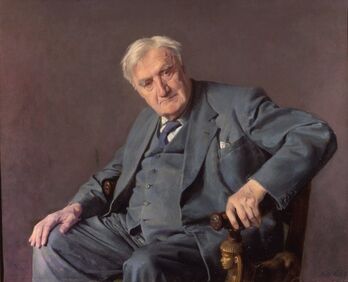

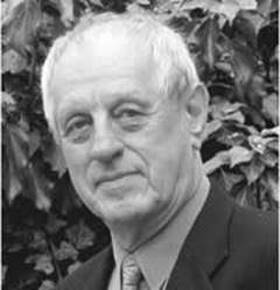

Ralph Vaughan Williams Ralph Vaughan Williams LONDON, ONTARIO – As these dispiriting state-imposed sanctions to squelch the spread of the Chinese Batflu drag on, I’m all a-twitch this Advent season with withdrawal symptoms brought on by the unholy ban on choral concerts and singing in our churches (which are only allowed to operate at thirty per cent capacity anyway). A life without the regularly applied ministrations of choirs and congregational singing – aural bombardments which can be as soothing and stirring as a deep spiritual massage – is a real impoverishment at any time of year. But that deprivation feels particularly acute over Christmastide when so much of the music that I have loved best – carols and hymns with nourishing roots that go tendriling all the way back to my infancy – is sealed away under a quarantine that one might call whimsical if it didn’t feel so sadistic. Throughout this enforced famine on live and participatory music-making which has now been in place for ten long months, my CD player has been even more frequently employed than usual. In particularly heavy rotation in these last few weeks of divine anticipation has been the wealth of Christmas music produced by the great English composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958). It was Vaughan Williams’ immense and utterly beguiling body of original compositions – as well as his arrangements of traditional folk-songs and carols which in turn informed virtually everything he wrote - that served as my way in to an appreciation of classical music generally. Late in his life, Vaughan Williams whipped off a wonderfully down-to-earth essay about his own education and development which was originally included in Hubert Foss’ 1950 study of his music. A recurring motif in this essay is the inspiration which the composer drew throughout his life from older traditional songs: “I must have made my first contact with English folk-songs when I was a boy in the ‘eighties, through Stainer and Bramley’s Christmas Carols, New and Old. I remember clearly my reaction to the tune of the ‘Cherry-Tree Carol,’ which was more than simple admiration for a fine tune, though I did not naturally realize the implications involved in that sense of intimacy. The sense came upon me more strongly in 1893 when I first discovered ‘Dives and Lazarus’ in English County Songs. I had that sense of recognition – ‘here’s something which I have known all my life – only I did not know it’.” And just as fecund a source of inspiration for him were the common hymns of the Christian church. Indeed Vaughan Williams went on to edit two large collections of hymns ancient and modern (The English Hymnal and Songs of Praise) and The Oxford Book of Carols. Recalling the misgivings which assailed him when he began work on that first hymn collection in 1904, he wrote, “This meant two years with no ‘original’ work except a few hymn-tunes. I wondered then if I was ‘wasting my time’. The years were passing and I was adding nothing to the sum of musical invention. But I know now that two years of close association with some of the best (as well as some of the worst) tunes in the world was a better musical education than any amount of sonatas and fugues.” While he credits the many teachers (including older composers like Parry and Stanford) who manfully struggled to impart what they knew to this most stubbornly unbiddable of students, Vaughan Williams ruefully admits that they mostly struggled in vain. “I have learnt almost entirely what I have learnt by trying it on the dog,” he wrote. The dog he most frequently tried things out on was his good friend and fellow composer, Gustav Holst (1874-1934). This pair who had attended classes in composition together and took part in expeditions around the turn of the century going into the countryside to collect regional folk-songs from old farmers, got together several times a year for what they called ‘Field Days’ when they would settle into a room with a piano to examine and critique and suggest strategies for improving the latest works they were developing. “These orgies must have started early,” Vaughan Williams wrote, “and they continued to the end – that is to say, for nearly forty years. I think he showed all he wrote to me, and I nearly all I wrote to him. I say ‘nearly all’ advisedly, because sometimes I could not face the absolute integrity of his vision, and I hid some of my worst crimes from him. I regret now that I did not face even his disapproval. Without him to criticize me I sometimes feel lost.” In addition to writing nine symphonies, a dozen concertos (a few of which were showcases for such under-featured instruments as the oboe, the viola, the tuba and the harmonica) four operas, several movie soundtracks and hundreds of smaller scale works, Vaughan Williams wrote and/or arranged numerous hymns, oratorios, cantatas, and a mass. All tallied up, at least a third of his total output was music specifically designed to be sung in church. Yet all of his life, when asked, Vaughan Williams always classified himself as a Christian agnostic. He wasn’t being tricky or coy or trying to butter his bread on both sides. This was a precise description of his metaphysical convictions. He could not in all honesty join any Christian sect. But he would not withhold his regard for the Church because of that inability. He knew that Christian stories and music had informed and inspired his imagination. Judeo-Christian ethics were the basis for his society’s laws and the Christian calendar imbued each passing day and season with