|

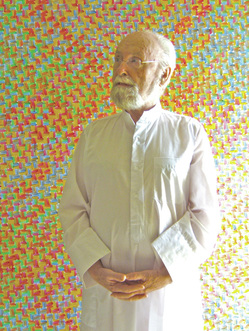

Ross Woodman

Photo: Kirtley Jarvis

|

A TRANSFORMATIVE TEACHER AND A GREAT SOUL

WRITER, ENGLISH PROFESSOR, art patron and critic, Ross Woodman died quietly in his sleep on the first day of spring in his art-filled north London home that was once a convent. Though he was 91 years old and for the last 20 of those years had been known to occasionally answer the question, “So what are you doing lately?” with the single word, “Dying,” family and friends were nonetheless shocked by — or at least totally unprepared to face — his passing. Ross had been suffering extreme levels of stress just lately caring for (and arranging for others to care for) his wife Marion who is assailed with dementia. This was probably a contributory factor to his death, though not one he would have foregone for the sake of preserving his own health. The Woodmans’ marriage was a rare match of profound depth. They had first met when Marion was Ross’ teaching assistant for a full year at Western. “We had a wonderful time,” Ross told me. “But I knew there was quite a fundamental difference between us. I said, ‘You know, Marion, your first and primary interest is not literature, it’s the students. You look at literature in terms of soul-making. And my attitude is a much more academic one.’ I was interested in literature as an end in itself. I came to see that our two patterns were complementary rather than antagonistic.” Indeed, Ross would identify the “hidden dynamic” of their marriage as “the coming to the feminine through the masculine and the coming to the masculine through the feminine.” Marion needed Ross to help her cultivate incisiveness and discrimination. Ross needed Marion to draw him out of a too compartmentalized, too abstracted world view. They married in 1958 and Marion became a much-loved teacher of English and theatre at South Collegiate while Ross stayed on at Western for almost 40 years, specializing in the Romantic poets. If Ross had a ‘main man’ in the pantheon of English poets, it was probably William Blake with whom he shared a birthday. It was during the early years of their marriage that Ross began to collect and write about art, producing a body of work in the form of nationally published books (on painter Jack Chambers and poet and playwright James Reaney) and articles and catalogue essays that brought coherence and attention to the work of at least two generations of London artists. I’ve often wondered how much of the buzz that London artists generated in the 1960’s would’ve been possible without Ross’ essays in Canadian Art and The Globe & Mail. And how many London artists might’ve thrown in the towel (or at least succumbed to despair) if Ross hadn’t bought their work. Both Woodmans had an uncanny ability to draw out even the shyest and most alienated of their students and awaken them to their own deepest mysteries and potentialities. It wasn’t an approach that every student appreciated but for those whose antennae could pick up the Woodmans’ signals, they were major, life-shaping teachers. In the mid-70s, Marion decided to take her soul-making work onto the next level and quit her teaching job, traveling to Zurich for seven years where she studied to become a Jungian analyst and — eventually — a best-selling author of a series of books exploring psychological dimensions of the feminine and the masculine. Initially this major shift of Marion’s put a definite strain on their marriage. I remember dropping in on Ross one muggy summer night during that rather rough patch. Their house up near the university was dark but during those half-attended years with Ross rattling around the joint on his own, darkness didn’t necessarily signify absence. (I don’t think he turned the downstairs lights on once during the summer of the Watergate hearings when he pretty well lived in his bedroom glued to the tube in a state of morbid engrossment.) On this night, eventually, he answered the door in his bathrobe, blinking a little at the streetlight’s glow and invited me into the living room, casually adding, “Now, watch you don’t step on Marion.” Indeed, Marion was home on a flying visit from Zurich and as her back was giving her grief, she was stretched out on the floor simultaneously trying to realign both her lumbar vertebra and her marriage as she and Ross talked in the dark. Clearly it was a bad time to come calling and I took my leave just as soon as I graciously could; fearing during my walk back home that this union of two such wonderful souls really might be knackered. But they came through and grew from that period of trial. I first met Ross face to face in the winter of 1971-72 when a group of bohemian keeners who were studying theatre and/or philosophical English with Marion at South Collegiate (a course which included study units on such meaty fare as The Book of Job and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot) decided to hold a dinner party for their favourite teacher and that utterly unknown quantity, her husband, who proceeded to steal the show. We held the party at the home of a student whose parents were away in Florida so we had the house to ourselves. In the evening’s very set up -— eight or so teenagers putting on a precociously grown-up dinner party — there was already a sense that we were perched on the brink of a new and more adult phase of our lives. And this Ross graciously and generously confirmed by going around to each young member of that party in turn and deftly drawing them out, getting them to talk about their dreams and aspirations and making them feel understood and affirmed in a way they had never known before. At Ross’ funeral service as speaker after speaker stood up to talk or had their messages read out about his impact on their lives — whether it was a visual artist, a psychoanalyst, a professor, a carpenter, a filmmaker, a musician, a shopkeeper, one of his students, his nieces and nephews or his little sister — the import was the very same as what that group of callow kids had experienced at that dinner party 40-some years ago: ‘this wonderful man understood me in a way that helped me so much and gave new meaning to my life.’ When I learned that Ross had died I pulled out my copy of The Apocalyptic Vision in the Poetry of Shelley just for the comfort of holding something of his making in my hands. Shortly after I’d bought that copy of his book I asked Ross to inscribe it for me. “What’s she done for me lately?” he asked, scratching out Marion’s name with a chortling laugh in the printed dedication and inserting mine in its place. Just below that he wrote, quoting Shelley’s Adonais, in which is suggested the liberty of the soul after all earthly bonds are loosed: “Peace, peace, he is not dead, he doth not sleep — ” Herman Goodden / The London Yodeller (2.8) / April 10, 2014 |