|

A SHORT HISTORY OF

LONDON'S GRAND THEATRE (A talk delivered at the London Public Library on September 18, 2017) THE GRAND THEATRE has been the primary theatrical venue of London Ontario for 136 richly storied years and I’ve been told I have 35 . . . 40 minutes tops, to fill you in on its history. So by necessity this is going to be a decidedly skeletal survey of milestones in the Grand’s development with occasional glances at highlights and catastrophes along the way. A little background to set the scene. The first plays were produced in London in 1838 – 43 years before the first Grand Opera House opened its doors. Mostly farces and melodramas – were put on by British military officers of the 32nd Regiment of Foot then stationed at the Victoria Park Garrison. Posted here to fend off anticipated raids that never really materialized, these educated and cultured men turned to other pursuits to keep themselves occupied – most notably concerts and theatricals – to which civilians were also invited and which were promoted and reviewed in London’s early newspapers. |

|

By 1844 the first civilian troupes started mounting their own productions in barely converted barns and chapels and hotel meeting rooms and in 1873, London’s first professional troupe, the family-run Holman Opera Company relocated to their patriarch’s home town and played out the last decade of their remarkable 30 year career from their own theatre in a refurbished racquetball court at the northwest corner of Richmond and York.

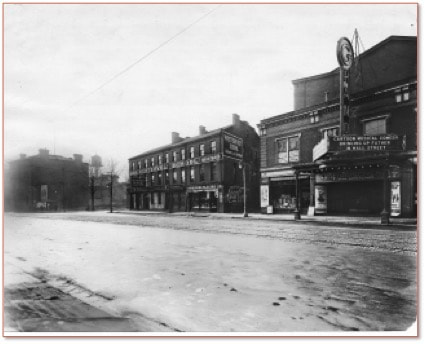

C.J. Whitney was a Detroit-based lumber baron who constructed his first theatre in Detroit in 1875 and quickly built up his own independent chain of theatres which included Opera Houses in Toledo, Ann Arbor and Battle Creek. In the later half of the 1870s, Whitney also had an agreement to manage the Holman Opera House when the family troupe was out on the road for the better part of each year playing all over Ontario, Quebec and the Northeastern United States. With the closing of the Holman Opera House in 1881, Whitney signed a lease to become sole operator and manager of London’s Grand Opera House which was to be built one block north of the Holman site on the northwest corner of King and Richmond Streets as part of the massive new Masonic Temple. |

|

London’s Grand Opera House thus became the first Canadian link in Whitney’s chain of theatres. And as his holdings kept expanding over the next dozen years, Whitney very profitably booked touring shows and acts into any or all of the nearly two dozen theatres he controlled in Michigan, Ohio and Ontario. Until his death in 1903, Whitney remained a large and powerful player in the theatrical touring world and London’s key position between (and its rail linkage with) such major centres as New York and Chicago, ensured that there weren’t many shows London didn’t get to see.

