|

“It’s nothing if a loser loses. But when someone with so much force, energy, potential blows it or it all slips away or those same great energies turn destructive – that’s the stuff of tragedy.” – Father Joe Nelligan

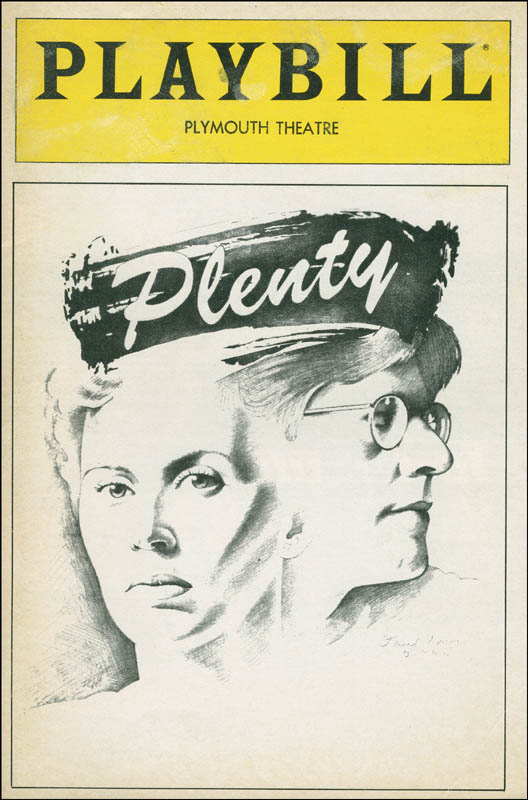

THE NELLIGANS HERE'S AN OLDIE but a goodie that was first published in London Magazine in 1985 under the editorship of Douglas Cassan who felt that telling stories about families was a great way to dig a little deeper into London. Was it ever. Actress Kate Nelligan’s star was rising at that time and I thought I might be able to get access to her through her younger sister, Mary Jo Jansenberger - an outrageously funny contemporary of mine at South Secondary School who had always been friendly with me even though we mostly moved in different circles. At first Kate wasn’t inclined to talk with me at all but as Mary Jo and two of her other siblings did, and as they started exploring a far more riveting family drama than the charting of an actress’s ascent, Kate consented to speak with me after all. I was deeply honoured that they’d entrusted their story to me and wanted to do it justice. I had transcribed hours and hours of one-on-one interviews with these wonderfully insightful and eloquent people and sometimes had all four of them recounting the same incident. How was I going to get all their best bits in without repeating the same material over and over again? And how could I minimize my own presence as an explainer and an arranger and just let them tell their own story? After I’d written about ten paragraphs of introductory narrative, I took the scissors to my transcripts and laid out the rest of the 15-page story like the script of a play, freely cutting from one speaker to another. My father who almost never commented on my work told me it was ‘terrific’. And with my own eyes I saw Douglas pull ads off the proof sheets to make room for the whole thing when it was published in the September issue. It was working on this piece that made me start thinking about trying my hand at writing plays. - Herman Goodden KATE NELLIGAN USED HER OLD HOME TOWN like a swimmer uses the wall of a pool. As a very ambitious, complex and highly charged sixteen year old kid, she assumed the lightest of grips on the rim of that pool, set her feet against the wall, collected all the strength and energy she could summon into her legs and kicked off into the great unexplored centre where no Londoner had ever gone before. She has worked her way to the very pinnacle of the theatre world, both in London, England’s West End and on Broadway. She has been acclaimed as the leading actress of her generation by Sheridan Morley in The Times and The New York Times singled out her role in the 1983 American production of David Hare’s Plenty as the finest performance of the Broadway season. London’s claim on Kate Nelligan has been minimal. Her appetite for the stage was barely established by the time she left us and when talking to the world press about her career in acting, she never thinks to mention her two forays into public speaking at South Secondary School – her first speech was indeed dramatic; she passed out on stage and collapsed into the arms of a nervous fellow student – or the larger part she played in South’s Centennial drama and music revue entitled (cringe) Sap & Syrup. Whatever inspiration she’s drawn from this town has been predominantly negative; it was something to get away from. “I don’t have very good memories of being a child,” she has said. “I knew I had to get out . . . out of that neighbourhood, that town and that country. I knew I was not going to end up in one of those little houses.” This is a quote that never seems to turn up on the cover of pamphlets published by London’s Visitors and Convention Bureau. Kate has never been willing to engage in idle chit-chat for the gang back home, gives a claustrophobic shudder whenever the Free Press prints another headline extolling the latest news about ‘Our Kate,’ refuses to be turned into this city’s thespian equivalent of Slippery the Seal. Relations between the Nelligan family and the media in London were always fitful, mutually torturous and bewildering until April of 1979 when a rupture of decorum