rich significance. Even if he couldn’t give his full intellectual assent to the faith, Vaughan Williams knew that in a thousand other involuntary ways, his life had been shaped and enriched by the Church. There’s a wonderful story of the composer, early in his career, storming late into St. Barnabas Church in Lambeth where he was the organist and music director. The choir and players were already assembled and waiting to be run through their paces in rehearsing a Bach cantata. Irritated with himself for his uncharacteristic tardiness, Vaughan Williams muttered in a flustered voice that everybody could hear, “And who still believes in Jesus Christ nowadays, I should like to know?” That little outburst of petulance out of the way, not ten minutes later he was slaving to help his singers wring every nuance out of Christ’s words as set by his idol, J.S. Bach. One of his biographers, musicologist Michael Kennedy, astutely identifies Vaughan Williams as “that extremely English product – the natural nonconformist with a conservative regard for the best tradition. In the music of the Church he recognized the only continuous musical tradition in English life. When he was at Cambridge he would go to Ely Cathedral in time for the morning service and sit at the back of that beautiful church listening to the chants echoing among the lofty recesses of the roof. The marvelous prose of the Authorized Version, the fundamental simplicities of The Pilgrim’s Progress – these were necessary food for his artistic spirit and he himself responded to their proclamation of the ultimate mysteries as artists have done throughout the ages. There is no lack of sincerity in his religious music, almost all of which is strongly affirmative.” In my earliest months and years of exploration in the wonders of classical music – much of it anchored in my enthusiasm for just about anything Vaughan Williams wrote – I worried, as only a young and uncertain novice can, if my favourite composer was quite respectable. Wasn’t he just a little too accessible? Shouldn’t real classical music be a little more difficult to love? The man who put such neurotic misgivings to rest for me was Bert Van der Hoek who I first met on a brisk Friday night in the early ‘80s - I’m not certain if it was autumn or spring - when I impulsively darted up the stairs to the old Hysen Music shop on Dundas Street, a few doors west of Richmond. I had been trawling through record shops – downtown London still had quite a few in those days – in search of anything at all that would appeal to me but with at least one eye particularly peeled for lesser known works by you know who.  Bert Van Der Hoek Bert Van Der Hoek The Hysen shop’s specialty was sheet music and text books for music students and they also had a small selection of classical records. I’d been up there a couple times before and decided it wasn’t really my kind of shop but in those days I was primarily plugged into popular music. Now that I was specifically searching out the music of Vaughan Williams, I thought Hysen’s might be worth another try. It was only a few minutes before the universal closing hour of nine so I knew I needed to make short business of this visit or risk the wrath of whoever was manning the shop. I innocently asked the lone clerk with the slight Dutch accent whether they had any recordings of music by ‘Ralph’ (pronouncing the ‘l’) Vaughan Williams. Ever the gentleman, Bert didn’t correct my mangling of the first name but quickly made a quiet point of pronouncing it, ‘Raphe’. He didn’t want to scare me off as an uncultured rube (which I was in many ways) because Bert adored Vaughan Williams at least as much as I did and was eager to share what he knew with anyone who was interested. I didn’t get out of there until almost midnight. When nine o’clock came Bert locked the front door and turned out the downstairs light, and then proceeded to play me samples of music on the store’s sound system, discussing the merits of this or that composition and making references to at least a dozen other composers, contemporary and historical, who had contributed to the great English choral tradition of which Vaughan Williams was such a champion. And out of that first meeting, a fast friendship grew and I soon came to learn that Bert wasn’t just a connoisseur of all kinds of choral music, he was also a practitioner; a composer in his own right and an organist and choir director at a south London church. In early 2005, Bert had retired from Hysen’s and his music director gig and I did up a profile of him for the old Christian Life in London quarterly. I include it here because I’ve always associated Bert with Vaughan Williams and consider him a fine exemplar of our favourite composer’s insistence on regarding music – in its inspiration and its playing – as a part of everyday life. This is an ideal, it seems to me, which needs particular reinforcement today. "HE'S A DUTCHMAN WHO'S gone totally English,” is how Trudy – Bert Van der Hoek’s wife of fifty-three years – sums it up today. She’s a fine one to talk. Every bit as Dutch as Bert (they both immigrated to Southern Ontario with their families in the early ‘50s) she’s got the English choral bug just as bad as him and is happy on their many trips over to England to spend their holidays flitting from choral service to choral service, sometimes cramming in as many as three in one day. During the war years in The Hague Bert used to sit in with the organist at his family’s church and though he had no diploma or degree in music, he was able to pick up work as an organist at churches in Ingersoll and Chatham once he’d arrived in Canada. (He subsequently