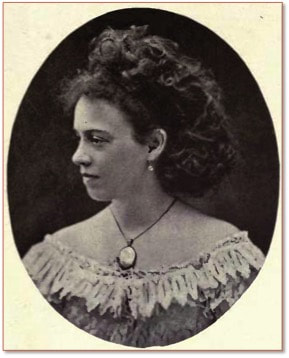

The construction of a new theatre space could provide months’ worth of fodder for London’s newspaper columnists as they drummed up interest for opening day. While earlier theatres were the improvised playhouses of bored soldiers and impecunious bohemians – with little concern for such notions as the comfort of their patrons or turning a profit – the Grand Opera House was an altogether more imposing enterprise. The construction of this ‘Second Empire’ temple of culture right next door to London’s City Hall marked a level of middle class acceptance and respectability that would have astonished the officer/thespians of the Garrison. Constructed at a cost of $85,000, once The Grand Opera House was fully operational in September of 1881, it became apparent that theatre in London had entered a slick and hard-nosed phase. The Grand was a play factory, designed to keep the shows turning over and the crowds pouring in, and over the next 20 years, this one theatre would host up to 300 performances annually; plays that were cooked up and sent out on the road by as many as a hundred different American, British or Canadian production companies. One of the big names (though little remembered today) who toured here in the Grand’s earliest years did at least make a real connection with the London area. The Brooklyn-born Annie Pixley first appeared at the Grand in 1882 in her phenomenally popular musical adaptation of Bret Harte’s short story The Luck of Roaring Camp. Pixley’s annual summer sojourns to the Fraser House Hotel in Port Stanley – with her family and dozens of fellow actors and admirers in tow – first put Port Stanley on the map as a resort. Henry Irving and Ellen Terry played the Grand in 1884. Lily Langtry, or ‘the Jersey Lily’ made her first Forest City appearance in 1887. Audiences were wowed and press reports were respectful but when she came back in 1903, the bloom was off the lily and the gloves were off the critics. One press review by E.J. Carty in The London Advertiser called her everything but a royal slut. Similarly Sarah Bernhardt’s first appearance at the Grand in 1896 received great promotional press and reviews. An enormous crowd gathered at the GTR station as the Divine Sarah’s specially outfitted coach pulled in from Toronto and that crowd patiently waited a full hour for the legendary actress to actually step out into the open air and greet her fans. But for her return visit in 1910, there was no comparable public reception and the critics were far less indulgent, with the London Free Press chiding her for a performance that misfired and panning her portrayal of Joan of Arc on the grounds that, “The famous actress is too old to create an illusion of youth.” London critics of the time seemed far less inclined to attack eminent male actors. The rapturous reception repeatedly given the now forgotten Thomas W. Keene by London audiences and critics was typical of secondary theatre markets throughout North America where his florid, scenery-chewing antics always went down a treat. Early in the morning of Friday, February 23rd, 1900, that first Grand Opera House caught fire. Three days later, Colonel Whitney’s son announced that his father had been planning for a while to build a new and improved Grand Opera House and this fire was the spur they needed to put that plan into action. |

|

After putting on shows for a year and a half in temporary quarters at The Mechanics Institute (including a well-attended talk by a young Winston Churchill recalling his sensational escape from his Boer War captors), the new Grand Opera House opened on September 9, 1901 (20 years and one day after the opening of the first Grand) at its current location three and a half blocks north on Richmond Street.

With seating for 1,850 patrons, it instantly became one of the largest theatres in Ontario, although the building didn’t look like much from the outside. One Free Press writer went so far as to say the building “has the appearance of a car barn with cold storage at the rear.” Nor was there much grace to spare in the lobby or the theatre’s entranceway. But once inside the theatre’s auditorium, the impression was very different. Even the same writer quoted above agreed, “the playhouse has a magnificent interior.” Part of the reason the back of the building was so high was the presence of a second gallery or balcony called “the gods”; so named because of the godlike perspective on everything happening below. The sumptuous atmosphere throughout the auditorium was crowned by the splendid mural on the proscenium arch by Toronto artist Frederick Sponton Challener who accepted a number of mural commissions for theatres in Whitney’s chain from his co-manager, Ambrose J. Small. With 1,890 square feet of acting space, the Grand boasted the largest stage in the entire dominion. On the stage that opening night was the Manhattan-based William Brady Company’s popular production of Lottie Blair Parker’s Way Down East, a ‘country-virtues-versus-big-city corruption’ melodrama in four interminable acts. In the play’s climactic scene when the long-suffering heroine is driven out into a howling blizzard by the sadistic Squire Bartlett, the stage was awash in blue-shaded footlights and electric fans blew buckets and buckets of swirling soapflake snow all around the stumbling, shivering heroine. Colonel Whitney boasted to the press on opening night, “And now with the equipment here, with the magnificent stage, we shall have no trouble in having all first-class companies stop over at London.” Home grown productions were not on the Colonel’s radar. As Sheila Johnston notes in her 2001 history of the Grand: “The new theatre did not include any rehearsal halls, workshops or large storage areas because London’s New Grand Opera House was not meant to accommodate a producing theatre company. Its sole purpose was to showcase prepackaged shows that originated elsewhere.” |