shut down communications completely. Kate was in town to visit her family and play doting aunt to her newborn niece Emily and didn’t bother to take up the Free Press’ open invitation for an interview. Hell hath no fury like a hometown scorned and Richard Newman, normally one of the most sensitive and reasonable journalists to ever work in this town, lashed back with a sizzling piece of invective, calling her ‘cool Kate,’ ‘gentle Kate’ and ‘beautiful Katy’ as he recalled the $700 that the Free Press had laid out to send a reporter to cover the ceremony when Kate won The Evening Standard’s Actress of the Year Award in London, England. “Londoners have been thirsty for knowledge about the girl they knew as Trish Nelligan in public and high school . . . It would have been an oh-so-small gesture to show her face and let her fellow Londoners beam a little on artistic success. Guy Lombardo never forgot Londoners. Hume Cronyn has never lost track of his London links, and cherishes friendships and relationships with his home city.” The comparison with Hume Cronyn was partially apt – he is at least an actor and a very good one too – but as the privileged son of one of London’s oldest, wealthiest and best-established families, his experiences and impressions of the Forest City couldn’t have been more different from Kate’s. There were five children born to Pat and Jay Nelligan on Little Grey Street in East London, a neighbourhood that was crawling with relatives and family history. The firstborn child and only son is Joe, now 41 years old, chronically ill and very much alive. He is a priest for two Huron County parishes, lives and works in Mt. Carmel, has served other parishes in Windsor, Tilsonburg and San Diego. He is the keeper of the Nelligan family archives and as he sucks back beers and leads you through more than a century of complex family history, his voice takes on the Irish lilt of his ancestors and his eyes grow ever more intense and bright with the pride and excitement he feels for the story of his people. As one who still listens to and learns from the dead, remembers their deeds and honours their memory, it seemed fitting that our second conversation took place in the parish graveyard in Mt. Carmel at dusk on a cool evening. The oldest daughter is Jan, born in 1946, phys. ed. teacher extraordinaire, now living in Agincourt, newly married and raising two children. Notoriously shy, she turned down my invitation to talk. “Here’s what you have to get down about Jan,” said her sister Mary Jo. “She’s the nicest of the lot and she’s the only Nelligan who knows how to bake a pie.” In 1950 came Particia Colleen Nelligan, known to most of the Western world as Kate. She’s been having her say in the press for years now but in this story of the Nelligan clan, she appears more often as a subject than a commentator. Mary Jo was born in 1952. (“Joe named me. He was eight years old and desperate for a brother so that explains the ‘Jo’.”) She and Kate represent the two sides of the Nelligan coin. They couldn’t be more different. They couldn’t love each other more. She’s the mother of three daughters, a Montesorri teacher and the wife of a chiropractor who lies flat on his back on the hardwood floor to watch TV. It’s interesting to contrast Kate’s dread of “those little houses” with Mary Jo’s domiciliary destiny. She now lives a mere block and a half from her family’s old home on Briscoe Street and pats her chest in relief after recounting the four years she spent at university, compelled to live on alien turf. Terri was born in 1956 and bears a striking resemblance to Kate (who, in turn, resembles their mother). After an extended adolescence she is now pushing her way through Althouse College to become a teacher. “I really mean it, this time. I’m a long distance sort of person but I’ll get there.” Terri, like many of the Nelligans, has a surfeit of potential. She has taken thoroughly credible stabs at the worlds of drama, journalism and athletics but now discounts or minimizes all of them, believing that with teaching she’s found the profession that will fully support that other pronounced Nelligan attribute – will. These are the five and this is their story; let them tell it in their own words. |

