|

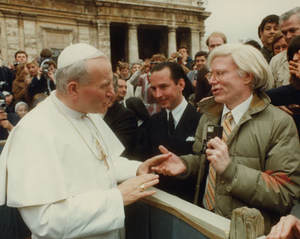

ANDY WARHOL

CATHOLIC AND CONFUSED . . . WHEN I ENTERED the Catholic Church in 1984, my decision to convert was at least partially influenced by the testimony and example of people I admired who happened to be Catholic – particularly writers as temperamentally and politically diverse as John Henry Newman, Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, Ronald Knox, Flannery O’Connor and Dorothy Day. There is, of course, no single Catholic type and this diversity of approaches has always been reflected in the rich multiformity of Catholic worship and devotion. But if it had ever occurred to me to compile a list of people who couldn’t possibly be Catholic, I might well have placed Andy Warhol near the top. So I was intrigued by the newly published memoir, After Andy: Adventures in Warhol Land, by Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni (daughter of English historian Antonia Fraser and granddaughter of Catholic parliamentarian and outspoken social justice advocate Lord Longford) looks back on her life as a society girl, fashion columnist, publicist and gossip-monger with Andy Warhol Enterprises. A lot of her earliest journalism appeared in Warhol’s witlessly prurient, celebrity-sniffing monthly magazine Interview which, incredibly, is still being published today. Fraser-Cavassoni’s book is not a particularly edifying read for anyone of any religious sensitivity or depth. But because of her own familial acquaintance with the faith and the timing of her employment with the world’s first and foremost pop artist (she began her tenure four days before Warhol’s sudden death in 1987 at the age of 58) she is able to cast some light on the fact that astonished much of the world on that February afternoon when his casket was carried down the steps from St. Patrick’s Cathedral in downtown Manhattan: Andy Warhol had been a lifelong, practising Roman Catholic. If I had to identify any single trait that I felt would preclude Catholic affiliation it would have been Warhol’s neurotic aversion to the idea of ‘incarnation’. With his over-riding sense of human detachment that impelled him to call his studio the Factory; with his rejection of traditional notions of craftsmanship in favour of stenciling and screen printing; with his rejection of uniqueness in favour of replication so that one can buy prints of his works but not originals; with his radical devaluation of the genuine and the singular so that even his so-called ‘portraits’ of famous actors and singers are arrayed in rows of near identical images like his famous paintings of soup cans, bottles of Coke and Brillo pads . . . this was a man who never seemed to dig beneath the surface of anything, who insisted on being noticed and recognized but never really known. Never having much use for Warhol, I paid little attention to the accounts of his death and funeral and didn’t find out about his Catholic connection until 1989 when, in an idle moment of morbid curiosity, I leafed through a copy of the just-published Andy Warhol Diaries to see how - or if - he celebrated Christmas. Warhol didn’t exactly write these entries. Mainly as an aid to monitoring his finances he would phone his assistant Pat Hackett every morning and leave an account on her Dictaphone of the previous day’s activities and expenses. She in turn transcribed and edited these daily notes for publication two years after his death. And so for Wednesday, December 25, 1985, he dictated: “Went to 90th and Fifth (cab $4) to meet Paige at the soup kitchen at The Church of the Heavenly Rest . . . Tama had already left because I guess it was too hard. And Paige was upset because she felt the food was so horrible for the people. But it’s just that we’re used to such unusually good stuff. It wasn’t worse than high school cafeteria food. And you see people with bad teeth and everything. And we’re so used to all these beautiful, perfect people. It’s such a different world . . . Passed out Interviews.” At Thanksgiving the next year he’s back manning the church’s soup line and barks at a colleague who’s come along and is being way too bossy with the folks lining up for food: “Victor, we’re here because we want to be.” And then again on the last Christmas day of his life he says: “I got up early and went to Paige’s and she and Stephen Sprouse and I went to the Church of the Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor. There was food for people to take home too and I was giving everybody a lot. If there’s this many hungry people there’s really something wrong.” Certainly, there’s something absurdly comic about Warhol handing out a charity dinner and a copy of Interview to the homeless and indigent. But it’s also wonderfully touching and, more than any art he ever produced, forced me to reconsider Warhol’s humanity and sincerity. In a book tour interview with Rolling Stone this fall Fraser-Cavassoni speculated (much more thoughtfully than she does in her frothy book) on what Warhol valued in the Catholic Church: “Being brought up Catholic gives a sense of hierarchal order, discipline and faith. Faith, when embraced, anchors the creative. I think it would also be fair to say that the romantically rich and multi-layered religion that forgives all – lest we forget! – allows unconventional traditionalists.” Herman Goodden / The Catholic Register / November 12, 2017 |