|

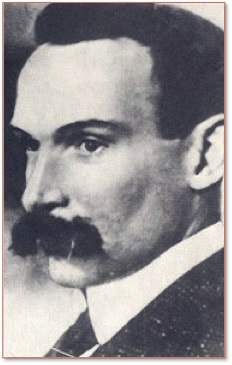

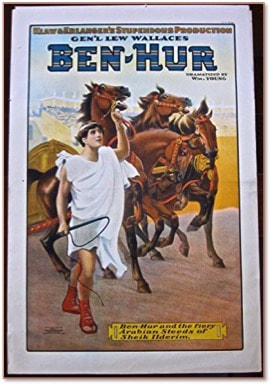

Within two years of the Grand’s reopening, Colonel Whitney was dead and his partner Ambrose J. Small bought him out. With the passing of Whitney, and a couple years later the retirement of William Bennett who ran a vaudeville operation in the old Mechanic’s Institute, Ambrose Small suddenly had the professional theatrical field to himself in London. No single show of Small’s regime more effectively caught the public’s fancy, selling out every performance and winning deliriously ecstatic reviews, than the gargantuan production of Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur, adapted for the stage by William Young. On March 21st, 1910, we find this preview blurb in The London Advertiser:

“One would imagine from the amount of paraphernalia that reached London Sunday . . . that it was a circus coming to the city. . . Eight 60 foot cars arrived containing baggage, etc of the “Ben-Hur” Company. Included are 15 horses and one camel . . . By ten o’clock some 30 loads of scenery were removed from the cars. This, including seven cars of stage scenery that arrived last Tuesday, makes this the largest theatrical production that has ever arrived in London.” |

|

Big names continued to play the Grand such as Ethel Barrymore, Marie Dressler, the Russian ballerina Pavlova and the Scottish singer Harry Lauder. Much-loved London English teacher Louise Wyatt remembered being taken to the Grand in 1914 when Commander Evans presented an illustrated lecture about his participation in the doomed Antarctic expedition of Captain Scott. But overall the years of the First World War were hard on professional touring houses across the country and the Grand, like many other such theatres, started to augment its bill of fare by running motion pictures.

It was just as that war was finally winding up that Ambrose Small decided to sell off all of his theatrical holdings, including London’s Grand and other theatres in Toronto, Hamilton, Peterborough, Kingston and Ottawa, for $1,750,000, to the Trans-Canada Theatres chain. Also included in this sale were Small’s booking contracts for a dozen other Ontario theatres. After depositing a cheque which covered the first installment of his buyout for one million dollars in a Toronto Bank on December 2nd, 1919, Ambrose Small disappeared from the face of the Earth, presenting professional and armchair detectives with a mystery that is still unsolved. The Grand is still said to be haunted by Ambrose Small’s ghost though it’s been a few years since I’ve heard of a sighting. One of the more prevalent theories is that his body was disposed of in the Grand’s coal-fired furnace. While he did nothing for the development of indigenous theatre and rarely presented his audiences with anything that wasn’t a proven, sure-fire money-spinner, Ambrose Small routinely brought to all his theatres the very biggest American and British shows and stars which his audiences most wanted to see. A lot can be said in criticism of that accomplishment – in the same way that many thoughtful people are concerned today at how the American media dominates and suffocates Canadian cultural life – but for good or ill, nobody has ever equalled Small’s knack for booking the biggest sensations and packing in the audiences. The Trans-Canada Theatre chain only operated the Grand for four undistinguished years before selling it off to Famous Players Theatres, one of the first of the big movie house chains, which immediately ripped out the second balcony to better outfit the theatre for the projection of movies. With the rise of movies and radio, the number of touring companies that still found it profitable to take their shows out on the road had plummeted. Whereas in 1900 there were about 340 such companies offering their wares to the Grand, by 1920 that number was down to 39. The whole raison d’etre of the place was changing, reflected in its advertisements in which the ‘Opera House’ was redubbed ‘The Home of Features’ and ‘The Home of Amusements’ before eventually settling on The Grand Theatre in the 1930s. Realizing that they had to put something on the boards, in the 1925/26 season, John Minhinnick, long-time manager of the Grand, desperately assumed the role of producer for the Grand Theatre’s own in-house stock company which struggled to present a different play each week; a pretty uneven outfit from all accounts, sometimes winning grudgingly respectful reviews and other times letting the curtain go up on shambolic performances where the actors weren’t even ‘off book,’ lurching about the stage in under-rehearsed disarray and reading their lines from scripts in their hands. |