|

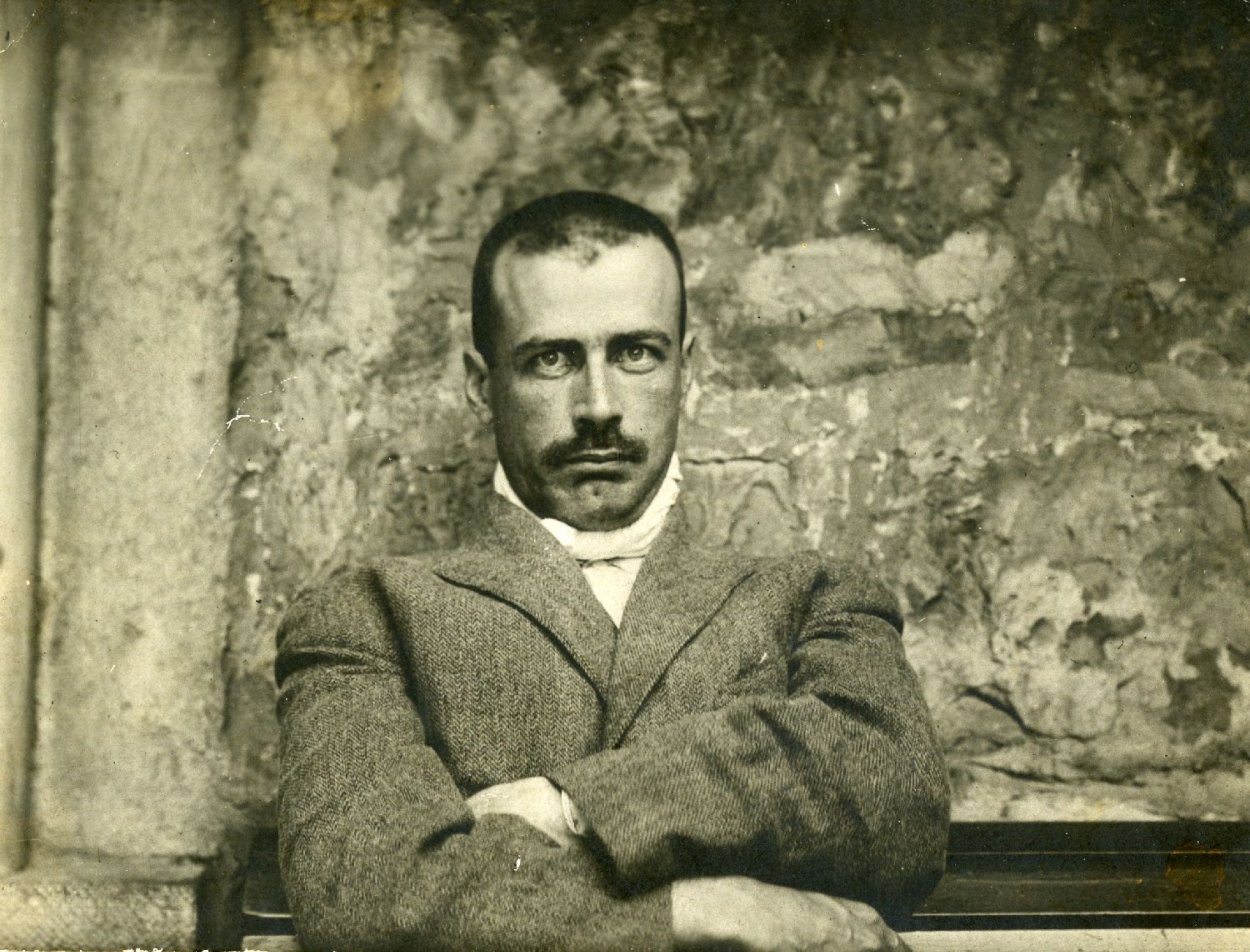

JOE: The first batch of Nelligans came over from County Down on a cholera ship in the 1850s to escape the first potato famine. They were quarantined in the St. Lawrence and a bunch jumped ship and became Francophones. One of them fathered Emile Nelligan, one of the great French Canadian poets. He was a magnificent talent who went stark raving mad at the age of twenty-three and spent the rest of his life in an asylum without writing another word, was almost seventy when he died. The rest of the Nelligans came west and my grandfather was born in Petrolia in 1890, married my grandmother in 1914 and paid for their home in East London before he even moved in . . . My father Pat and his four brothers were all born in that house and were expected to take their place in the industrial Irish establishment of East London, finding employment with the railroad, Petrolia Barrel Works and other east end concerns. Two of Pat’s brothers to this very day are still living on that same block. And the three who got away all had to overcome stern opposition from Grandfather. First there was Pat’s brother, Barry, but he was a lawyer, the family rebel, so he probably got out the easiest. Then my Uncle Joe, Pat’s youngest brother, built his house on Creston Avenue in 1948 – and that whole area was actually outside London until annexation in 1960. Well, Grandfather went crazy. He was just furious. “You’re a Nelligan. You’re supposed to be in London and you’re supposed to be in East London. By God, why the hell don’t you move out into the middle of Lake Erie? Or go to St. Thomas for all I care! You’re a jerk! It’s not even in the city. There’s Apaches out there; threatening bands of Indians! And you’re moving your wife and kids out there? You’re a jerk!”

