|

ILLUSTRATION: ROGER BAKER

|

|

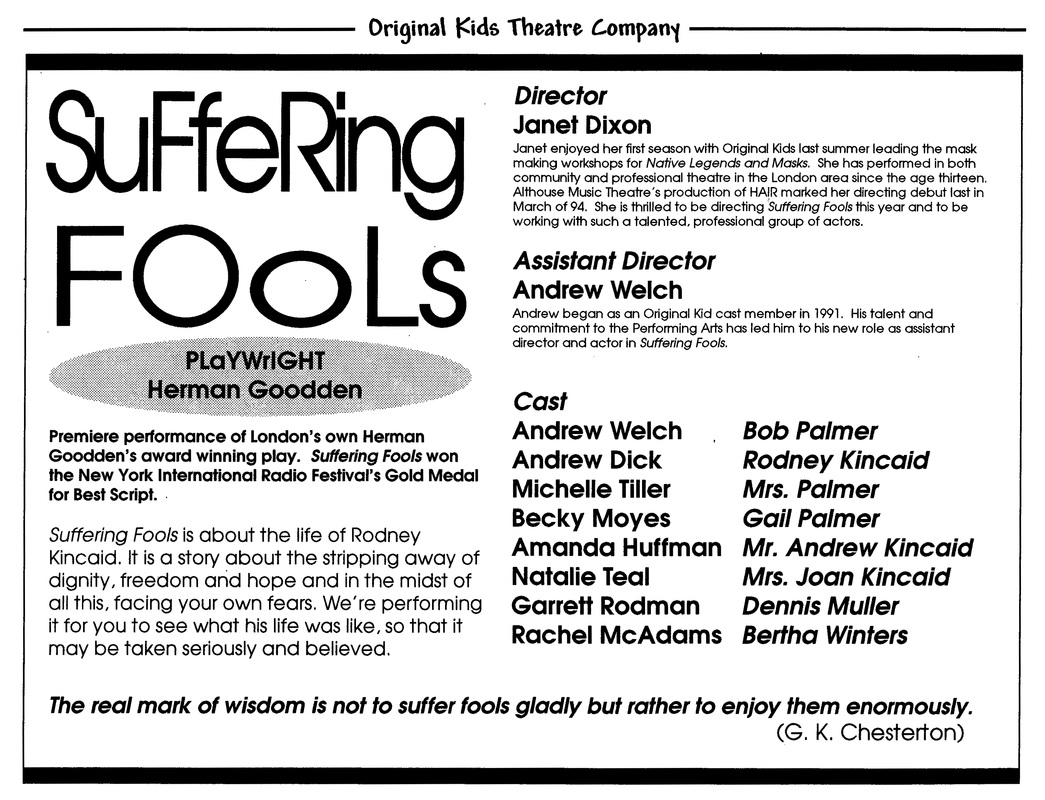

SUFFERING FOOLS

REVIEW: In some ways, Herman Goodden’s Suffering Fools is a familiar play. Its direct theatrical self-presentation, along with its staged resurrection of the dead and gone, have distinct flavours of Our Town. Its central figure, the developmentally challenged Rodney Kincaid, could be an early study for ‘Forrest Gump’. Suffering Fools was first performed in 1988, six years before we met Forrest. But interestingly, 1988 was also the year of Dustin Hoffman’s ‘Rain Man’. The topic was in the air. That topic, also familiar, is society’s careless forgetfulness when it comes to the real humanity of the developmentally challenged; the tendency not only on the part of official institutions, but even among family and friends, to treat the Rodney Kincaids of this world as objects without feelings, lower beings without human worth. To Rodney, this forgetfulness is full-blown betrayal, and Goodden’s play draws strong energy and poignancy from Rodney’s anger and his hurt, his despair and his dreams, and perhaps especially from his remarkable self-awareness. The situation is simple. In the aftermath of a failed suicide attempt, Rodney’s unfailingly loyal friend Bob has decided to exorcise some of Rodney’s demons, and to enlighten some of his past and present tormentors, by turning Rodney’s life into a memory play, performed by the actual figures from his life story. The characters in Rodney’s play, the living and the dead, are seated in a semicircle upstage, coming forward to play their scenes as they are called. Some are made to witness the damage they have done. A few, like Bob’s mother, are quietly honoured for the care they have shown. All are led toward new knowledge of a fully-feeling human being whom they have not properly considered. The play, then is constructed from an intense series of reconnections among Rodney and the real-life characters in his play; all managed by Bob. Together we return to humiliating grade school incidents, we taste Rodney’s raw anger at having wasted 23 years in a sheltered workshop, we feel the poignancy of his romantic devotion to a woman who has never noticed him. Dramatic conflict is everywhere – in the collisions between Rodney and the world around him, and in Rodney’s own traumatized reluctance to relive some of the scenes Bob requires of him. As in real life, some of Rodney’s stories end in enlightened contrition and reintegration on the part of the people among whom he has lived, while others, perhaps more, lead only to defensive self-justification or to indignant rejection. But this is not a despairing play. Suffering Fools moves to a triumph of personal wish-fulfillment, a suggestion like those in Shakespeare’s last plays, of the powerful capacity of the imagination to heal a broken world. In the last beat of the action, Rodney’s wounded relationship with his late father is recuperated through a moment of reconciliation (is it imaginary? is it real?) that reaches both back through death and ahead into the future. RODNEY: I don’t want to go out that door. I know what happens. It just gets worse and worse. You die and Mom dies and I start living alone and the only time anyone ever talks to me is at the workshop . . . Please, Dad. Can we just talk a little? MR KINCAID: (Beckons him over, RODNEY sits with him on the cot.) We’ll end it here and then we’ll have our talk. All right? (RODNEY nods his assent, MR KINCAID looks out to some invisible technician.) Okay, if you could bring down the lights, this is how we’re going to end the show. (MR KINCAID takes RODNEY into his arms as the light slowly fades to black.) - Skip Shand, Seven Short Plays from Theatre Ontario |

BELOW: Original Kids Theatre Co. production at London Regional Art & Historical Museums, 1995