|

But mostly the Grand had become a movie house and would periodically rent out their facilities to a series of local amateur companies that included the London Drama League, the Half-Way House Players, the Meredith Players and the Community Drama Guild. And in 1934 these four groups threw in their lot together under the leadership of McCormick’s Biscuits heiress Catharine Brickenden, and formed the London Little Theatre which then leased the Grand for $2,100 a year as their base of operations. To raise money for this venture, they concocted a little scheme that continues to serve the Grand well to this day – an upfront subscription which amassed funds from nearly 800 patrons as they headed into their first season.

In their second season an LLT production of Twenty Five Cents, a newly written drama about a family struggling to get by in the Depression by Sarnia-based writer W. Eric Harris won all the major prizes for acting, direction and script as well as Best Show in the third edition of the Dominion Drama Festival - the first time that top prize had been awarded to a Canadian script. Getting a sense of how theatre could reflect a community, the 38/39 season saw the first full-length play by a London author on a London subject when LLT produced a script by Hilda Mary Hooke, based on the life of the colonial officer most responsible for the settlement of London, Colonel Thomas Talbot. Its preposterous title of Here Will I Nest was sensibly changed to Talbot of Canada when pioneering filmmaker Mel Turner adapted the script for his full-colour movie starring many actors from the LLT. |

|

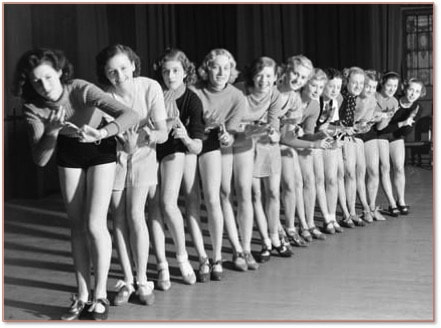

Whereas the First World War caused the old Grand Theatre to pull in its wings, World War II was an expansive period for LLT. Under the auspices of the Citizens Auxiliary War Services Committee, a special company was assembled for the purpose of taking locally produced shows out to military training bases within an 80 mile radius of London. The troop show which ultimately went through 12 different ‘editions’ was called Take It Or Leave It and was built around song and dance routines and original skits all put together by LLT members. Performed at least once a week from October to May during every year of the war, the 50 people in the company prided themselves on being able to send up the curtain on their show 30 minutes after disembarking the buses at whatever training base they were visiting that night. Dancing showgirls in skimpy costumes were no small part of the attraction, particularly one crackerjack sextet who called themselves The Rhythmettes. When I interviewed LLT stalwart Mary Ashwell in the early 90s, she told me those were some of the most appreciative audiences she ever played to where an awful lot of corny humour would be forgiven, so long as the boys “got to see a little leg.”

It was also during the war that LLT started up – often off-site in smaller venues - the Studio Club for mounting children’s shows, Christmas pantomimes, and edgier, more experimental fare and local scripts. This tradition continues today in the McManus Studio. In May of 1945 a major challenge was dropped into LLT’s lap. Famous Players had received an offer to buy the Grand for $45,000 from a firm of bowling alley operators. Catherine Brickenden put the pressure on Famous Players’ president when she met him at a horse show in Toronto and he generously agreed that LLT could have the Grand for $35,000 provided they closed the deal within one month. Through some heroic fundraising, this they were able to do and three years later they had paid off their mortgage as well. |

|

London Little Theatre was now recognized as the biggest little theatre in the country. For their 46/47 season they received special permission to present the first non-professional production of Agatha Christie’s mystery thriller, Ten Little Indians. The next season LLT hosted the opening night performance of the John Gielgud Company’s touring production of The Importance of Being Earnest, starring Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford (as Lady Bracknell, of course) and Pamela Brown. The LLT’s welcoming party overwhelmed their war and ration-wearied guests with gifts of fruit baskets, nylon stockings and American swing records. But even so, Margaret Rutherford was so overwhelmed with the abundance in Canadian shops that she almost missed her third act cue in a matinee performance as she had ducked out to Kingsmill’s during the interval and lost all track of time, being hauled back to the Grand by flustered house manager Ken Baskette and having to complete her performance in her decidedly non-Edwardian street clothes.