I was born during the war while Pat was in the Navy. I ended up living at my grandparents more than at home. They just lived a block and a half away, Jay was still teaching so I gravitated to them. They’d raised five boys and I was the first grandson which meant I was accorded all the respect due to royalty. It worked out well as compensation or balance because Jay was an incredibly demanding mother. It was important to Jay that her children be exposed to options, and, in her less than subtle way, that we be encouraged to take the option that would provide the greatest opportunity for self-realization in return. If you are gifted, you will be expected to produce and to reap the rewards of that productivity. You must not stagnate. You must not reduce your horizons. You will not be allowed to settle for mediocrity – that was her greatest enemy. Compare yourself to no other person but you will not tolerate within yourself anything less than your personal best. Once you’ve chosen an endeavour, it must bear your talisman. You sign it yourself and therefore excellence must proceed. The bottom line is not the return you get but your signature. I’m so grateful in the light of history that I had such a person in my life but to have had my mother to the exclusion of others would have been totally devastating. MARY JO: My mother paid particular attention to three of her children – Joe, Tricia and Terri. I really feel that me and Jan were the lucky ones, that we emerged unscathed. I used to get so disturbed sometimes when Jay came into the room. It was like being around a hurricane. JOE: Luckily, I had the compensating, affective emotional stability of my grandparents who were an old-fashioned couple – Irish, cuddly, sweetcakes, incredible vegetable soup – stuff like that. My grandfather worked for fifty-one years driving steam locomotives for the CNR, started at the age of fourteen. He’d driven the King and Queen from Toronto to London in 1939 on the Flying Scotsman. And he drove Queen Elizabeth in 1952. Diesels were introduced in 1951 and he simply refused to drive one and they kept them off his run until he retired in 1954. I idolized the man. He grew roses. This strong man who moved these great machines also had that kind of sensitivity. The poet and the peasant. Jay was more directive. It was an implied standard with him; I just wanted to live up to his example. My grandfather never lost his job all through the Depression and had a soup kitchen at his back door for anybody who needed it. And after the war he loaned money to newly arrived immigrants from Italy and Poland. There must have been twenty or twenty-five of these men. Grandfather would lend them money to make down payments on these small East London homes so they could set themselves up and send for their wives and kids to join them. And I remember some of those men coming around to the house to make their payments. They all seemed to ride bikes and wear peaked caps. Grandfather would invite them in, they’d do their business and then they’d have to have a smoke together and talk. Something more than just business. “I owe it to them,” he told me once. “We never lost a day’s work. My children never went hungry. These men fought in the war and paid a very noble price for all of us. I owe it to them.” When I was in the second grade I stole a half-track truck from school. It was a stupid thing to do. Even before I was caught it brought me nothing but anxiety. I’d been punished at school and by my parents and I begged them not to tell Gramps. If he ever found out, I just didn’t know how I was going to face him. Well, they did tell him as I found out shortly. First thing he said: “Joe, I hear you’ve done such and such but I had to hear it for myself. Is it true?” “Yes, Grandfather, it is.” This man was everything to me. Nothing could’ve been worse than what he said next: “Get out of my sight.” The world was over. I got on my bike and cycled for miles down the river, crawled into an empty oil drum and just wanted to die. It was hours later the police found me and took me home and Gramps said, “I’m sorry for what happened but you have to understand that I would see you dead before I’ll ever see you as a liar or a thief. The most important thing you have is your reputation and once you’ve destroyed that, you’ve given away your soul.” MARY JO: The great push west set in right after Terri was born. Jay knew Terri would be the last kid so she went back to university to upgrade her teaching degree. It had all been public school before. Now she was going to teach high school. Pat’s family were all out east. The move to Briscoe was entirely Jay’s idea. JOE: Of course, the move caused great division. Gramps thought Jay was becoming uppity – the house that my great-grandfather had built was no longer good enough – that sort of thing. But it was seen by mother as a necessary step if they were ever going to get out of what was obviously a deteriorating neighbourhood. We’d all loved that neighbourhood and some of the characters but ultimately, Jay was right. Negative influences were encroaching and she was thinking of her kids; what neighbourhood would offer them the most. There were the beginnings of gangism and stealing; just the kind of language you’d hear in the street. And don’t forget Jay had four daughters and virginity was not a highly prized commodity out there; nor did it last very long. TERRI: I’m very proud of our East London roots; they’re very much a part of our family. There was an attitude to work that was instilled in us from the very beginning. Whatever it is you do, you give it your very best and you take it seriously. I admire that and I try to honour it. Even when I was a dishwasher, I was the best dishwasher I could be. JOE: My mother was very disappointed with my decision to enter the priesthood. Her contention was that those who will come to benefit from what you have to say and be are holier than you already, so they don’t really need you. The people who regularly go to church will be there no matter who happens to be standing at the front, so I won’t really have the scope to influence anybody. She thought I should go to law school. “You’ll meet the same kind of people who are having problems but you’ll be able to provide yourself with a wife, a home and $250,000 a year and ride the crest of their problems and charge them for it. Whereas this other way, you’re going to deal with a limited segment of the population and you’re going to be an insufferable, impoverished, unpossessed and unfulfilled person and you’re not going to give me any grandchildren.” Jay was not a particularly religious person but she was a very spiritual person. My grandparents were devout Catholics and spending as much time with them as I did certainly influenced my decision to become a priest. My mother’s greatest resentment in her latter days was against my grandmother for alienating my affections. She said, “I could never be like Lucy. You worship Lucy, don’t you?” And I said, “No. In a way I did, yes, but you could never be a Lucy and you should never try to be. You were Jay and Jay was different.” Jay was the spark, Jay was the fire. Lucy was the comfort, Lucy was the down. A man needs soft and hard, warmth and light. And then when I became a priest, she saw that as the confirmation of Lucy’s values. But it wasn’t an either / or thing at all. There are many of Jay’s values which I know I’ve brought into the priesthood. And Tricia carried those same values into acting. There is a compulsion to be consumed by those around you – they must take up your energy. Every time they come out to Mass or pay fifty-five bucks for a ticket at the theatre, it doesn’t matter what the hell your feelings are – these people deserve my best. And that’s pure Jay; that striving to leave your best personal signature on something and to be a conduit – strive to convey something that’s truthful and worthwhile and important. Nothing else matters. Nothing else lasts. They even change Coke. TERRI: Occasionally we’d have dinner at the table. Certainly for Christmas. But usually it was TV trays or the countertop. We didn’t even have a tablecloth and it’s still a source of embarrassment because our table manners are awful. All of us, very consciously, have had to teach ourselves how civilized people eat. MARY JO: It’s not that we had no family life. It’s just that with Pat and Jay working all day, Jay working evenings to get her degree, Joe usually living at the grandparents, Trish running off to practice or lessons . . . dinners just sort of fell by the wayside. But there was always food and when it occurred to us to eat, there’d be a race downstairs to grab the champion spoon. That was the one good spoon that wasn’t all bent. The first major argument of my married life concerned this kitchen table. I was adamant: we’re going to have a table, we’re going to have dinners, we’re all going to sit together and talk. |

