from an interview conducted about fifteen months before his death: ABOUT TWO MONTHS after publishing my ‘summer reading feature’ on the novels of Richard B. Wright, Simon & Schuster published my favourite Canadian writer’s memoirs, A Life with Words. Though its cover is execrable (the publisher’s call not his; and in the interview below Wright has a few things to say about the current state of publishing) the book itself is a wonderfully funny and touching look back over his life and career. Having hosted Wright on the London stop of numerous book tours, I had a St. Catharines phone number in an old address book dating from the 1980s and acting on my hunch that such an innovation-averse chap was unlikely to have upgraded to a cell, I gave that old number a dial and voila - there he was. Then, knowing he had a new book to promote, I really pushed my luck by asking if the media-shy Wright would consent to an interview. And reader – he said, ‘yes’! What motivated you to write a memoir at this time? I wanted to look back on my life and see what I had done and what I had not done. I thought this would be an opportunity to do that, particularly if I chose to use the third person because I could then distance myself from myself. And it seemed to work. As I went along with it, it was more like writing a novel than an actual memoir. And I avoided that ‘I did this’ and ‘I did that’ stuff that so irritates me but you can’t get around it if you use the first person. So by using the third person I’m able to look at myself like a character in a novel and that really helped. I can think of instances when authors have used the third person in a memoir – Russell Kirk, for one – and they actually come off sounding more pompous than if they’d gone with the first. Well, they do. And I think Salman Rushdie is a good example. Now I haven’t read it but it was referenced a couple of times by reviewers of my book where they said, ‘Wright is completely different from this. He seems to be almost modest about his accomplishments and that’s why he didn’t want to use ‘I’.’ But I can see how it could get very heavy on the self-importance thing depending on how you did it. Your use of the third person did not carry that effect at all. I stopped noticing after half a page and found the writing as direct and compelling as yours always is. Of course when someone publishes a memoir, readers can’t help but wonder, are we wrapping things up here? Is he getting ready to close up shop? Well, that’s part of it too, I think. I wanted to see my life, if I could portray it in an honest way, and then you look around and ask, ‘Well, what’s next?’ The memoir isn’t quite my last book because I’ve finished a novel which will be published next spring. Can you tell us anything about it? It’s called Nightfall and that reference comes from a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins. You probably remember October? It’s based on some of the characters from October – at least two of them – James Hillyer who was down to Gaspe when he was a boy of 14 and the girl Odette Huard, a French Canadian girl who was after the wealthy American boy who had become crippled through paralysis. They interested me and I wanted to look at those characters again as adults and so I framed the book that way. James has lost his daughter and his wife to cancer and has a hard time getting over it. He thinks he might be able to get some sleep if he can focus again on those happy days in Gaspe when that lovely girl was there, even though he lost her to Gabriel. This is what he does and he eventually looks for her. He looks her up with the help of a couple of people and finds that she’s still alive and living in Quebec City and decides to go and meet her and see what she’s doing. She’s had a very interesting life. She’s had a lot of trouble with men – and in particular one man who’s been in and out of jail a lot, a really rough character – now in his 80s, who’s got Alzheimer’s. All of that is explored and it all takes place in Quebec City. I enjoyed exploring all that. Quebec City is my favourite place in Canada, really. It was our honeymoon capital. Then you chose a good one. My wife Phyllis and I have been there many times. So we went and I just could see where Odette would be and positioning her with this shy university professor. The two of them get together and it’s a look at ageing love and what you do when you find love again in your 70s. That’s Nightfall and that’ll be out in the end of April. So that’s my last novel, I think, but I’m not going to promise anything.  You are lately featuring these elegiac titles . . . October . . . Nightfall . . . Oh, absolutely. You do that. I’ll be 79 in another few months. I’m an old man now. There’s no question about it. I’m old and I don’t mind being old. I’m lucky I made it this far. Did growing up in Midland help you develop as a writer? Alternately did it present any obstacles? Anybody with ambition wants to get out of a town like Midland. If you said you wanted to be a writer, you were being presumptuous. A town like that kind of crushes you. Alice Munro has written about this. Who Do You Think You Are? is a perfectly titled book for people growing up with artistic ambitions in a small town. The town of Midland wasn’t particularly friendly to a writer because they just would have thought such ambitions were outlandish. Can a case be made that growing up on the periphery like that leaves you free to cultivate your own sense of things? Absolutely. That’s the good part of it. You just say, ‘Okay, “I’m going to do this my own way. I’m not going to get any help from the people around here.’ Not that writers necessarily need help but sometimes a little encouragement might help. But I didn’t get any of that and I didn’t expect to get any of that and you get used to that. I was gobsmacked to read in your memoir that you suspect your mother likely never read any of your novels all the way through. Oh, I’m sure that’s true. She wasn’t a literary person. She didn’t read much and didn’t read stories to me. She’d memorized fairy tales. She was a very interesting woman and I loved her deeply but she wasn’t literary. The world I was exploring was completely alien to her. Now we know your father at least read the Somme section of Farthing’s Fortunes because it jogged him to finally tell you something about his war experiences. Generally, were your father and your siblings a little more supportive, or, at least, interested in what you were up to? No. My father was sort of puzzled by me, I think. But he loved me and that was it. I told him at one point, ‘I’m a bit odd,’ and he said, ‘I suppose so but it doesn’t matter.’ My brothers were just older brothers. I was always the brat. It’s interesting, one of my brothers phoned me the other day and he had his whole family there. And I was thinking they might not like this book because they don’t get much mention but he loved it. He said it was a wonderful book and he had all of his kids speak to me on the phone. I was quite touched by that. I didn’t expect it. And I’ve had a similar experience with one of my other brothers. One of my brothers unfortunately is slipping into dementia and doesn’t have the capacity to enjoy it. I have a sister who is also suffering from dementia. They’re all older than I am and they’re all in their 80s. There’s that one lovely family photograph in the book from Christmas of 1953 – what a stunningly handsome crew. We were rather good looking when you look back on it. All my sister cared about was looking pretty and my brothers all had money because they worked on the boats and would come home in the fall and buy clothes. I think perhaps my favourite sequence in the whole book is the very liquid supper with adman Harry Painter who helps you realize that your three years’ investment in an education in radio and TV arts has been a total waste of time; that if you want to see your talent survive you must seek employment elsewhere. I know fiction writers hate to be asked, “Did that really happen?” But surely memoir writers can’t object. That’s a true tale. He wasn’t named that, of course. I didn’t know where to go or what I should do. It’s so different from today when if you think you want to write, then you’ll join a group or take a class. There was none of that. I love it when writers make mention of the books that really impacted and influenced them. One of yours that was huge for me as well and which no one else seems to talk about anymore is Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. Oh yeh, a wonderful book. It reminded me a lot of my town and the people in it and oddly enough, when I went to Macmillan’s to work, the president of the company, John Gray, one time we were having a lunch at the Silver Rail and he said that when he was a kid he wanted to be a writer too and that was the book that really inspired him. But then he didn’t carry through with it and became very successful in publishing. He was very impressed that I’d read Winesburg, Ohio because even then, it was seen as out of date. Writing about your years as a publisher’s reader and sales rep as well as your career as a novelist, A Life with Words presents a history of Canadian publishing through the last third of the 20th century and up to the present day. And it’s interesting to see how you never really were part of the presiding zeitgeist. I was clearly unimpressed by that very Canadian movement in the early 70s when I had my enemies. David Godfrey was my spectacular enemy. Do you remember him? I remember the name. Things Go Better with Coca Cola? Is that him? No, he was a big shot in pro-Canadian publishing [and one of the co-founders of House of Anansi]. And then he went off and wrote a book after a year in Africa [The New Ancestors]. He was my enemy and didn’t like my work at all and went out of his way to say so - in a very uncivil manner. I nearly punched him out once . . . should have now, when I think of it. He was part of it, and Margaret Atwood and these other people talking about ‘victimization’. I had no time for that. I was an outlier and was happy enough being out on the fringe of it. I wanted no part of the Toronto-centric writers’ scene and just ignored them and got on with my life. This Godfrey book I’m thinking of was some kind of anti-American screed and the title, now that I think of it, was Death Goes Better with Coca Cola. Yes, you’re absolutely right. Good for you. I’d forgotten that. That’s the same guy, yeh. He was a pill. A pain in the ass. We hear so much about the collapse of publishing culture in the present day