|

|

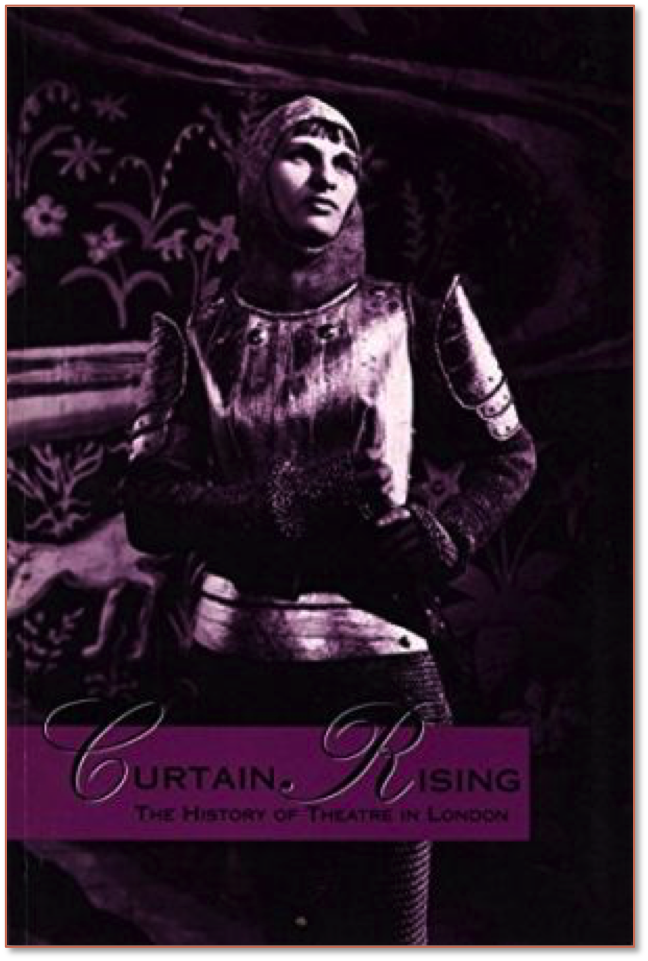

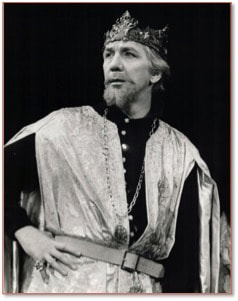

Over the next couple of seasons, LLT hit its high water mark artistically and commercially. In May of 1948 a production of George Bernard Shaw’s St. Joan starring Olga Landiak won every prize worth having at that year’s Dominion Drama Festival in Ottawa where Landiak, in costume, was immortalized in a stunning photograph by Yousuf Karsh. Going into the next season LLT’s subscription base peaked at 10,000. As London’s population then was 91,000, more than one in ten Londoners was a supporter.

By 1950 there were burblings by a few souls in the LLT executive that it was time to go professional. The Shelton-Amos Company from New York had presented the first of six seasons at the Grand presenting summer stock and had been wildly successful. By 1953 the fully professional Stratford Shakespearean Festival was underway just 45 miles up the highway. In a 1984 article in Encounter magazine, Alice Gibb dug up a report submitted to the membership by the LLT executive that said, “It is the belief of the executive that Londoners wouldn’t be sympathetic toward a professional, profit-making company with a salaried personnel.” Seven years later with subscriptions falling, community interest dimming and LLT energy and morale draining away, a half measure was introduced. The company would hire its first ever artistic director but carry on otherwise as an amateur troupe. |