|

TERRI: There were a lot of TV dinners and we got into every fad food there was. Oh, and cereal and The Flintstones. Mary Jo and I would get under the stools and sit on the floor with our cereal and those were our caves. I was Betty and she was Wilma. I liked Betty because she had big eyes and was prettier.

MARY JO: We all ended up with our own surrogate families who could take us in for a weekend or a meal when we wanted to see how other people lived. I used to visit the Barry Nelligans on Mountsfield Drive and that house was so much fun. They had kids my age plus all these babies and we got to do anything we liked with the babies. We’d go to the beach and there were so many kids you wouldn’t get there until five in the afternoon. I can’t imagine people nowadays putting up with all that aggravation. It was great. TERRI: The recurring phrases for which Pat is chiefly known and remembered and impersonated always seem to be phrases of exasperation: “Jesus, Jay, just slow down and take it easy” and “All right, pack it up.” JOE: Our problems were always on the outside and very dramatically expressed. There’s a wondrous complacence to Pat, a hunger for stability which was probably never satisfied, but the man has an enormous wit and a sense of the ironic which all of us have inherited. There was an abrasive quality to his relationship with Jay but they also complemented each other. I would never presume to plumb the depths or pass judgement on the dynamics between them. Look at the results, that’s all. And Pat and Jay didn’t do too damn badly. They did remarkably well, I think. I’m very proud of them and what they achieved in their own way without knowing what they were doing. They provided a tiny little crucible from which there was a great deal of heat but there was also light; a bit of a meltdown but there was also something produced that was solid and enduring. And I don’t know what more you could ask of human parents. I think if you look at the children, you’ll see that each was somehow allowed or enabled to become his or her own person and achieve a level of success and happiness. MARY JO: Pat gets furious when he reads these articles on Trish that call him ‘blue collar’ or ‘working class,’ implying that we probably went hungry for weeks at a time. He works for the recreation department of the PUC. He loves his work, it pays well and he does it well. He retires this fall with a pension. Is that ‘working class’? Five kids puts a drain on any income but we’re not talking about destitution here. We weren’t your average middle class family but that had more to do with our personalities than our income. TERRI: I saw The Days of Wine and Roses on TV one night when I was just a little kid. It was my introduction to the subject of alcoholism. Consciously, at that time, I knew absolutely nothing about Jay and her drinking but on some level I must have suspected something because that film haunted me for months. MARY JO: I don’t think any of us remember the start of Jay’s drinking. Suddenly, you knew it was there, you knew it was big, but you also knew it had been going on for a while. TERRI: I remember following my Dad up the stairs when he came home from work. And watching him shave every night which just fascinated me. I loved the smell of the lather and the mechanical grease. And then he’d carry me to bed on his shoulders and tuck me in. School days, he’d pick me up and take me to lunch at the Ridout. In the summers I’d follow him around all day while he did the ball diamond at Labatt’s Park. It doesn’t sound like much fun but it was great to be out all day with your Dad on the job. And not too many dads back then would ever put up with their kids like that. Work was your excuse to ditch them. But Dad was always there and very easy to be with. I have this mental picture of the two of them – Dad sitting in his chair reading the paper with Mom sitting at his feet sort of hanging onto his legs. That’s why I laugh at feminists; they’d take one look at the physical relationship implied in a scene like that and jump to all the wrong conclusions. There was nothing political or unequal about it. It was just beautiful. They obviously had a real physical spark between them and I think it’s so good that we kids were able to see it at times like that. MARY JO: Ernie Harwell – that voice – he’s the commentator for all the Detroit Tigers’ games. I just have to hear his voice and I warm up inside. Pat and Jay were dyed-in-the-wool Tigers’ fans ever since they were dating so they’d always tune in the games. They’d sit on the front porch and the neighbours – Vic from across the road, Donna and Wells, whoever happened to be walking along – they’d all end up on our porch listening to the Tigers. And that was great because you could hear the radio in our bedroom from the porch. TERRI: Jay was always physically affectionate with me and materialistically, I always got special attention, lots of clothes. I was the baby, the special poopsie. She was always very warm to me but also I was always aware of distraction. I sometimes