|

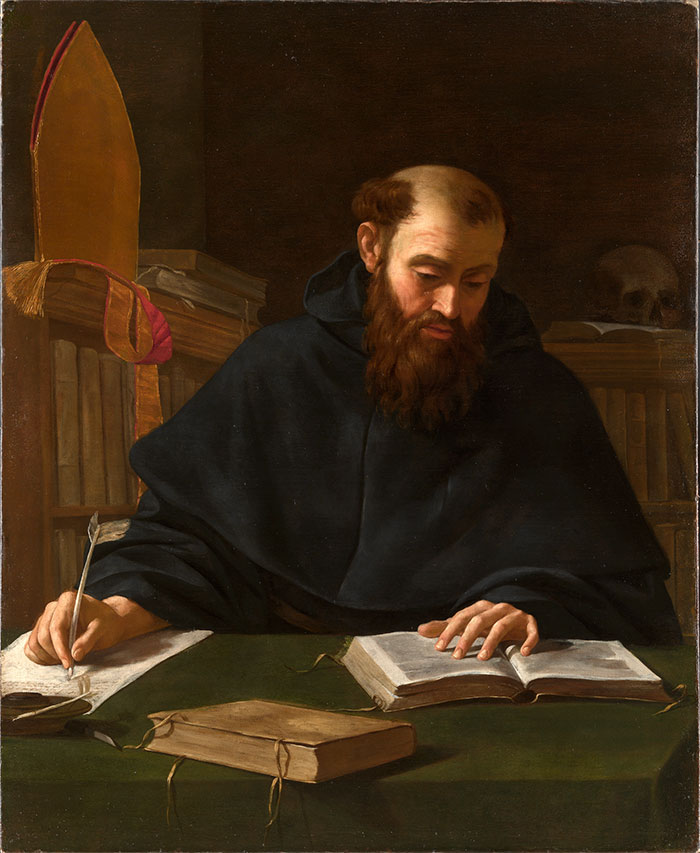

ST. AUGUSTINE BUILT A BRIDGE BETWEEN TWO WORLDS

HAVING RECENTLY STRETCHED myself quite fruitfully with my reading of The Divine Comedy on the occasion of Dante’s 750th birthday, this year I decided it was time to finally immerse myself in the writings of St. Augustine (354-430 A.D.) and read the two works for which he is best known, Confessions and The City of God. If you require a significant milestone to jog your historical reading, then by all means take advantage of this 1730th anniversary of his baptism to acquaint yourself with this incomparably influential ‘Doctor of the Church’. After sacred scripture and documents produced by various ecumenical councils, no authority is cited so frequently in the Catechism of the Catholic Church as St. Augustine. Incredibly, though he pre-dates Dante by some 900 years, St. Augustine is a much less formidable and more immediately engaging read. Partly this is because with St. Augustine you’re reading translated Latin prose, not Italian poetry. But I expect this ease of access has at least as much to do with the more pastoral and often playful cast of this great saint’s mind. I started with his earlier work written shortly after he was ordained Bishop of Hippo in North Africa, Confessions; the very first autobiography as we understand the term today. While recounting his childhood and young manhood and his meteoric rise as a widely respected orator and ‘vendor of words’, he also spins off, like some fourth century Malcolm Gladwell, a series of wonder-drenched speculations on the nature of memory, time and knowledge, the formation of character and the stubborn hold exerted on the human soul by habit and vice. Here is St. Augustine on how tricky it can sometimes be to express those truths so foundational that we’ve never paused to consider how we know what we know: “If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asks, I know not.” And here he expresses the three dimensionality of time by analogy to the recitation of a beloved poem that we know by heart: “The life of this my action is extended into the memory, on account of what I have said, and into expectation, on account of what I am about to say; yet my attention remains present and it is through this that what was future is transposed and becomes past.” St. Augustine’s recollections are peppered with expressions of revulsion for his sinful ways. As a boy he could be selfish and headstrong and a thief. And as a young adult shinnying up the greasy pole of social and occupational advancement, he was disgusted with himself for his pride and his greed, his shameless flattery of the rich and powerful and, most of all, his frequent capitulation to the siren call of lust. Far be it from me to suggest improvements to the moral temperament of a saint but I must admit I sometimes wish in this regard that he’d given himself a break. Though he eventually came to reject Manichaeism (a religious philosophy of bifurcation that saw matter forever at odds with spirit) I can’t help but suspect its continuing influence when, following his conversion, he had his long-time mistress and mother of his son (a woman he’d always treated decently and indeed loved) put away instead of marrying her. The commonest complaint one hears about St. Augustine as a philosopher of religion is that he was not a systematic thinker – unlike, say, St. Thomas Aquinas (1224-74) with his magisterial Summa Theologica. A beautiful writer, yes, and an omnivorous reader and a profoundly observant, compassionate and curious individual. But as a theologian we are told repeatedly (and perhaps just a little resentfully by more academic scholars of infinitely less renown and influence) that St. Augustine lacked rigour and torque. So how can we explain his undisputed position as the greatest of the Fathers of the Western Church (it was St. Augustine who first formulated our doctrines of