|

The British-born and classically educated Peter Dearing who worked as artistic director from 1957 until 1968, struggled heroically to make this compromise work and unquestionably improved the quality of presentations. He kicked off his directorship with a big glitzy musical – South Pacific – the first musical and biggest production yet mounted by LLT and it was indeed a smasheroo. Dearing-directed musicals became a highlight of every subsequent season. In another shrewd bid to sell tickets, Dearing planted at least one play in each season which was then being studied in London high schools – Macbeth, Inherit the Wind, Caesar & Cleopatra, etc. – and thus filled up the seats with English and drama classes on field trips. But the shows that brought the awards and trophies home to London were the modernistic, edgy plays like Six Characters in Search of an Author (1960) I Am a Camera (1962), Mother Courage (1965) and Marat Sade (1968). Nearly all of these were personally directed by Dearing as well.

When Dearing’s bid to augment the casts of each show with three or four core professionals was rejected, he tendered his resignation. Over the next three years miscellaneous professionals were hired to direct amateur casts on a per-show basis. But with no one at the helm to give the ship direction, the theatre was floundering, the playlists were uninspired (Your Own Thing, A Flea In Her Ear, Star Spangled Girl – these are not plays to be conjured with), subscriptions fell to almost half of what they’d been 20 years earlier and LLT started to take on debt. And so at the annual general meeting of 1971, LLT finally bit the bullet and voted themselves out of existence. As long as they retained their amateur status, they were ineligible for operating grants from the Ontario or Canada Arts Councils. A year before, the Dominion Drama Festival had also closed up shop, another sure sign that the age of the amateur was over. Still, many LLT members who had spent half their lives working on productions for the sheer love of it were reluctant to admit the time of day. Then the same Catharine Brickenden who had been so instrumental in bringing the LLT together and buying their own home, turned the tide of opinion one last time by announcing, “It’s time we bade farewell to London Little Theatre.” |

|

Heinar Piller came on as artistic director in 1971 with a three year plan to turn the newly dubbed Theatre London professional. Particularly during his first season, he had to contend with the hurt feelings of the old LLT community. Some of those amateurs still held seats on the Grand’s new board of directors and others showed up for auditions where the best they could now expect were supporting roles, working under actors who were being paid to do what the LLTers had always done for free.

Piller mixed things up as best he could, slotting in guaranteed crowd pleasers like Charley’s Aunt and Man of La Mancha next to more challenging productions like George Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe and Orlo Miller’s London history play, Cronyn. Piller’s commitment to Canadian fare was pronounced (and Canadian plays were being written like never before) and generally well accepted until a late offering in the 74/75 season of Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. On opening night, after Wayne Burnett as Billy bellowed the words, “I’ve been fucked by Christ!” - 60 patrons either fled right away or didn’t hang around for the second act. This one production was also responsible for 2,000 cancelled subscriptions – a full third of Theatre London’s much-needed base support. |

|

Next up the first of the Stratfordians, William Hutt, took over as artistic director in 1976. As one of the most revered figures in Canadian theatre, Hutt was able to call on a pool of Stratford Festival-based actors, directors and even crews to help out with productions of such classical fare as Candide, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Private Lives and Schools for Wives – and those were all in his first season. While there was some grumbling about Hutt turning Theatre London into an ‘annex’ or ‘fourth stage’ for Stratford, there was a far more sizable and influential audience who’d been alienated by the experimentation of the Piller regime and they started to come back in droves. And this was all for the good because in the very next year Theatre London was going to need all the friends and all the support it could get.