felt I was accepting the love for her sake, to appease her, make her feel better about what she couldn’t do for me. But now is when I really appreciate the osmotic effects of having had Jay for a mother. I think of how much life and energy and brains – everything that’s strong in us – came from her. And I thank her for that. And the bad stuff, I don’t hold it against her at all. Looking back now I can start to understand, to feel, even an ounce of the hurt and the anger and the horrible humiliation she must have had in being such a strong and gifted person and falling apart. She went through that process for more than ten years and to systematically destroy yourself that way . . . the inner pain that must’ve caused . . . to watch her household and her profession all falling to pieces . . . the loneliness and estrangement. There isn’t a day goes by I don’t think of her and feel terrified at what she went through. Academically, she was an ace and I think she should have specialized in that. But instead she tried to do what everybody else did at the time which was get married and have children – in her case, five – and I think she realized a little late in the game just how important her career was to her. So she didn’t balance it at all well, she couldn’t, and she was never able to cut back on one thing in order to focus on another. And that was her downfall. MARY JO: I’ve learned from Jay’s mistakes. I learned really early in the game that nobody can have it all. There are a lot of women right now – a lot of my peers – who are making Jay’s mistakes. They want the magnificent career, the social life, education, the ultimate family, perfect children – all the marbles. I watched Martha trying to grab all of her toys and go up the stairs one day. And she wouldn’t put them down because she didn’t want her sisters to get them. She wouldn’t even take them up some at a time. She had to have them all right now. And she fell and really hurt herself. And I sat there, watching this, and I thought – that’s the story of Jay’s life. TERRI: By the end of her teaching career I think she was just winging it all the time. When I was younger she always brought home lots of marking and stuff to read and later on there was less and less. She kind of bounced down one rung at a time: got drummed out of CCH, then adult education, then English as a second language. I remember overhearing her and Dad talking late at night, the fear and anger in her voice as she talked about her boss. She never played the game very well. Not intentionally – she just didn’t seem to understand how to work in that sort of system – how to turn yourself down that low, become that invisible. I guess she got into trouble once for showing up at work wearing purple stockings. Just scandalized the nuns. And I know she didn’t do that on purpose. To her, they were just stockings. MARY JO: When Trish started walking at eight months, she was marked for greatness . JOE: Tricia was a super over-achiever. You name it, she took lessons in it. Excelled in all kinds of athletics, played tennis competitively. She was accelerated through early school so that she entered high school at twelve, won her scholarship to York University at sixteen. She later felt she was unduly driven by Jay and certainly there was a lot of pressure. She didn’t have any real teenaged happy days – rock & roll down at the bistro, that sort of thing. Not that she would have appreciated or benefited from it anyway. Her personality, her demands, her values, her sense of humour – as my own – tended to be biting and incisive. We made high demands on ourselves and those around us and had great fun and sport with other people who were more passive and reticent. Tricia was intolerable. So am I. No one could ever live with us. But she was more intense. She could have been anything. But it wouldn’t have consumed her like acting. TERRI: We shared the same room. She used to sit up at night and read and study and watching the way she went at it just scared me shitless. Nobody else in the world could’ve worked like that but watching her I got the impression that high school was something that would make or break you for life. Her birthday is on St. Patrick’s Day and one year she had a guy serenading her outside the window on Briscoe Street. That kind of stuff actually happened to her. She somehow managed to be loved by her teachers without being hated by her peers. Teachers liked her because she was bright but she didn’t play it up or hold it over you. She was interesting, funny and full of life – what seventeen or eighteen year-old guy could resist that? She was just an exciting person to be with. I remember watching her neck with her boyfriend once at the cottage. What else can I tell you? She grinds her teeth in her sleep. I remember once Mom and Dad were having an argument and I had the covers over my ears and she came over and lay on the bed with me and held me. And I remember sensing this so strongly – that it was equally for her as well as me – we were going to comfort and reassure each other. |

