|

THE CIVIC BLESSING AND INSPIRATION OF TING

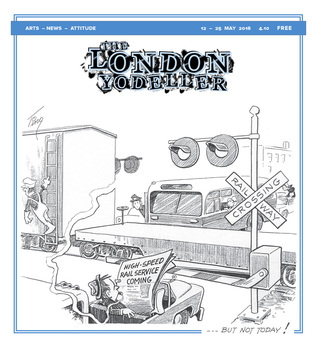

FORTY ONE YEARS AGO next month Merle Tingley (aka Ting), resident cartoonist at The London Free Press from 1947 to 1986, whipped off our cover image for this issue, proving that London’s still unquenched desire for high speed rail service linking us to Toronto and Montreal is at least as longstanding as our similarly fruitless quest for a proper performing arts centre. (Elsewhere in this issue, Barry Wells examines why this high speed dream is likely to remain unanswered for many more years to come.) Our simultaneously nostalgic and prophetic cover image (and several other panels by the now 95 year-old Ting) are featured, along with the work of a dozen other considerably younger artists, at the Third Annual Ting Comic & Graphic Arts Festival on at the Arts Project until May 21. Ting is the perfect namesake for such a festival because (as I discovered when writing extensive biographical sketches of the 18 visual artists involved in 2007’s The River Project) he inspired two or three generations of London artists who pored over his cartoons in the daily paper when they were kids. Whether they aspired to be cartoonists, painters or sculptors scarcely mattered. Here was this very public example of a crackerjack draughtsman with a unique way of looking at things coming up with some sort of pictorial commentary on their world nearly every day of the week. That he ever turned up in London at all was a bit of a fluke as I discovered when interviewing him for Ontario Living magazine in 1988. An out of work veteran who had spent most of the Second World War drawing cartoons for various army publications, Ting drove his motorbike from his hometown of Montreal out to Victoria and most of the way back in his search for a Canadian newspaper in need of a cartoonist. His son Cam told me just last week that, “One night out on the prairies he asked a farmer if he could sleep in his barn and the farmer agreed. So my dad wheeled his motorcycle into the barn and fell asleep on some hay bales, and when he woke up in the morning the cow had completely eaten his handle grips.” In the fall of 1947 Ting pulled into London to try his luck at the Free Press. By then he was so discouraged and broke that he was considering taking on a job selling men’s clothing. “They’d never had a cartoonist of their own,” Ting told me. “They weren’t quite sure what cartoonists did or how they could use one.” He was put to work touching up photographs in a corner of the basement of the old Free Press building on Richmond Street. He accepted the post as his foot in the door but barely a month after his arrival they ran his first cartoon on the front page – a coronation picture of George VIII. The George depicted in this instance was the ever-feisty George Wenige, just elected to his eighth term as Mayor of London. Ting had wormed his way into the job he wanted and was soon cranking out six editorial cartoons a week. “That’s a lot of cartoons over 40 years,” he said, looking slightly incredulous as I performed some elementary mathematics and deduced that he’d produced a minimum of 12,480 panels. “Sometimes I look at old cartoons and I can’t even remember drawing them,” he said. “Or even worse, I’m not quite sure I understand them. They must refer to something that was going on at the time. I can’t think I just made that stuff up off the top of my head.” Ting’s trademark, Luke Worm, was a nameless little squib in a top hat until a Free Press contest in 1951 to name the worm elicited more than 7,000 entries from their readership. The worm itself was born in the late 1930s when Ting, fresh out of high school, landed a job with a Montreal drafting office. “It was an incredibly hot day and I was working away on this cross section of a building and I was just bored silly – all those straight lines and all that precision. Then I got to work on the ground line and that was such a relief because it wasn’t straight. I got a little carried away and drew this worm poking up out of the ground. I got called away on some errand before I had time to erase it. The drawing got blueprinted, worm and all, and I got sacked. My first job and I was out the door but I wasn’t sorry. From that day I’ve put a worm in every drawing.” Ting’s gawky little worm, hidden somewhere in the lines of every picture (decades before Where’s Waldo?), throwing off its symmetry and sabotaging the seriousness of public affairs, was emblematic of Ting himself. “I knew I didn’t belong anyplace that couldn’t make room for that worm.” Other than decades’ worth of cartooning, one of Ting’s more enduring gifts to London was the charitable work he performed for Storybook Gardens which first opened its drawbridge in 1958. Ting offered them his services and ended up designing nearly 50 booths, exhibits and displays – all of it for free. “I haven’t taken a penny for any of the design work. I even handed over the rights to the Storybook colouring book. That’s been my community service.” In the home stretch of our talk, I asked him to reflect on the art of cartooning. He told me that the cartoons that took the most work were almost invariably the weakest; that his best work just happened. One of his most popular was a panel he worked up upon learning that Lester Pearson – the Prime Minister who had overseen the creation of the red and white national flag – had died. “I didn’t even know what I was trying to do,” he recalled. “I drew the peace tower with a flag at half mast, a solid red bar to either side. And right there where the maple leaf ought to go . . . put a bow tie instead. That one just fell into my lap. “There are so many artists I admire, who can draw circles around me, but they can’t do what I do. I’ve held down this job for 40 years and I’ve always been afraid that someone better is going to come along and I’ll be buried in the art department doing lingerie ads or something. What really distinguishes a cartoonist isn’t his skill as an artist – it’s his ideas, an inventive twist, the ability to see things in an arresting way. And that’s not a skill; that’s a gift.” Herman Goodden / Hermaneutics / The London Yodeller (4.10) May 12, 2016 |