For the 77/78 season, the Grand Theatre wasn’t just dark, it was largely demolished. Before the long-required 5.5 million dollar overhaul got underway, all that remained of the old theatre were the three back walls of the main stage area and the proscenium arch. A new roof was put on, a new heating and ventilation system was installed, and the front of house was completely reconfigured and expanded into three spacious storeys with new lobbies, offices, rehearsal and storage spaces, a bar and a crackerjack in-house studio theatre in the basement called The McManus. The 78-79 season didn’t get underway until late November in its snazzy new digs with a Hutt-directed production of Kiss Me Kate that featured the never more appropriate Cole Porter song, Another Opening, Another Show. |

|

Another Stratfordian, Bernard Hopkins, took over Theatre London’s reins from 1980-83. While he wasn’t here for a long time, he did a notable job of connecting with the London community, particularly its writers. He featured Alan Stratton’s Nurse Jane Goes to Hawaii and James Reaney’s Antler River on the big main stage, and downstairs he starred in two scripts by Ric Wellwood, as Truman Capote in Sting Like a Butterfly, and as Napoleon during his years of forced isolation on Elba in Exile.

After a 12 year run, the name Theatre London was retired and replaced by The Grand Theatre Company as the third Stratfordian in a row, the big kahuna himself, Robin Phillips, commenced his one season term (it was supposed to be at least three) as the Grand’s new artistic director. His ambitions were gargantuan and splendid but they paid no heed to the Grand Theatre’s history and traditions, they absurdly assumed a level of enthusiastic support that never materialized and they just about decimated the place, racking up a nearly two million dollar debt in six months flat that would take years to get clear of. |

|

Phillips assembled a repertory company. Instead of hiring actors on a per-play basis, he assembled a permanent company of 40 players - a dream team that included William Hutt, Martha Henry, John Neville, Brent Carver, Sheila McCarthy, Rod Beattie, Susan Wright, Peter Donaldson. It seemed the Stratford Festival’s constellation of summertime stars had found themselves a nearby home for the winter months. Newly constituted pay television and cable operations were supposed to make films and special programs of Grand Company fare until they started undergoing their own fiscal emergencies and either scaled back their operations or went bankrupt. Phillips increased the number of mainstage productions by 50% and more than doubled the number of presentations.

Many of London’s most dedicated theatre supporters, accustomed to decades of the subscription system, couldn’t get on board with the new routine where one had to contact the box office and specifically order tickets for each production. Adding to their disorientation was a repertory-style calendar which offered three or four plays in the same week, instead of the old system where plays were offered at the rate of one a month. Matters weren’t helped when the promotion budget for the entire season was blown by the end of December. Although attendance at the Grand did increase slightly from the previous season – small wonder considering how many more productions and performances there were – figures weren’t nearly as high as Phillips or the board were counting on. That April as everything was coming unglued at the Grand, I was hosting a reading in London by Timothy Findley whose novel, The Wars, had just been made into a film, directed by Phillips and starring Brent Carver and Martha Henry. Meeting Findley in the lobby of the Park Lane Hotel, the first words out of his mouth were a lamentation for London’s shabby treatment of Phillips: “Does this town have any idea what it’s doing? Does it expect a profit from the very first day? Things like this take time and vision and commitment. London will never live this down.” Certainly passing the artistic directorship over to Phillips’ right hand man, Don Shipley (our fourth Stratfordian in a row) for the next two years of drastically reduced production didn’t help anybody live down the disaster of the Phillips experiment. When Shipley packed in his short and thankless term, in which he only managed to ratchet up the Grand’s debt by another half million, the board undertook a far more rigorous search and lucked out with their choice of Larry Lillo, co-founder of Vancouver’s Tamahnous Theatre. |

|

As a veteran of the alternative theatre scene where shoe string budgets are the only kind there are, Lillo knew the trick of making every penny sing and dance – of cutting just those corners the audience would never see. No play in his first season had more than four actors but the sets and costumes were all first rate. When a few grants from Wintario and the Ministry of Culture were added to the half million dollar surplus Lillo realized that first season, the accumulated deficit was entirely cleared. In his second and final season (he left to take over the job he’d always wanted as artistic director of the Vancouver Playhouse) he was able to expand his theatrical palette and put on two of the most brilliant productions I’ve ever seen anywhere – George Walker’s Filthy Rich and Caryll Churchill’s Top Girls.

|

|

Lillo had directed Top Girls and Filthy Rich was directed by the Grand’s next artistic director – and fifth Stratfordian – Martha Henry, who stayed at the helm for seven years. She was with us long enough to develop a sound sense of what plays well in London but never just capitulated to popular taste; always insisting on tossing more challenging fare into the mix. She presented three A.R. Gurney scripts during her reign – The Cocktail Hour, The Dining Room, Love Letters – and they went down as smooth as could be; but also two David Mamets – Glengarry Glenn Ross (which ticked off more subscribers than any play since Billy the Kid) and Oleanna – which frankly stuck in a lot of Londoners’ craws. She once shared this theory about how far she could push the envelope: “Initially I felt that as long as I thought a play was good and whole and written with integrity and a skilled pen, that it could stand on a stage anywhere . . . I’m beginning to realize that I have to be very careful how I put some plays in front of my audience. What I found was that if a subscriber didn’t like one show, they’d complain. If they didn`t like two, they would think seriously about re-subscribing. And if they didn`t like three, forget it.”

She obviously gauged all this pretty shrewdly because at the start of her 1989 season, the Grand set an all-time record of 14,575 subscribers. And her domestic arrangements meant that whenever she needed to dig her way out of a hole, she could always bring in her partner Rod Beattie to put on one of his perennially popular Wingfield plays. |

|

The four season term of Michael Shamata, brought in from Theatre New Brunswick, seems to be remembered most for its clunkers. In the first season he foisted his own adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula on us (a remarkably leaden ‘retelling’ as opposed to a ‘reshowing’) and then there was the second season’s preposterous production of Maureen Hunter’s Atlantis. Nobody who saw Atlantis remembers the story or even the acting; just the fact that the entire stage was covered in seven inches of water – some 4,000 gallons – that was kept at room temperature to prevent Tanja Jacobs and Benedict Campbell from breaking out in chilblains as they sloshed around for two soporific acts and made every patron feel like they’d spent an evening at the sauna.

By the end of Shamata’s directorship, the Grand was once again saddled with a hefty operating deficit of $1,300,000. However on the plus side, in his last two seasons he did introduce The High School Project, which has been maintained and expanded in ensuing years. This innovative program invites high school students from across the city, on stage and backstage, to work with professionals in mounting full productions – often musicals – that crackle and fizz with intoxicating energy. These shows link up our theatre with the community in a very dynamic way. And with all those relatives who are compelled to buy a ticket and see what their young people are up to, they do fabulous business. |

|

Kelly Henderek’s short two year term as artistic director was distinguished by his determination to include as many London artists as he could in Grand Theatre productions. Could he perhaps have been thinking of London actress Kate Nelligan who never appeared on a Grand Theatre stage when he told The London Free Press, “We don’t want them leaving here and saying later that they never played here”? In addition to giving work to London actors, directors, musicians and set and lighting designers, in his second season two plays by London-raised authors were featured on the main stage – Greg Nelson’s North and Allan Stratton’s The Phoenix Lottery.

The curtain went up on Susan Ferley’s artistic directorship in the dark month of September, 2001 which also happened to be the 100th anniversary of the Grand Theatre’s opening in its current location. Her phenomenal 15-year run as artistic director is unparalleled in the history of the Grand. Thanks to a fund-raising blitz headed up by Don Smith and increased annual support from the City of London, Ferley and the theatre’s canny executive director Deb Harvey, were able to retire the Grand’s accumulated deficit of one million dollars and post 15 successive surpluses. |

|

In addition to running a tight fiscal ship, Ferley doubled down on her two immediate predecessors’ commitments to get more Londoners involved in the Grand. She expanded the High School Project and directed their mainstage show each year. She founded the Playwrights Cabaret showcasing new works by local writers, came up with a High School Playwrights Cabaret for student writers and also inaugurated The Grand Academy, a week-long intensive course in musical theatre that is offered twice a year. And she also put together all those beautifully balanced seasons of shows, including last year’s with its heavy Canadian content in a nod to Canada’s 150 celebrations.

So even though he’s been on the job for a full year already, this season will actually be the first one when the Grand’s newest artistic director, Dennis Garnhum, will be calling all the shots. I’m looking forward to hearing where he plans to take things from here. Herman Goodden: A talk delivered at the London Public Library, September 18, 2017 |