|

MARY JO: After two years of university in Toronto she came and told Pat she was going to England and he was just terrified. She was brilliant and she’d just quit college and announced she was going into acting. “Just get your B.A.,” he said. “And you can always teach; give you something to fall back on.” He wasn’t mad at her but he was really worried. And now there’s nobody who’s more proud of her. He always carries around a folder of articles and reviews. KATE: The last time I saw my mother, I had come from England for the summer to take care of my father who’d had a heart attack. One day I was sitting in a chair looking out the window when I felt this terrible blow. My mother had taken this great, heavy glass vase and clouted me from behind. It burst my eardrum and there was blood coming out. I shoved her back into a chair and I ran to the hospital. When I got back home, I asked my mother if she would go into a hospital. She said she would. Over the years, we had been through every clinic and hospital around, starting with the best and the fanciest, until no one else would take her except the public mental hospital. Then they came from the hospital, she changed her mind and said she wouldn’t go. She said she wanted her wallet and wouldn’t go without it. We looked all over the house and couldn’t find it. I had a wallet that looked like hers, so I said, “Here, Mom, I found it.” And she looked at me and said, “Oh, Tricia, you know me better than that.” And they took her away and that’s the last time I saw her. TERRI: When she was out at the Ontario Hospital, it took me four or five months to work up the courage to go and visit, to admit it had come to this. I was a lost soul for those years. My face was all distorted with spinal meningitis, so I couldn’t even look in a mirror. I’d pulled away from all my friends at school and just kept it all inside. My marks were terrible. I just had zero confidence in myself. So I stalled and I stalled and then I finally went out. Seeing her there was very hard to deal with because . . . she wasn’t made of that stuff. The people that were all around her were zombies and morons. It was just awful to see her in there. And of course she played that up too, that she was above all this. MARY JO: Looking back, you know, I think we were so naïve. We didn’t know other people had these problems; that it was maybe something you could treat if you acknowledged it early enough. We just didn’t know how to handle her, what her needs were. TERRI: It was always nerve-wracking when she’d come back from the hospital because your hopes would be up. You’d think, maybe things will be normal now, whatever ‘normal’ is. Or you’d be waiting for her to screw up, and then you’d think, well, that’s not being very helpful. And then you’d find the bottles and you’d know she was drinking again and things would just get worse and worse. The last time I heard her voice, she’d left us by then and come back to get some stuff before heading out somewhere else, and I was upstairs. And I didn’t even go downstairs. If Dad or Mary Jo knew where she was going, they didn’t tell me and I didn’t ask. My feelings at the time were so mixed. Her voice was always a comfort to me but the sight of her used to bother me. All her dignity was gone. That was too painful for me to confront so I stayed upstairs and just listened to her voice – not the words – just the sound and the tone. When she died . . . she was travelling around the country in a trailer, it caught fire and she was asphyxiated . . . when she died I couldn’t feel the relief, didn’t feel we’d done everything we could have. Don’t know what we could’ve done either. She’s such an enigma to me. Unlike my brother and sisters, I have a drive to find out more and they won’t tell me. I don’t even know if such a thing’s possible but I’d love to try to understand her. MARY JO: When she did finally leave she said to me, “You’ll never see me again.” And I felt really relieved when she said that. But it ended up being the truth. It was an act of love. She knew she was hurting us, she knew how hard, how impossible it had all become and she loved us enough to just go away and die. And that’s awful. But I think she knew she was going away to die. There’s a lot about the end that I don’t know, that I don’t want to know. It would probably rip me apart from the inside to know all the details. TERRI: Mary Jo won’t admit it, but she does deal with it. Her whole life is an expression of doing things the way Jay didn’t. So in essence she’s dealing with it every day of her life. JOE: Toward the end of her life my involvement with my mother was of a nature that is so repugnant and so negative that I don’t even speak of it. My sisters don’t even know the situations I was called out on various occasions to confront. I’m the only one who saw her in the absolute last months of her decline. In those months I was dealing with an individual whom I didn’t even recognize and to whom I had no relationship whatever. I’m the only one, the last one in our family to see her alive and I’m the only one that ever saw her dead. And when the end came, I must confess, I had an enormous sense of relief. At last, she’s at peace. Memory, of course, is selective, but I had the best years of her life. And this is why Kate is so terrified of London. This one-dimensional thinking that would dump on Jay or play her up as a scandal, a skeleton in the closet. When she’s no such thing at all. All of us revere her memory and thank God that we had her influence in our lives. You’ve got to see her all in all. This domineering, assertive, aggressive individual who later self-destructed – she’s the obvious villain in the piece. She doesn’t look good. But she was. She had beauty and excitement. Everyone who knew her was thrilled and challenged by her. You can’t have a great tragedy unless you’ve had the ability, the potential for great achievement. It’s nothing if a loser loses. But when someone with so much force, energy, potential blows it or it all slips away or those same great energies turn destructive – that’s the stuff of tragedy. |

|

KATE: It didn’t occur to me why I was doing this play when I took it. [Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten] I thought I ought to do something big after Plenty. Do a classic. Show my range. And then we started rehearsing and I was in the room with that, that thing, and I realized, my God, this is why I’ve done it. I wasn’t there when my mother died and when I play these scenes, I send my forgiveness to her. I am tortured every night. I shed real tears every night. There’s an awful lot that resonated in this play. The last two lines of the play – “May you have your wish and die in your sleep soon, Jim, darling. May you rest forever in forgiveness and peace” – every night I send those out into the air for my mother.

TERRI: It’s harder for me to take in the movies than to see her on stage. Movies are so big and intense and total and when I sense her acting is off, that some scene isn’t ringing true – it can be awful. But I know I’m her worst critic. The emotions she has up there are honest ones, I recognize them as Tricia’s and it can be very hard to see past that to the character she’s supposed to be playing. So far the theatrical roles have been much deeper and allowed her a greater range. When it comes to movies and getting the right scripts, who-do-you-know and all that junk, she hasn’t played the game well. MARY JO: She’s getting scripts all the time but she’s so fussy about what she’ll do. I read the scripts at the cottage and I go, “C’mon, Trish, this one’s kind of cute.” But she’d rather starve than do something stupid. I don’t understand what the criteria is. JOE: You’re right, we have a great deal of use for each other, especially in these last eight or ten years with Mother’s death, Kate’s achievement and the discipline that forced on her to isolate and consolidate the people she knew best, the people she can trust. Because of celebrity you have to be very careful about the people you let into your life. Then I became ill about eight years ago, have been chronically and episodically ill with my lungs, with surgery, and now with a disease of tumours and lesions in my intestines. And illness, that brings you together. TERRI: Mary Jo’s house is the nerve centre now. Grand Central Station. On the rare occasions when Trish ducks into town, she hides out there and usually manages to get ill for a while. But Mary Jo, Trish and Jan are always phoning each other up so it’s Mary Jo who knows what everybody is up to. I’m there on my day off, Joe’s in once a week and Mary Jo hosts Christmas now. She’s the normal family we all never had. MARY JO: Pat comes every day for lunch and he brings a sandwich for Martha and a sandwich for Mary and it doesn’t matter what kind they are, they’ll eat them because they come from Gramps. He could put Puss ‘n Boots in them and they’d say, “Geez, Grampa, these are great!” Then they go through and watch The Flintstones and Terri and I, we’re back to the caves. We know them all by heart. We just have to hear ten seconds and then, “Which one is it, Mary Jo?” If the kids start fighting or there’s any other thing Pat just does not want to deal with, then it’s, “All right, pack it up.” KATE: When I was growing up, my father was the most powerful source of hope I had. The events of Jay’s life were so dramatic, so volcanic, that she’s the one we always seem obsessed with. But Pat’s love was so important to all of us that I’d hate to see his influence overshadowed or diminished by the amount of attention which, understandably, we’ve all had to give to Jay. He was quieter, steadier, stronger. He was all those things that are so much easier for outsiders to overlook but he was of essential importance to us then as he still is today. JOE: There’s no stone on Jay’s grave at the cemetery. There’s nothing there at all and that’s as it should be. Let the monument be in the lives you’ve affected and please God, I never misjudge her, never presume to her motives. Where is Jay’s influence now? It’s going to appear in a movie this fall. It’s on Broadway and the London stage. It’s in some little kids in Toronto and London. It’s in some churches in Mt. Carmel and San Diego. It’s in some students who really listened when she taught. August 1985 |