“I didn’t know Jack Chambers or his work at all. I walked into the gallery and was really quite moved by it . . . I liked all the blue sky in the paintings, the feeling he expressed for his community. And that was London." |

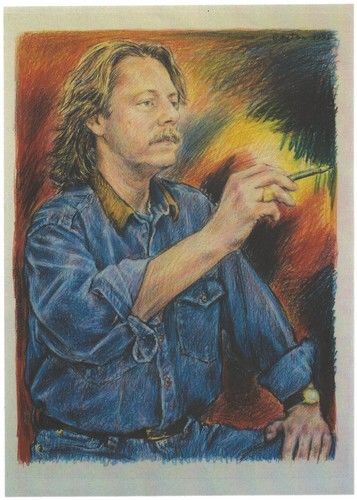

ALAN DAYTON

LONDON'S PORTRAITIST THIS AFTERNOON from 2 to 5 p.m. at Eric and Catherine’s Studio at 105 Clarence Street there will be a tribute for and an exhibition of paintings by London artist Alan Dayton who died this May at the age of 64. It’s taken this long for family and friends to pull together some sort of memorial because they were so completely blindsided by Dayton’s passing. Not even those closest to him knew anything was wrong until very shortly before he died. Dayton may have justified this secrecy as a strategy to spare others anxiety and dread but shocked as his friends were to learn that he had been so seriously ill, the always shy Dayton never did call attention to himself. Indeed, his forte as London’s foremost portraitist was to lavish his attention on others. Born in New York and raised in California, Dayton came north to Canada in 1969 as a draft dodger. After finishing high school and meeting his first wife he had enrolled in English and art at UCLA but bailed out in the middle of his second year, unable to keep up the charade. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life,” he told me in a 1990 interview. “I felt all these pressures. I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. I didn’t want to be in university just so I could keep out of the army. I came up to Canada as an alternative to going into the army or prison or pretending I was psychotic.” The Daytons first settled in Montreal and then the Beaches area of Toronto but were lured to London in 1974 by art, specifically by a Jack Chambers Retrospective that Dayton had seen at the Art Gallery of Ontario. “I didn’t know [Chambers] or his work at all,” Dayton told me. “I walked into the gallery and was really quite moved by it . . . I liked all the blue sky in the paintings, the feeling he expressed for his community. And that was London. I drove over one day to have a look and there were all those trees and the sky – I recognized it all from his paintings.” Dayton then went on to voice one of the most beautiful tributes to London I’ve ever heard: “It felt like the opening of some Fellini film where you get the bird’s eye view of a community and you know that everything you’ll need for a great story is being laid out before you. The frame is small enough that you can take it all in but it’s big enough that you know there’s going to be some surprises – there’s enough scope to allow diversity and movement. London is a great resource for an artist. A greater artist could do even more with less but the human pageant is all here.” A lot of artists shy away from portraiture. This is partly because it can be a bit of a ghetto that doesn’t garner much in the way of critical attention but also because portraits are so notoriously difficult to do well. And if the subject of a portrait isn’t pleased then who else is likely to buy it? “People want a likeness, right?” London artist Kevin Bice said when I asked him to share his thoughts about Dayton. “A single photographic image rarely cuts it. Who’s ever been happy with their school photographs? With portraiture, all it takes is a subtle miscalculation in proportion or nuance and the whole thing goes south. As an artist I really envy anyone like Alan who could keep that sort of focus and find it endlessly absorbing. With my own work I tend to flip around like a grade nine boy at a dance but Alan really had a fascination with portraiture that never seemed to end.” In addition to individual commissions Dayton also developed extensive series on other visual artists, writers, theatre people, and perhaps most tellingly, street people. The very first portrait he ever exhibited was his 1977 painting of Jessie Robbins, a touchstone of Old South London famous for riding her bicycle in all weathers and collecting twigs in her basket carrier. That painting sold quickly at the 37th Western Ontario Exhibition but a more important confirmation of the work’s worth for Dayton was the fact that Jessie haunted the gallery for the duration of the show, proudly standing next to her portrait and chatting with patrons. It was a glorious moment in which both artist and subject felt that they had been validated. Herman Goodden / London Free Press, August 23, 2013 |