grace, original sin and the Fall) and as a major shaper of Western civilization itself? For one, there was his popularity and the sheer volume of his writing. The man is estimated to have written 113 books, not to mention countless letters and sermons. He was also writing early enough in Church history that he was the first to stake out a number of themes and subjects and was writing in a time and a place when people urgently needed answers to existential questions. During his final years, a decade and a half when St. Augustine worked on that monumental capstone of his writing career, The City of God, in which he synthesised world history in the light of Christian principles, Rome, the controlling and nurturing centre of an empire that straddled the known world, had been sacked by invading vandals and other supplementary centres were being picked off and overrun one by one. The city of Hippo in North Africa where St. Augustine presided as Bishop was under siege as he lay dying. To get a sense of how utterly discombobulating this was to people everywhere, consider the chicken-without-a-head freak-outs we’ve seen around the world this year as an unorthodox president has assumed power in that great nation to our south which is at least still functioning and, in some regards, apparently thriving. The Catholic historian Christopher Dawson writes that this tectonic fifth century shift “was no ordinary political catastrophe, but ‘a day of the Lord’ such as the Hebrew prophets describe, a judgement of the nations in which a whole civilization and social order which had failed to justify their existence were rooted up and thrown into the fire.” Unlike other contemporary writers and thinkers such as Tyconius, St. Augustine did not assume that the fall of Rome was a sign of the end times and in The City of God he sought to comfort and strengthen his rattled flock by formulating a way forward and to help his people cope with life in this never more dangerous world. Taking inspiration from numerous scriptural sources (consider St. Paul’s “Here we have no continuing city”) he posited the existence of and delineated the differences between the City of Man and the City of God. At first blush, this may seem like more recycled Manichaeism but it is in fact dualism because there is a bridge between these cities forged by Jesus Christ who has promised he’ll be with us until the end of time. St. Augustine tells us that the animating principle in both cities is love: “Two loves built two cities – the earthly, which is built up by the love of self to the contempt of God, and the heavenly, which is built up by the love of God to the contempt of self. [These two cities] have been running their course mingling one with the other through all the changes of times from the beginning of the human race, and shall so move on together until the end of the world, when they are destined to be separated at the last judgement.” In the same sense as Catherine of Siena when she wrote that, “All the way to heaven is heaven, because Jesus said, ‘I am the way,’” St. Augustine’s dualism does not call for a rejection of the City of Man. Rather he instructs us to properly align our love (as that is what will ultimately shape us) and to cultivate gratitude for the gift of this difficult and heartbreaking world for which God cared enough to give his only Son, this world from which we too set out on our journey to The City of God. In Confessions St. Augustine movingly expressed this generosity of spirit which I find so characteristic of the man at his best, when, reflecting on his conversion, he wrote: “I no longer wished for a better world because I was thinking of the whole of creation, and in the light of this clearer discernment I have come to see that, though the higher things are better than the lower, the sum of all creation is better than the higher things alone.” Herman Goodden / The Catholic Register / October 1, 2017 |