studied organ and theory in London with T.C. Chattoe, William Wickett and Barrie Cabena and became an associate with the Royal Canadian College of Organists.) “The first time I had a choir in Ingersoll, I had no choir experience,” Bert recalls. “And I looked through the music and we had two anthems to practice and it took us two hours. And afterwards one of the people came up to me and said, ‘Bert, we enjoyed what you’re doing but we usually sing more than two pieces in two hours.’” Having met at the young people’s group at the Christian Reformed Church on Talbot Street in 1955, Bert and Trudy were married in 1958 and in 1960 Bert landed the job as organist and choir director at Elmwood Presbyterian Church on Elmwood Ave. west of Wortley Road; a station he held for 46 years while working with five different ministers. “We had stopped by there on a snowy evening and ducked into a service and found it a very inviting, friendly church,” Bert recalls. “We still go to church there every Sunday and sometimes I still play there if they need me.” Most weeks Bert estimates that he’d put in about twenty hours, researching and selecting what to play, rehearsing with the twenty-voice choir and also playing at weddings and funerals and special celebrations where they could tackle larger works like Bach cantatas, a Schubert mass, or a Christmas Eve service in the high Anglican style of King’s College Cambridge. I asked, ‘Did you send in a little treble on their own to start things off with Once in Royal David’s City?’ “Well, we had a treble, but not a very little one.” Looking back over a long career he manifestly loved, Bert recalls, “I’ve played for a lot of baptisms and some of the junior choir members are now parents and I’ve played for their children’s baptisms. I would go by the readings of the Lectionary and the subject of the sermon – and you’d look for hymns that would fit in with that. I still believe in the awe and mystery of worship. The flow of the service has always been my main concern. When people come out of the service and comment on the worship service as a whole, you know you’ve done your job. It’s not just the music or just the sermon.” Bert took two years to decide that it was time to bow out. “It certainly wasn’t that I was tired of it but you want to step down before people say, ‘Is he still there?’” The church threw a huge party when Bert retired and honoured him with the designation as Elmwood Presbyterian’s organist emeritus. He does a fair bit of substituting for vacationing music directors now, and has actually expanded his range as an organist and conductor by playing at Anglican and Catholic services. I recently suspected, quite correctly as it turned out, that Bert was filling in for our usual organist up in the loft at St. Peter's when one of Vaughan Williams' Preludes on Welsh Hymn Tunes was featured at Mass. Retirement from Elmwood Presbyterian and the music shop has freed up time for Bert’s other musical love – composing. Bert estimates that about ten of his works have been published and at least four of them have been recorded by Canadian choirs. He has recently received commissions to write a mass for an Anglican church in Grimsby, an anthem for Oakridge Presbyterian, and last Christmas the Gerald Fagan Singers performed a new carol on the text of O Magnum Mysterium. “That was new for me to write an anthem with a Latin text. The Royal Canadian College of Organists asked me to write an anthem for their last convention which was also performed for the hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the Huron Diocese at the John Labatt Centre so that was a great honour.” But probably his proudest moment as a composer came in the last week of 2002 when the choir of London Ontario’s St. Paul’s Cathedral was chosen to perform the choral Evensong service every evening between Christmas and New Years at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, England. “James Noakes was the organist at St. Paul’s and he called me at the shop to let me know that they wanted to do one of my hymns. Then Trudy and I looked at each other: ‘Shall we go too?’ And we went. It was a thrill. We were sitting together and they announced the anthem, Watt’s Cradle Song by Bert Van der Hoek. To hear it in that building, I was really honoured. That was a wonderful week. My sister flew over from Amsterdam and we spent New Year’s Eve together at the Regency Palace Hotel on Piccadilly Circus.” Is that your greatest hit – your setting of Isaac Watt’s poem? “I think so. It’s still done all the time.” Do you get paid for something like that? “For church services, you don’t get royalties. It has to be recorded or part of a program that’s broadcast. No, you don’t do this for the money. I appreciate it more when people say, ‘We loved your music.’ That’s the biggest reward.”

2 Comments

Max Lucchesi

15/12/2020 10:04:45 am

Excellent piece Herman, but why no mention of his rousing film scores, some of which, like Scott of the Antarctic, and those he scored during the war for the propaganda department of the War Office, The Flemish Farm for example, he later reworked into major works? I will quibble with the description agnostic and describe him as an atheist and humanist.

Reply

Co van der Steen

16/1/2021 11:25:55 am

Nice to read this about our uncle Bert van der Hoek.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

HERMANEUTICS

If you would like to contribute to the ongoing operations of Hermaneutics, there are now a few options available.

ALL LIFE IS A GIFT :

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITION :

Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed