|

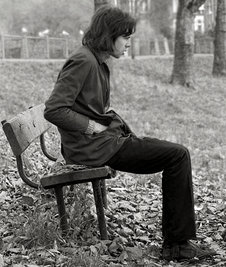

NICK DRAKE

CAN A TALENT THIS TENDER POSSIBLY ENDURE? IT WAS 40 YEARS AGO this winter that Nick Drake, lying low at his parents’ comfy Warwickshire home and depressed out of his gourd because his life and his brain and his musical career were all spiralling out of control, killed himself by ingesting more than 30 Tryptizol anti-depressant tablets. He was 26 years old and left behind three arrestingly melancholy albums of utterly original songs – Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971) and Pink Moon (1972) – that hadn’t sold worth spit or garnered much in the way of critical attention during his lifetime. And then, of course, as is the maddening way with such things, death was the charm or the key that - gradually at first and then more and more completely - finally forced some movement within the seized-up padlock that had so cruelly kept him tethered to the earth. And as the legend of Nick Drake started to lift away and attain ever loftier heights of elevation, the tortured musician increasingly came to be seen as this romantic, Byronic figure whose heart and whose gifts were too pure for this world. If he could somehow be resurrected for a day, what would this unusually private and gentle soul make of the nearly 500 page monument to his life and career and influence that his sister, the actress Gabrielle Drake (most famous at our house, at least, for playing Inspector Lynley’s mum, Lady Asherton) has lovingly assembled and published this year as Nick Drake: Remembered for a While? Emily M. Keeler writing last week in The National Post, empathised with the impulse but declared the book disproportionate; calling it, “an exercise in exquisite futility: Despite what we may wish, there is simply not enough material to make Drake into the master we long for him to have been . . . the project in the end feels hollow; no matter how deeply Drake’s loved ones may grieve him, the man who made Pink Moon is gone, and he left so little behind that we’ll never get enough.” I wouldn’t be so hard on the book or the man. I can think of a lot of important musical acts whose catalogues are similarly truncated and yet who managed to put enough across to constitute a significant legacy – the original four-man Traffic, Arthur Lee’s original Love, the horrible old Sex Pistols and the good old Mutton Birds. Drake might have had a fighting chance at minor star status if he’d been willing to get out there and work the clubs but he loathed performing. Describing one of Drake’s few live appearances, good friend, fellow musician and Island record label mate John Martyn said, “He was cripplingly nervous. It was rather embarrassing in fact to see him. I mean the music was fine but he just didn’t like being there at all. I got the impression it was costing him too much to go on the stage. It was like no amount of applause or anything else would ever have paid him back for the mental energy and effort he had to expend.” Drake longed for other singers to interpret his material and leave him free to compose. I used to think that was a vain and desperate hope, not being able to imagine any but his own ghostly voice doing justice to an idiosyncratic jewel of a song like Northern Sky from my favourite of his albums, Bryter Layter. But a recent viewing on Youtube of a 90-minute BBC tribute concert, Way to Blue: The Songs of Nick Drake, with the participation of folks like Teddy Thompson, Robyn Hitchcock, Kate St. John and Danny Thompson changed my mind on that score. Other people can do wonderful things with the Nick Drake canon. Drake’s record company, his producer and a handful of fellow musicians all stood by him through his three year decline with schizophrenia in a way that would be quite unthinkable today. But Drake’s confidence had crumbled away beyond the point of retrieval. The leaner, stripped-down sound that had so distinguished Pink Moon (it remains his best-seller to this day, largely helped by the title song’s appearance in a sublimely effective 1999 TV advert for the Volkswagen Cabrio) had given way in subsequent material to a jarring, half-finished crudeness. There were a few clumsy and sporadic attempts to lay down tracks for a sketchily perceived fourth album but Drake took himself out of the picture before anything was finished. There are some sensitive souls (such as the one I married) who can’t listen to any Nick Drake as the sadness of it seeps into their bones and unnerves them. I feel that way about those final orphaned tracks which have been released as bonus cuts on various compilations – particularly one called Black-Eyed Dog where his guitar playing feels panicky and he sings in this awful higher register and sounds like a terrified kid. Among the more remarkable essays and documents that Gabrielle Drake has assembled in this hefty tombstone of a book, is the diary that Nick’s father, Rodney Drake, kept for the last two and a half years of Nick’s life; a diary exclusively devoted to his observations and concerns as his only son fell apart before his eyes. Bewildered and scared, the poor man and his wife Molly are put through the wringer as they try to affix a workable grip to this mercurial process of dissolution. When they invite Rodney’s sister Pam who is suffering from Alzheimer’s to stay with them for a period as well, things take a turn for the surreal: “Sunday 18 November 1973 We returned to find Nick sitting in the drawing room watching TV with Pam who seemed pleased that he had sat with her but unable to recall if any words had passed between them.” And then a few weeks later: “A strange meal with Nick gazing in utter gloom at the floor and Pam standing about not really knowing what to do next but seeming unable to relax and sit down. Would all make a good Chekhov play no doubt but not a very happy one in which to find oneself participating.” With fond testimony from family members, childhood and university friends, producers, engineers and fellow musicians who helped out on his recordings, Gabrielle’s book highlights a sort of paradox that its subject would have appreciated. It’s a funny thing to say about a figure so apparently doomed but Nick Drake was a lucky man to be surrounded by such good people who loved him so much. Herman Goodden / Hermaneutics / The London Yodeller (3.01) Jan. 8, 2015 |