|

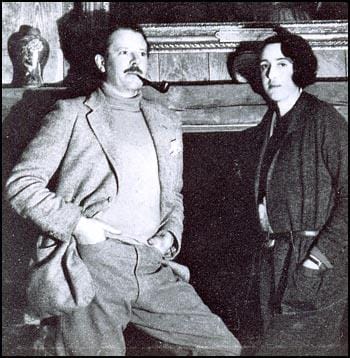

AN UNCONVENTIONAL MARRIAGE WORTHY OF AFFIRMATION MATRIMONIALLY SPEAKING, this is a bewildering time. On the one hand, we are asked – indeed hectored and not so subtly commanded – to consider as marriageable couples who 20 years ago would not have been regarded as biologically qualified for the position. On the other hand, a large proportion of young couples of all orientations don’t see the point of marriage at all and blithely forgo it altogether without censure or reprobation (except perhaps from their traditionalist elders whose concerns are of little account). So there is pressure for all of us to vocally affirm a simultaneously expanded and watered down definition of an ancient institution but there is no attendant sense of compulsion – even after the birth or the adoption or the medically assisted concoction of children – to actually participate in it one’s self. I’m frankly skeptical of the whole discussion and reserve my marital affirmations for unions I know something about. One of the most exotic and wildly unorthodox of these was that which joined English author, journalist, diplomat, parliamentarian and homosexual Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) with poet, author and lesbian, Vita Sackville West (1892-1962). They tied the knot on October 1st, 1913, knowing full well that they were sexually incompatible and would not be faithful to each other in the usual sense. But they did love each other deeply, wanted children and rose at least three times to the challenge of conceiving new life. One child was stillborn but two sons survived. The youngest of these, Nigel (half owner of Weidenfeld & Nicolson publishers) characterizes his parents as “sexual strangers to each other after the birth of their sons.” Harold was a child of the middle class and nobody’s idea of a hunk. He was outgoing, insightful and considerate about others, patient, hard-working and dependable. Vita was born into money and stunningly beautiful (though in some photos there’s a suggestion of horsiness). She was the daughter of idle and dysfunctional snobs, impetuous and intuitive and inclined to reclusiveness when she wasn’t being consumed by passion for her latest love object. Vita’s appetite for dalliances far outstripped Harold’s. Her famous fling with Virginia Woolf was easily contained within the unconventional terms of their custom-designed marriage. It was an earlier passion for Violet Trefusis which drew her perilously close to throwing over her marriage and walking out on her children. But luckily for Harold who didn’t mind what kind of shenanigans she got up to so long as she remained committed to him and the children, her friendships and affairs tended to burn out quickly. A few years after the Trefusis affair had run its course, Harold shrewdly noted in his diary: “I have got into the way of taking my happiness for granted. Yet Vita is not a person one can take for granted. She really does not care for the domestic affections. She would like life to be conducted on a series of grande passions. Or she thinks she would. In practice, had I been a passionate man, I should have suffered tortures of jealousy on her behalf, have made endless scenes, and we should now have separated, I living in Montevideo as H.M. Minister and she breeding Samoyeds in the Gobi Desert.” Other than their children, their greatest joint project was the spectacular garden they created together at their restored country estate of Sissinghurst – a major draw for tourists and horticulturalists to this day. Nigel sees in their different contributions to that enterprise a reflection of his parents’ symbiotic relationship: “His are the firm lines, the symmetrical placing of urns and statues, the broad steps and paths, the vistas; hers the overflowing vines, figs, roses and clematis.” Vita was highly esteemed as a poet and a writer in her day but few make large claims for her anymore. Her most lasting contribution to literature may turn out to be her attractiveness as a subject for tell-all biographies and picture books with lots of photos of her home and garden. Harold’s literary ambitions were more modest and most of the books he steadily cranked out – biographies, travel books, social and political surveys – are also forgotten today. Because of his great political connections in 1949 he got the commission to write the ‘official’ biography of King George V. It would turn out to be a huge money-spinner but a couple of snippets from his diaries while he struggled with the book’s composition explain why most of his books are so unappealing today: “I start writing the first chapter . . . I begin ‘Prince George was born at Marlborough House, London, at 1:30 a.m. on the morning of June 3, 1865.’ I gaze at the sentence in wonder, realizing what a long journey I have to go before I reach his death. It is like starting in a taxi on the way to Vladivostok.” Then, one month later: “I fear I am getting rather down on George V just now. He is all right as a gay young midshipman. He may be all right as a wise old King. But the intervening period when he was Duke of York, just shooting at Sandringham, is hard to manage or swallow. For seventeen years in fact he did nothing at all but kill animals and stick in stamps.” Late in Harold’s life Nigel persuaded his father to let him publish three volumes of his diaries. They outsold everything he had written before and established him as one of the supreme diarists of the 20th century. “It is sad to think that of my forty books the only ones that will be remembered are the three I didn’t realize I’d written,” he commented to his son. In addition to providing his own wonderful take on a most unconventional life, Harold’s more public work as a diplomat and MP gave him a front row seat at the Paris peace conference of 1919, in Winston Churchill’s WWII government and at the Nuremburg Trials. His peerless bohemian credentials put him in contact with many major writers and artists of his time. Here he describes his audience with James Joyce: “Joyce glided in. It was evident that he had just been shaving. He was very spruce and nervous and natty. Great rings upon little twitching fingers. Huge concave glasses which flicked reflections of lights as he moved his head like a bird, turning it with that definite insistence to the speaker as blind people do . . . One has the feeling that he is surrounded with a group of worshippers and that he has little contact with reality . . . My impression . . . was of a very nervous and refined animal – a gazelle in a drawing room.” And on top of all that, he was a benevolent genius of a parent. Let me leave you with a note he zipped off to Nigel when he was going through a rough patch: “Darling Niggs, whatever disasters may happen to you, there is always a sure haven for you in the love that Mummy and I bear towards you, and although neither of us will ever intrude upon your private life, you know that all your pleasures are our delight and all your pains our sorrow . . . there is always one spot on earth where you will always be loved and cherished, and where your interests and adventures are welcomed and shared.” Herman Goodden / The London Yodeller / July 23, 2015 / 3.15 |