but some of the stuff you went through in the supposed heyday of Canadian publishing makes me wonder; has there ever been a golden period? Well, speaking from personal experience I would say maybe the 70s and the 80s up until the collapse of it all with the internet. When we get into the 21st century and the internet is making such an impact on everything . . . and the word ‘blog’ had been invented . . . that to me is the ugliest word in the English language . . . I just know as I talk to publishers now, how desperate they are. They can’t send people out the way they used to. I used to go on tours right across the country but they can’t afford it now because the overheads are there and they’re not getting the same sales they used to get. We’re still in business, thank goodness. But there are a lot of publishers now who are just goofy publishers with goofy names like Book Thug and people like that. Thirty year-old teenagers I call these people. I knew your career had gone through fluctuations but reading A Life with Words - an author with four books under his belt, glowing reviews and the odd award and then you get that kiss off letter in 1980 from Macmillan’s new vice president who doesn’t seem to know that his firm is bringing out your fifth book in just a few more weeks . . . And then you have that low ebb where you get a royalty cheque for $2.85 . . . I’ve got that on my office wall to remind me of hard days. And you go, ‘My God, this man’s had rave reviews in The New York Times and The London Times, he picked up a Faber Fiction Award and he’s been published in how many different languages, and you’re treating him like this? Yeh, that’s what happens. You’re only as good as your last bestseller, I guess. But I enjoyed the trip. That’s the point of it all. Though I had some rough times and had to cope with some serious anxiety at times, I’m glad I did it. I set out to do it and I’m glad I got it done and I can take that to my grave anyway. If Clara Callan hadn’t happened the way it did – and some of us believed you deserved that level of popular success all along – but if that book hadn’t taken off like that, how do you think you would look back on it all now? I think I would still have enjoyed the experience. Clara Callan was a pleasant surprise. It’s not my favourite of the books I’ve written. It was a financial success for me more than anything. I got the Giller Prize [and the Governor General’s Award and the Trillium Prize] which was a big help in establishing yourself as a serious writer. But without that, I think I would’ve carried on as I always have. Looking back over them all, is there one book you wish people gave a little more attention or credit to? I wish that the hockey book (The Age of Longing] had a few more readers. It did establish me after a very fallow period. I enjoyed writing that book an awful lot and I would have liked to see it do a little better. Mind you it was on the short list for the Giller Prize and that was really a sort of resurgence, a renaissance for me because I’d been going through a time when I wasn’t getting much attention. The Age of Longing was a book that made me want to go on writing at a time when I wasn’t sure and the red dog [of anxiety] was really barking at me. That gets me to the end of my prepared questions. Is there anything else you’d like me to throw a little spotlight on? No, I don’t think so. I want just to thank you for saying such good things about my work over the years. You’ve been a very loyal supporter of my work . . . (laughs) you and two or three other people. Surely you have at least one person like me in most towns? Well, I wouldn’t say in most towns, no. A little bit more now perhaps than when you and I were in London in those old days which I still remember with a great deal of pleasure. Those were swell events. We’d get Chris Squire to cook us up a dinner and then knock back the scotch until three a.m. and talk about books until the cows came home or we all passed out. Exactly. It was a terrific time. You can’t do that so much now. They won’t even send me to London. It’s great to hear from you again and hear that you’re still in business there with your Yodelling. And I’m delighted to hear we’ll be getting another novel from you in the spring. Yeh, we’ll see what happens. At my age I’m not going to worry too much about that.  THE TIMES ARE NIGHTFALL Gerard Manley Hopkins The times are nightfall, look, their light grows less; The times are winter, watch, a world undone: They waste, they wither worse; they as they run Or bring more or more blazon man’s distress. And I not help. Nor word now of success: All is from wreck, here, there, to rescue one – Work which to see scarce so much as begun Makes welcome death, does dear forgetfulness. Or what is else? There is your world within. There rid the dragons, root out there the sin. Your will is law in that small commonweal.

1 Comment

SUE CASSAN

20/7/2020 07:00:52 am

What a wonderful reminder of a great and enduring Canadian writer. He has a body of work that stands the test of time. There have been a few novels that I missed. I’m going to repair those omissions . Thanks for sending up the flag again, and for sharing the treasure that is Penelope Fitzgerald .

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed