|

BOOKS FOR THE HOPELESSLY BOOKISH

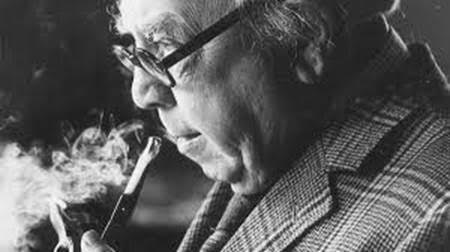

The London Yodeller (4.14) JULY 7, 2016 Hermaneutics by Herman Goodden ABOUT A HALF CENTURY AGO, a handful of British writers swam against the tides of specialization, academicism and politicization – then still rising towards the intimidating stature they’ve achieved today - and dared to produce sweeping histories or outlines that charted the overall development of literary culture. The first of these that I encountered, taking on the largest canvas of all and therefore not probing so deeply as the others, was prolific novelist and playwright J.B. Priestley’s (1894-1984) Literature and Western Man (1960); an intelligent, non-academic (the word ‘phallocentric’ doesn’t appear once) study of writers from Machiavelli, Montaigne and Cervantes to James Joyce, William Faulkner and Thomas Wolfe. There are other broad literary surveys of this kind written by such worthies as Will Durant and John Cowper Powys but what impresses me so much about Priestley’s opus is the humility and forthrightness of his approach. Published when he was 66 years old and dedicated to Tolstoy’s dictum that any truly great work of art should be assimilable by the average person, this book collects the gleanings of more than five decades of omnivorous and wide-ranging reading. Priestley may not pronounce the last word on any of his subjects but he does a wonderful job of displaying the full array of what’s out there and giving you a sense of its flavour. I first read this book in my teens and consider it an ideal road map to pass along to any young person with an affinity for reading. |

|

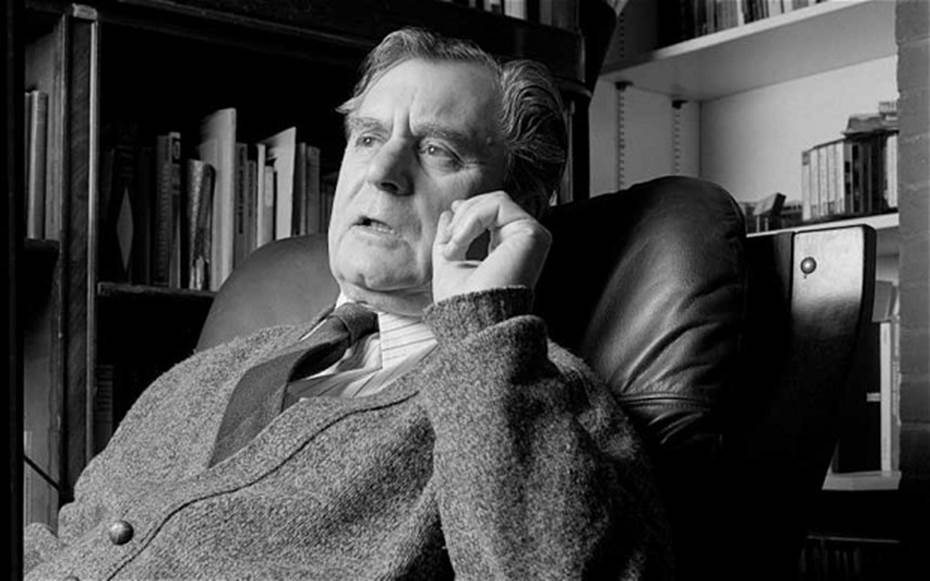

About ten years later I read Richard Hoggart’s (1918-2014) study, The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working-Class Life with Special Reference to Publications and Entertainments (1959). The only one of these generalisers with professional academic affiliation (at the University of Hull), Hoggart felt compelled to fold in some pretty arid sociological data to supposedly bolster his findings. But the engrossing, often hilarious and alternately heartwarming and appalling core of his book was his personal reflections and observations of his hard scrabble childhood in the north of England. A bright, curious and word-besotted kid, Hoggart quickly outgrew the risible literary fare that nourished his family and neighbours. He sees how the formulaic and irredeemably lowbrow novels and periodicals that flooded his house failed to challenge their readers and only reinforced understandings of the world that would keep them stuck at the very lowest rung of the socio-economic ladder. But he also has the honesty to recognize that his kin were rooted to their corner of the world and their community with a bone-deep sense of belonging and even authority that his own sophistication had stripped away and forever placed beyond his reach. By reading widely and ambitiously, Hoggart ate from the tree of knowledge and was expelled from this unlikely Eden of his early life with its cobblestones and tenements and lavatories at the bottom of the garden.

|

|

Next up was John Gross (1935-2011) whose The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters: A Study of the Idiosyncratic and the Humane in Modern Literature (1969) was given to me by my preternaturally wise friend, Jeff Cencich (who also introduced me to my main man, G.K. Chesterton, putting his Selected Essays into my hands with the words: “Check this out. I think you’ll like him.”) In this magnificent and engaging book, Gross examines nearly 200 years of developments in critical journalism, starting out with Francis Jeffrey and Sydney Smith’s launching of the hugely influential Edinburgh Review in 1802 and carrying forward to the Second World War when Cyril Connolly and T.S. Eliot were editing, respectively, Horizon and Criterion. Whatever the flaws of any of those critical journals may have been, at least they were produced by people who could write. But with the war’s end and the building boom of red brick universities throughout Britain (with their newly expanded syllabuses that included previously shunned units on modern Eng Lit), control of the literary critical scene largely passed into the hands of academics. Some of these clearly were critics of real distinction (see Hoggart, above or David Cecil at Oxford) but others (most notoriously F.R. Leavis operating out of Cambridge) had exclusionary, censorious and politically partisan agendas that poisoned the field of discourse and helped prepare the way for the hysterically PC anti-culture that chokes the intellectual climate today on so many campuses. In a memorial tribute to John Gross, Geoffrey Wheatcroft wrote that The Rise and Fall was Gross’ great “repudiation of the attempted monopoly of literary criticism by ‘the university’ and the larger academic appropriation of our common culture.”

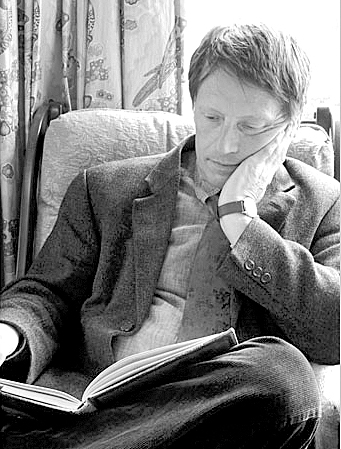

With the rise of the Internet, the horrific pinch being felt by publishers and bookstores everywhere, the atomization of the reading public into disparate cliques and the winnowing of book review space in most newspapers and magazines, I frankly didn’t anticipate that anything was likely to be published soon to supplement that trio of treasures above. So imagine my delighted surprise a couple years ago to read a profile in The Guardian of novelist, literary biographer and critic D.J. Taylor (b: 1960) which concluded: “He then plans an “enormous non-fiction book, which will not earn me much money but I’ve always wanted to write, about English literary culture in the last century. How books are conceived, written, printed, published, reviewed, sold and read.” He describes it as a “continuation and homage” to John Gross’s magisterial The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters. “And it will end with digital culture and me asking whether there will still be book reviews in the future.” |

|

Taylor’s The Prose Factory: Literary Life in England Since 1918 was published this spring and is a sterling – if sobering - addition to this recherché canon. The book shows how at ever shortening intervals through the last hundred years, popular tastes shift, some markets wither while new ones emerge, upending the playing field that a generation of writers has come to rely on so that a whole new approach is required to survive. One such rupture was the chaos wrought by the introduction in 1935 of mass market paperbacks. Yes, unprecedented sales suddenly became possible but the per unit royalty rate was fractionalized and many top notch writers of more limited appeal were dropped from publishers’ lists altogether. But the paperback upheaval was a walk in the park compared to the havoc wreaked by digitization.

Describing some writers’ manoeuvres to keep their heads above water, (and the book is packed with financial details such as royalty rates, annual incomes, and reviewing fees) Taylor recounts tales of the perpetually strapped Hugh Kingsmill (1889-1949) cadging publisher’s advances for books he had no hope – and possibly no intention - of ever writing. A Kingsmill aside when writing about Richard Wagner sponging off Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria could almost serve as The Prose Factory’s leitmotiv: “In their financial aspect the lives of most writers, painters and musicians suggest a man leaping from ice floe to ice floe across a wide and rapid river. A strenuous, not a dignified spectacle.” |